COUNTRY PROFILE: BENIN

Capital Porto-Novo

Area 114,763km2

Population 13.7 million

Languages: French, also Fon, Yom, Yoruba, Gun, Baatonum, Biali, Dendi, Fulfulde

Life expectancy 60 years (men) 63 years (women)

BENIN – A FAR-OFF COUNTRY of which we know little. That is about to change. With a new National Assembly under construction designed by a Pritzker-winning architect, four new major museums, and four sensational artists on show at the Venice Biennale, where for the first time Benin had a pavilion, the country’s vibrant artistic scene, its cultural heritage and design talent will become far better known to everyone.

Formerly part of French West Africa, when it was known as Dahomey, Benin is a wedge of land located between Togo, Nigeria, Niger, and Burkina Faso. The country’s two main cities are both on the coastal strip: the capital, Porto-Novo, and the seat of government in Cotonou, originally developed as a port for the transatlantic slave trade by the Portuguese. The country gained its independence in 1960.

Western European overseas expansion was exploitative, extractive and racist. Benin suffered. The slow acknowledgment by Europe of the realities of those empires and its deep and continuing impact on culture and institutions has hardly begun. Since Benin gained independence there have been coups and regime changes, and changes of constitution and governmental system: tribal, Marxist, nationalist, socialist, co-operative, liberal. At times, the unacceptable was replaced by the unpalatable. In the past decade, things have calmed down.

Benin’s participation in the Venice Biennale in 2024 marked a crucial step in an ambitious government programme that has been underway since 2016. The aim is nothing less than the structural transformation of the economy by making unprecedented investments in support of culture, the arts, and creative industries, focusing primarily on five areas: cinema, the performing arts (dance, music, theatre and performance), the visual arts, heritage and publishing, intending to establish Benin as a pivotal centre for the creation and dissemination of art on a regional, continental and international level.

Two museums are being rehabilitated, while four are currently in architectural planning: the Musée d’Art Contemporain de Cotonou, the flagship of the new cultural quartier; the Musée des Rois et des Amazones du Danxomè, which will accommodate 26 royal treasures that France returned in 2022, a century after they were looted by colonial forces; the Maison de la Mémoire et de l’Esclavage within the former Portuguese fort, an 18th-century historical monument at the heart of the Ouidah Museum of History; and lastly the Musée International du Vodun, a flagship museum in the city of Porto-Novo intended to rehabilitate the image of a muchmaligned and globally poorly understood indigenous religion, Voodoo. This will make culture second only to agriculture in its contribution to the country’s economy. That also means considerable investment in arts education, with a new Africa Design School campus located in Ouidah with links to L’École de Design Nantes Atlantique, plus a significant boost for the École du Patrimoine Africain, which trains heritage professionals, work that has gained greater relevance since Benin and other African countries have begun to recover looted treasures from European museums. Such publicly funded, government-led major museum projects that Benin is undertaking have little precedent in Africa. Taken all together it means that Benin will be one of the very few countries in Africa that put arts and culture at the heart of policy.

