ONE OF MY PERSISTENT frustrations in my role is the ugly paraphernalia museums and galleries use to keep people away from paintings and objects. There’s no global consensus on best practice around this. A stanchion favoured by one gallery is considered a trip hazard in another. A subtle textured tape or timber ledge disappears in some spaces but feels clumsy elsewhere and, in a different context, might be thought of as a health and safety issue. Beautiful, evocative sculptures are hidden behind glass or Perspex hoods, while hastily placed signs shout ‘Do not touch’ – all of it interrupting the intimacy between viewer and object or artwork.

We’re currently working on a number of projects in India, and, during a recent site visit to Kolkata, I was struck by a radically different philosophy, which is one of return and impermanence. Skilled artisans spend months crafting detailed sculptures from bamboo, straw and clay that they collect from the river at the end of the road. Then, during Durga Puja, these idols are immersed in the river or burned, completing a cycle of creation and dissolution. The idea that objects live and die, returning to earth or water, felt deeply moving, especially given my life’s work preserving objects behind barriers.

Nearby, a different tradition is evident: tea is served in unfired terracotta cups, called bhar or kulhad, which are smashed and returned to the earth after use. These disposable, biodegradable vessels embody a profound acceptance of impermanence and connection to the natural cycle. They feel humble and fleeting, yet they carry an unexpected weight, evidence of a culture that knows how to let go.

