DEAUVILLE: THE name conjures up slim, elegant women walking along the wide, weathered boardwalk, one hand holding a parasol, the other restraining a dog at the end of a leash. The parasols are gone now, the glory days passed with the war, yet Deauville perseveres: an immaculate seaside town in France’s Normandy region that is adorned with wonderful seasonal flower arrangements throughout the year.

Les Franciscaines, a renovated convent in the town located five minutes’ walk from both the beach and the hippodrome, is at the heart of Deauville. A building that had lived many lives before becoming a cultural hub for the town, it was here that earlier in the year, the works of one of the great photographers, the Brazilian Sebastião Salgado, were shown.

The building’s layout is deliberately simple, articulated around a large vertical axis and a large horizontal plane, making it easy for visitors to find their way around. The flow of visitors through the interconnected spaces is certainly one of enjoyment, pleasure, discovery and exploration. It is a place where people clearly like to linger. And linger they certainly did with Sebastião Salgado.

If any mystery was wrapped in an enigma, it was and still is Amazonia, but Salgado helped the rest of the world to comprehend what is happening there. His was a culture of encounter, making us confront people and places when we have no idea about their existence at all. He opened our eyes, but in so doing he became a polarising figure. He upended expectations about what photography can do – to become a voice, time and time again – demonstrating a determination to prove that photography was every bit equal to any other art. An aesthete of misery, a master behind the lens, Salgado’s vision of unblemished nature and humanity nevertheless came in for considerable criticism. Discomfort over his representation of the Brazilian jungle, objectification of indigenous people, naked women and children, only made one remember John Stuart Mill, who warned that ‘he who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that’.

The exhibition in Deauville also included an ode to the birth of time, what Salgado called Genesis. This was a major project launched by the photographer in 2004. His wife, Lélia Wanick Salgado, said: ‘Over the next eight years he made 32 trips to the ends of the earth, from the Galapagos to the Amazon rainforest, across Africa and the Arctic. It was a quest to find the origins of the world, a world that evolved for millennia before having to face the pace of modern life… [The photographs he made] of landscapes, animals and peoples are an escape from the contemporary world. They pay tribute to vast, distant regions, pristine and silent, where nature continues to reign in majesty… They pay homage to the fragility of the planet.’

Over two years in planning, the exhibition was curated by Pascal Hoël, and designed, as part of the France-Brazil year in partnership, with the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris, home to France’s most important collection of contemporary photography.

Born in Minas Gerais in Brazil in 1944, Salgado met Lélia when he was 17. He read economics (he had a PhD), she was studying architecture; they were both members of a revolutionary left-wing group until they left the country as political persecution increased under the brutally repressive military dictatorship that ruled Brazil by fear and force for 20 years from 1964. If there is one thing he always believed in, it was the importance and the value of the story – a belief that at times bordered on the magical, or at least the beyond pedestrian – the duty he owed to a story.

Whether it was war and famine across the Sahel where he worked with Médecins Sans Frontières, sharing the lives of people in the Mexican Sierra Madre, cataloguing manual labour from Azerbaijan to Poland, from Bangladesh to Rwanda and Sicily, to open cast mining in Para in Brazil, bearing witness to the upheaval of major movements of landless peasants across the world, he managed somehow to salvage some human dignity from the wrecking ball of history.

All that unbridled passion – the work is so assured and confident – clearly came from a mature, experienced hand. Over the years his consistency was one of the eerie things about him. But that all came at a price. Perhaps it should come as no surprise that at times, a mental and physical reaction to the horror of it all meant that this remarkable man considered giving it all up and becoming a simple farmer.

Living in self-imposed exile in Paris, Salgado was almost 30 before he switched careers to photography, having borrowed Lélia’s camera, some time before she became director of the Magnum Gallery in Paris. His name stands in photojournalism’s pantheon, up there alongside Capa, Cartier-Bresson, Margaret Bourke-White, and Irving Penn. He covered hundreds of assignments in 130 countries, and is a significant part of the history of photojournalism itself. His archive approaches a million images. Salgado worked with the best agencies: Sygma, Gamma and, for 15 years, Magnum, which he left in 1994. Instantly recognisable, black and white images, dramatically lit, his work embodied the power of collective storytelling that Magnum embodies.

A UNICEF goodwill ambassador, Salgado won every prize imaginable, from the Royal Photographic Society’s Centenary Medal to the Légion d’honneur in France; the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Praemium Imperiale, the King of Spain International Journalism Award, the list is endless. For the past 30 years he was working to turn 17,000 acres into a nature reserve as part of the Mata Atlântica, a forest that extends along the Atlantic coast of Brazil. For Salgado, human blindness leads to self-destruction, which was a cause for great pessimism. But nature, he said, continues on its own course and keeps evolving.

Memories are short, and history easily forgotten. Intrepid, brave, driven, the Indiana Jones of the photographic world, Salgado ensured that the indigenous people of Latin America could not be ignored nor would they be forgotten.

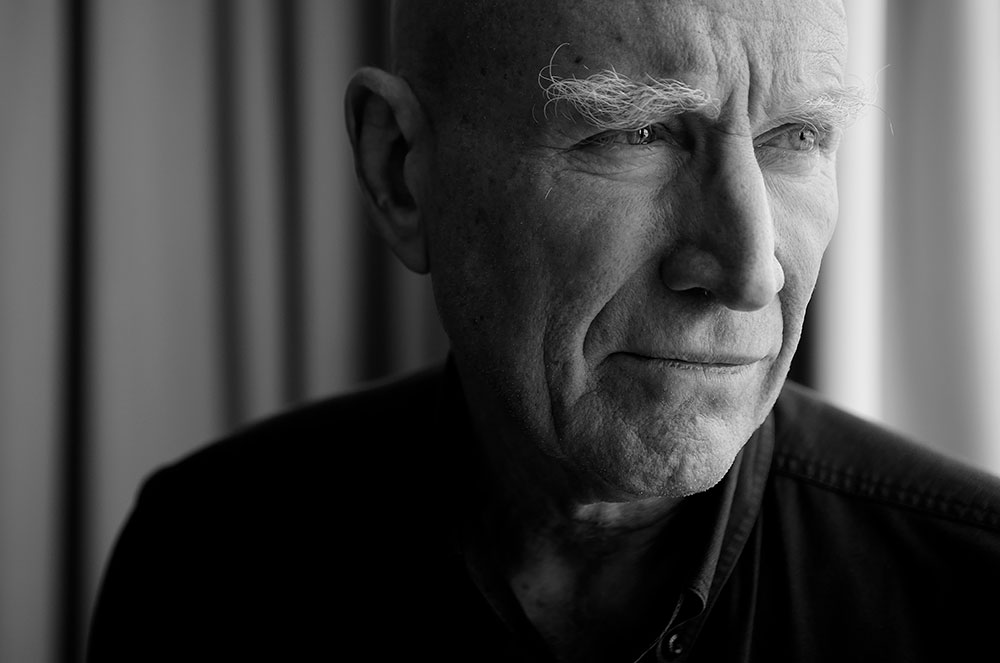

Sebastião Salgado (below) died in May this year. Currently on show at les Franciscaines, and around the town until 4 January 2026 is an exhibition called Planches Contact’ a festival that aims to make Deauville a permanent venue for photography. The event champions young photographers but also includes exhibits of major names like Cindy Sherman and Arno Minniken. A place that has an enduring relationship with images, that has always been a source of inspiration for artists, is today reasserting that spirit of contemporary creativity with a commitment to the future. Salgado would have approved.