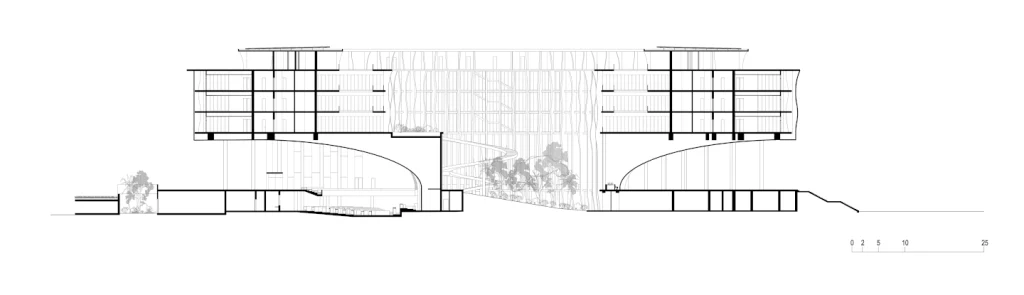

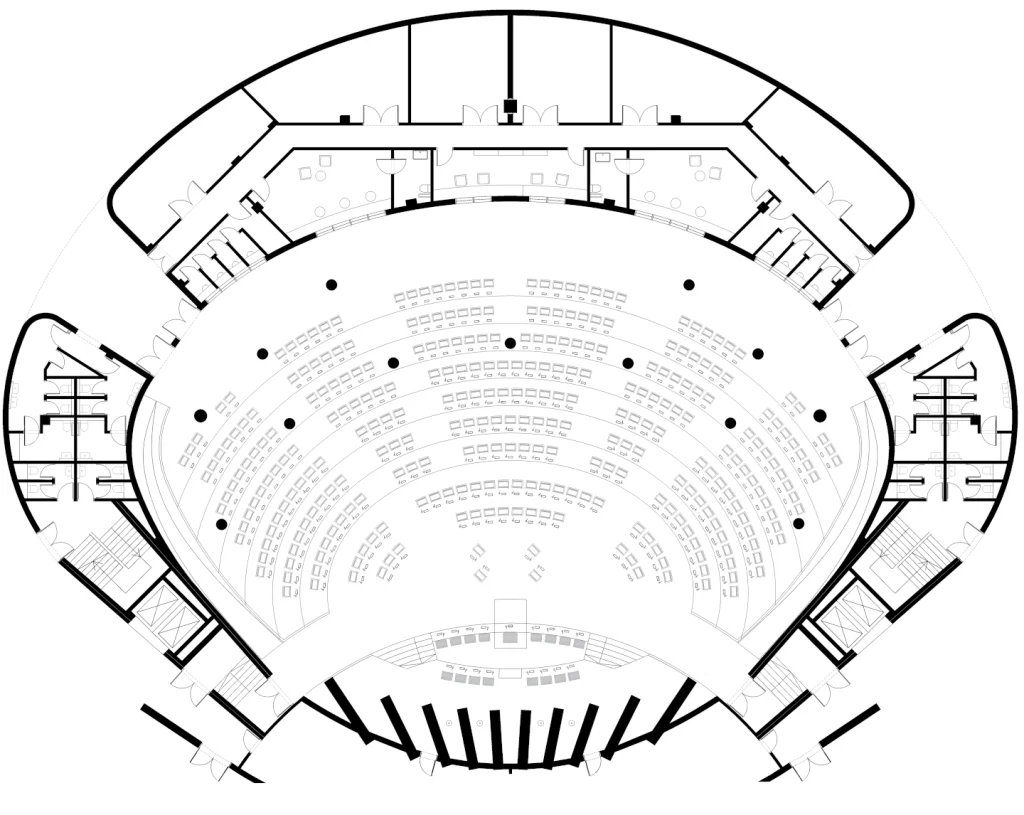

The new National Assembly has been under construction since March 2021 and is due for completion this year. It has been designed by Francis Kéré, an internationally renowned Burkinabè architect, one of the profession’s biggest stars of recent years, a singular beacon in architecture. A former winner of the Aga Khan Award, he has since won the Pritzker Prize in 2022, the Praemium Imperiale in 2023, and in 2024 the 30th Crystal Award of the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos. The projects of his firm, now based in Berlin, range from the Cultural Oasis Agricultural Institute in Saudi Arabia, to the joint UNESCO-Interpol innovative project to create the first virtual museum of stolen cultural artefacts, to the Serpentine Pavilion in 2017, and the future Las Vegas Museum of Art, to be built in the city’s growing cultural district Symphony Park. Known for his resource-light community buildings – on social initiatives for marginalised communities using local vernacular forms re-contextualised within contemporary design – the firm has designed a number of remarkable schools and colleges, housing projects and health buildings. A multi-use civic centre at the heart of the Technical University of Munich’s Garching research campus is in design, along with a proposal for a new National Assembly building in Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso. But it is the Benin National Assembly that will probably create the greatest buzz when it is completed.

Innovative buildings are often, unsurprisingly, small, functionally undemanding pavilions or pavilion-like structures, and the history of architectural styles is often best illustrated from their small beginnings. The Serpentine pavilion signalled the way for the National Assembly building in Benin. Taking inspiration from the palaver tree – the age-old African tradition of meeting under a tree to make consensual decisions in the interests of the community, a timeless symbol, having borne witness to previous generations and inspiring respect for the majestic forces of nature – this was where the concept for the new National Assembly began.