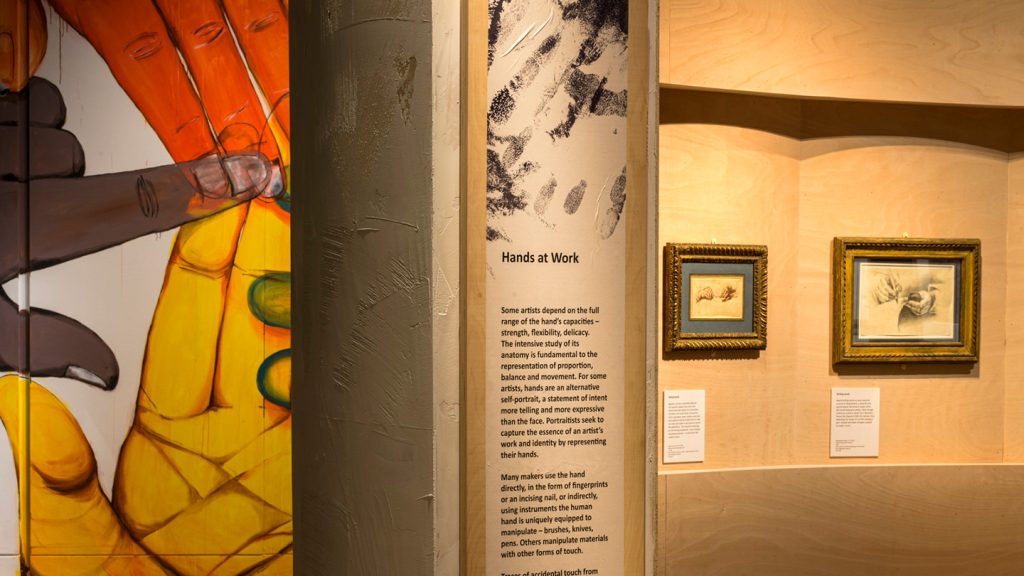

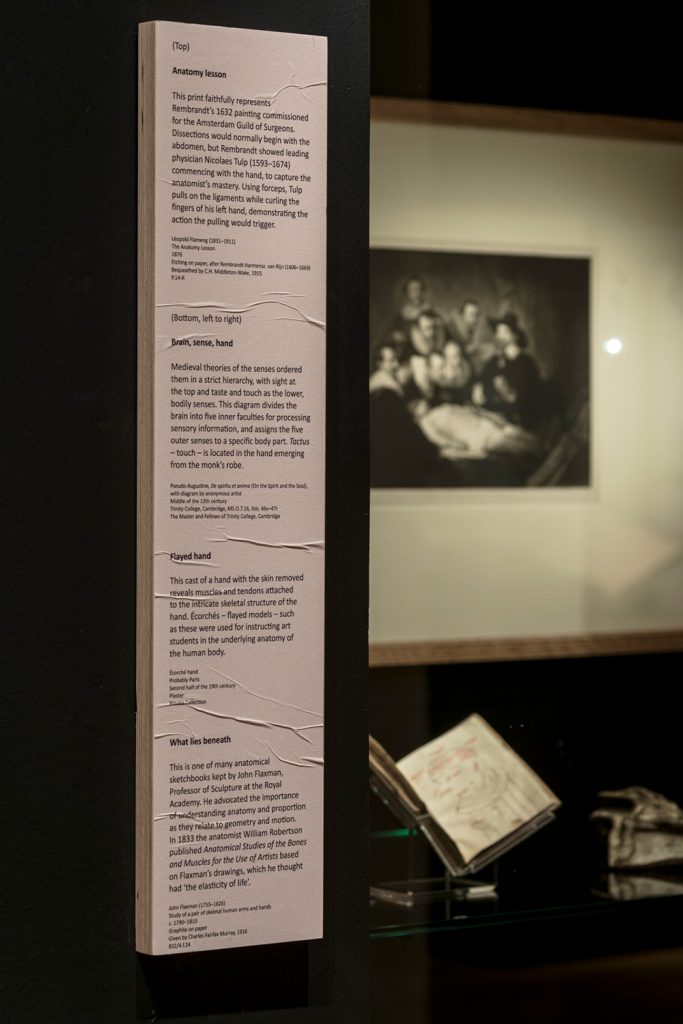

This philosophy was echoed in an exhibition called The Human Touch: Making Art, Leaving Traces, which we designed for The Fitzwilliam Museum during the pandemic. The museum team explored objects and artworks around themes to do with touch, and our response was to look at how we could stimulate the senses in the ways in which they were displayed. We made films using macro lenses that revealed hidden sensory moments in the artworks – almost replacing touch with a visual experience. For example, exploring Rodin’s fingerprints, capturing the artist’s physical touch with almost forensic intimacy.

Some religious statues bore centuries of human contact, worn smooth in places while untouched in others. We embraced these imperfections in the exhibition design itself, using crinkled text pasted on walls, rough timber construction, visible joins. These marks of time and craft became meaningful, not distractions. They were part of the story.

Of course, it isn’t practical or responsible to leave priceless objects unprotected. Many have survived centuries and require care. But what if we approached this more holistically? Could we mix things up and disrupt the barriers, make all artworks visible behind nearly invisible non-reflective glass? Could we create spaces where boundaries dissolve and where visitors know everything is touchable, accepting that change will follow? Might we trust that people, when offered closeness, will respond with care?

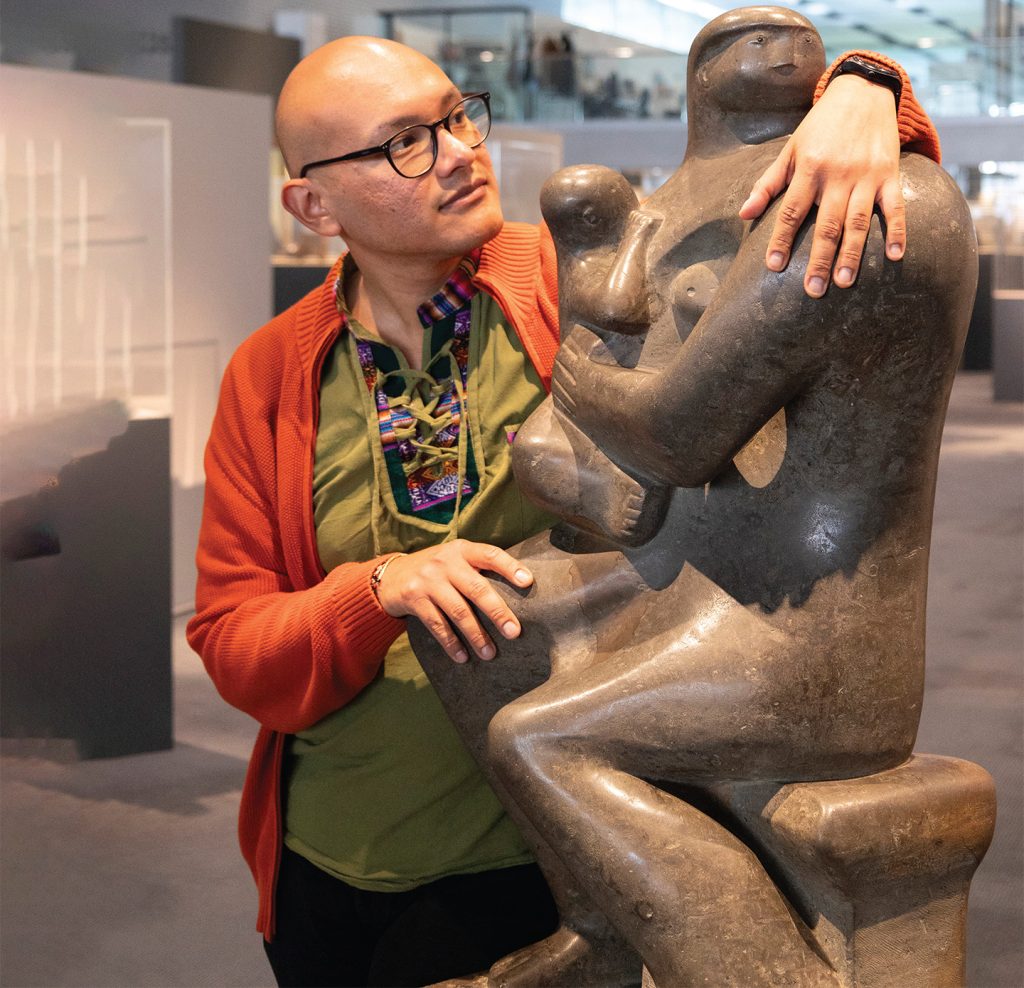

The Sainsbury Centre in Norwich embodies this philosophy, where they are experimenting with treating artworks as living entities rather than untouchable relics, inviting visitors into deeper, sometimes physical encounters. With Henry Moore’s Mother and Child sculpture, for instance, visitors are invited to hug it. The museum questions whether the life cycle of artworks should be artificially preserved, or whether objects, just like us, should be allowed to age, wear and die.

People have been thinking about this for decades. Nina Simon’s The Participatory Museum advocates transforming museums from passive repositories into active spaces where visitors contribute, interact, and co-create meaning. This model challenges the sterile ‘Look but don’t touch’ dynamic, making museums vibrant cultural hubs. It acknowledges that meaning doesn’t reside solely in the object, but in the relationship between the object and the person encountering it.

At the newly opened V&A East, it’s quietly thrilling to stand beside objects that feel almost unguarded, unmediated by ropes or thick glass. There’s a generosity at play here, a willingness to trust the visitor. The curatorial approach seems to recognise that proximity cultivates rather than diminishes respect; that when we’re granted the power to touch, we often choose not to. In a recent Frieze article, Tim Reeve, deputy director of the V&A, spoke about purposefully revealing the hidden mechanisms of the museum, letting backstage become front-of-house, embracing a museum embedded in the life of the city. His words felt like a rallying cry: an invitation to museums everywhere to think more boldly, break down inherited conventions, and reconsider what openness really looks like. The ability to summon objects, to study them in close quarters, shifts agency back to the viewer. It builds intimacy and it says that you belong here. It almost feels as if the building is being shaped by the visitors.