In 2023, the Venice Architecture Biennale was pointedly political. Africa was the star. In the radically white world of architecture, so structurally dominated by Western thought, this was something of a shock. The curator, the remarkable Ghanaian-Scottish architect Lesley Lokko, who received the RIBA Gold Medal this year and is a revolutionary force in her own right, said that through slave labour and colonial expansion Western powers had built empires whose impossible architecture, often neoclassical in style while claiming to represent universal values, was itself an expression of political control. Since then there has been the exhibition of Tropical Modernism at the V&A that displayed how Britain exported an architectural style to West Africa and India, the legacy of which is as complex as its origins. The show demonstrated how it was both progressive and patrician, ignoring local traditions, at the centre of which were the British architects Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry, who apparently treated the world’s tropical regions as interchangeable in their architectural needs, regardless of cultural differences. That sums up the importance of both Venice Biennales, for architecture in 2023 and art in 2024. And especially in the case of Benin. The country is in a period of artistic renaissance with that revitalisation of its museum infrastructure leading the way to present a confident new face to the world.

Franck Houndégla designed the Benin Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2024. The artists exhibiting were Chloé Quenum, Moufouli Bello, Ishola Akpo and Romuald Hazoumè, and the show was curated by Azu Nwagbogu, alongside Yassine Lassissi, director of visual arts at the country’s Agence de Développement des Arts et de la Culture. Bello’s work explored the desires and limitations of women in Beninese society; Akpo’s was an ‘archaeological excavation of history’; Quenum reflected the ‘fragility of diaspora’, while the established figure of Hazoumè, a prize-winning artist with a history of exhibitions in the UK, France and the US, used recycled materials, ‘the refuse of consumer society’, to create his works, including black plastic jerry cans, ubiquitous in Benin for transporting black market petrol from Nigeria, cans that he uses as a potent metaphor for all forms of slavery, past and present, drawing parallels with the container’s role as a crucial, faceless unit within commercial systems, dangerously worked to breaking point before being discarded. In Venice he fashioned a magnificent ceremonial hut out of the old cans.

Nwagbogu explained that it was essential the pavilion felt like ‘one big exhibition’, rather than four separate presentations. The artists talked of their works being ‘in conversation’ with another. A trailblazer engaged with issues of decolonisation, restitution and repatriation, Nwagbogu was named by National Geographic its ‘explorer at large’ for the society. The exhibits’ theme was ‘everything precious is fragile’. In 1889, Goethe coined the phrase ‘see Venice and die’. And that in a place where climate change laps at every canal-side palazzo and vaporetto stop. Today, artists delighting in the Biennale’s eminence might now have their own adage: ‘exhibit in Venice and shine’. These Beninese artists did that. They shone a new light on Venice.

Venice: a city of casual encounters and chance recognitions. Amid the hazy light and shifting waters of the lagoon in 2024 nothing was what it seemed. So much of the Venice Biennale is self-referencing – what was here before, how does it compare with the last show or another show, one of the 100 or more biennales that now exist around the world. Dissent, diplomacy and drama have always surrounded the Venice Biennale. They used to call this waterlogged city the Most Serene Republic, but there was nothing serenissima about this Biennale: it was as political as ever with both the Ukraine/ Russia and Israel/Gaza conflicts hovering over everything. Artists are hardly synonymous with nations, nevertheless the wild, the weird and the controversial exhibits were confronted with political protests that were impossible to ignore.

Yet as ever, the Venice Biennale is not just food for thought, it’s a feast; and one that every nation hopes to gain from, simply by being there. There were a number that aspire to be an artistic and cultural hub of Africa: Ethiopia, Nigeria, Senegal and Tanzania. Benin was a new one, but a significant one. Amid those swirling waters and that hazy light, it was just possible to discern which country could be the eventual, and surprising, winner. There is a seldom seen Sondheim musical, Merrily We Roll Along, that contains the lyric, ‘but for those who dare / the world is there / to change’. This year Benin has dared.