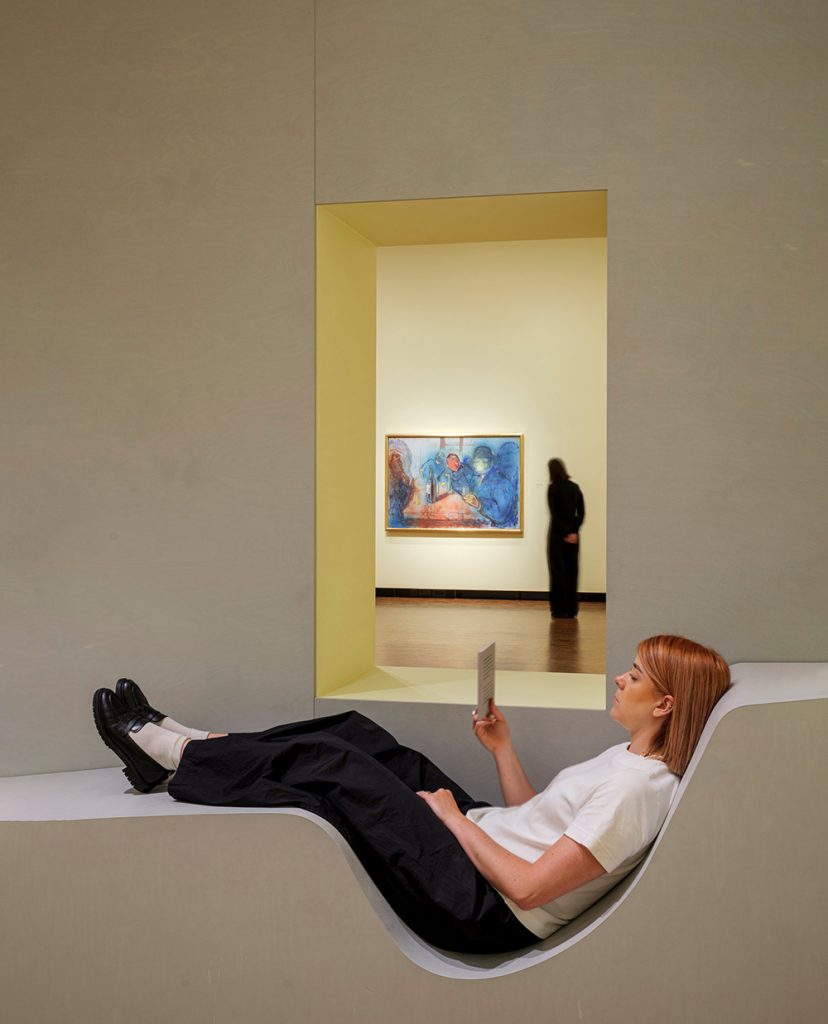

We are also in our work trying to find ways in which we can disarm the visitor to challenge their physical relationship with the works. In Lifeblood at the Munch museum in Oslo – an exhibition about medicine, caregiving and the changes that this went through within Munch’s lifetime – we created furniture that positions the visitor in different ways, whether upright, supported and close-up to the works, or lying in a protective curve reflecting on the objects and artworks. This journey supports and transforms us out of the gallery into a more intimate environment.

So, where do we go from here? Is there a future in which care and closeness coexist and where museums safeguard without ruining the experience, where objects are held tenderly but not separately? Through clever layering, non-reflective glass, sensory design, and material honesty, perhaps we can build spaces that breathe and where connection doesn’t require detachment? Where some things are protected, but others are sacrificial, designed to be touched, altered, weathered by human hands. Where the patina of time becomes part of the object’s story. Maybe we commission new objects that are born to be held, to be worn down. Maybe we soften the edges between viewer and collection, between permanence and decay. We might not be able to immerse our treasures in the river, as they do in Kolkata, but perhaps we can loosen our grip a little. Create room for touch, for risk, for feeling. Let our museums become places not just of preservation, but of presence, spaces where people come not just to look, but to connect, to remember, and to let go

Pippa Nissen is a director and founder of Nissen Richards Studio, winners of over 50 creative awards for the practice’s prestigious, international portfolio of exhibition design and architectural projects