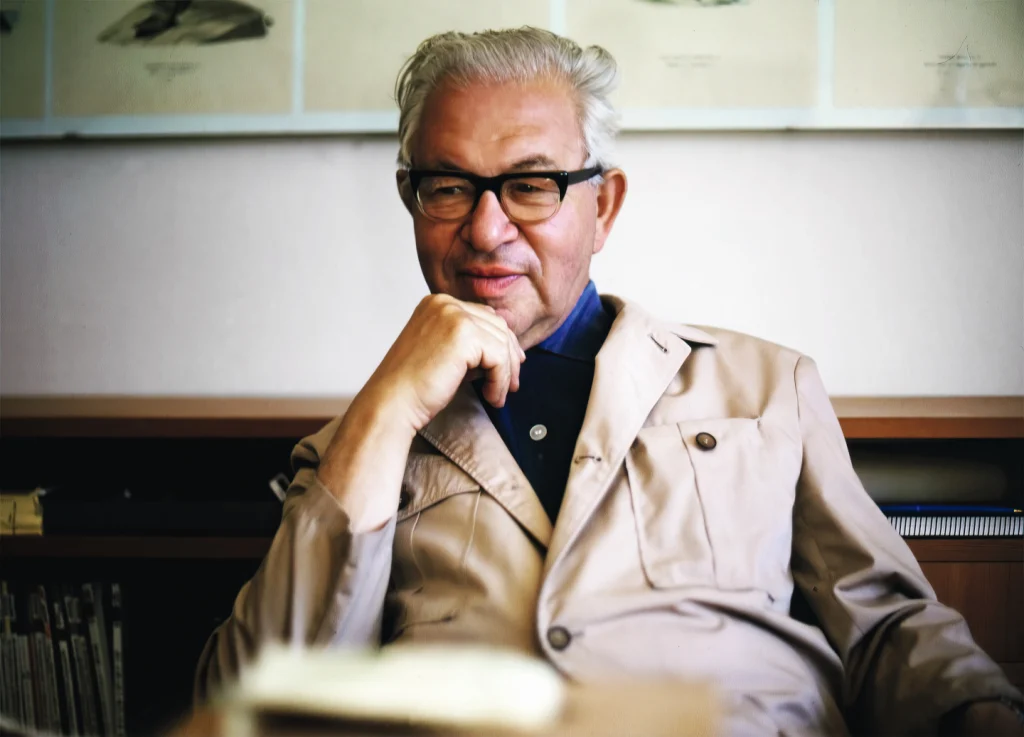

IN DENMARK, Arne Jacobsen (1902–1971) is remembered as one of the 20th century’s most influential and respected architects.

On the international stage, however, it is his furniture designs that most likely spring to mind when his name is mentioned. His Egg, Swan and Series 7 chairs, for instance, are icons of modern design and remain bestsellers to this day. But he was far more than an architect who also happened to design furniture. As Thomas Dickson and Henrik Lund-Larsen write in the sumptuous new book The Designs of Arne Jacobsen (Prestel), not only was he ‘one of the most farreaching and productive innovators of his generation’, but a ‘dedicated creator who may be one of Denmark’s first true industrial designer’. Their richly illustrated and rigorously researched volume traces the remarkable trajectory of Jacobsen’s career as a designer, from his early experiments with functionalism, to his most celebrated modern designs and lesser-known gems, such as his many textile designs.

Jacobsen believed in ‘total design’, conceiving and creating every aspect of a building himself, from its architecture to its fittings, fixtures, textiles, lighting and furniture. His clean, functional aesthetic and material restraint produced a number of celebrated Danish buildings, including the SAS Royal Hotel (1960), the magnificent town halls of Aarhus (1941), Søllerød (1942) and Rødovre (1956), and Munkegård school. He also left his mark in Britain with the brutalist Saint Catherine’s College (1966) in Oxford and the space age-like Royal Danish Embassy (1977) in London. Over four decades he designed 400 buildings, 150 textile patterns, 100 furniture designs and ten major product collections. Yet despite his commitment to innovative design, he saw himself primarily as an architect. As the book’s authors note, he loathed the word designer, considering it ‘an English buzzword’.

Jacobsen grew up in the Østerbro district of Copenhagen, though from the fifth grade he attended boarding school in the town of Nærum. It was here that his talent for drawing and painting was discovered and his desire to pursue architecture subsequently led him in 1924 to the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts’ School of Architecture, where his training rested on a solid classical foundation. But Jacobsen was a talented and enterprising architect who intuitively understood where architecture was headed. After a few years working for the city architect in Copenhagen, he established an independent practice. By 1930 he had already designed several villas and other residential developments, including his own strikingly modern, functionalist house in Ordrup – a sleek, flat-roofed building that appeared to be made of white concrete but was, in fact, plastered brickwork.

Despite Jacobsen’s penchant for the functionalism pioneered by Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, his early clients preferred less radical ideas, and so villas in yellow and red stone with gabled roofs became his signature style in the municipality of Gentofte. He later landed commissions for multi-storey buildings and began entering competitions, often in collaboration with Flemming Lassen and Erik Møller. With Møller he secured the commission for Aarhus City Hall in 1937, and with Lassen the commission for Søllerød Town Hall in 1939. Both projects were built simultaneously and reflect a more subdued, Nordic version of modernism, one quite detached from Jacobsen’s ultra-modern post-war designs. Indeed, Aarhus employs a refined, almost classical aesthetic with spacious halls, long corridors and elegantly curved staircases. As the many photographs in the book show, the interior is striking for its consistent use of wooden slat wall coverings, wall lamps and hexagonal pendant lights. Wood is the dominant element here, a theme continued by the stylish furniture, all of which was designed specifically for the building.

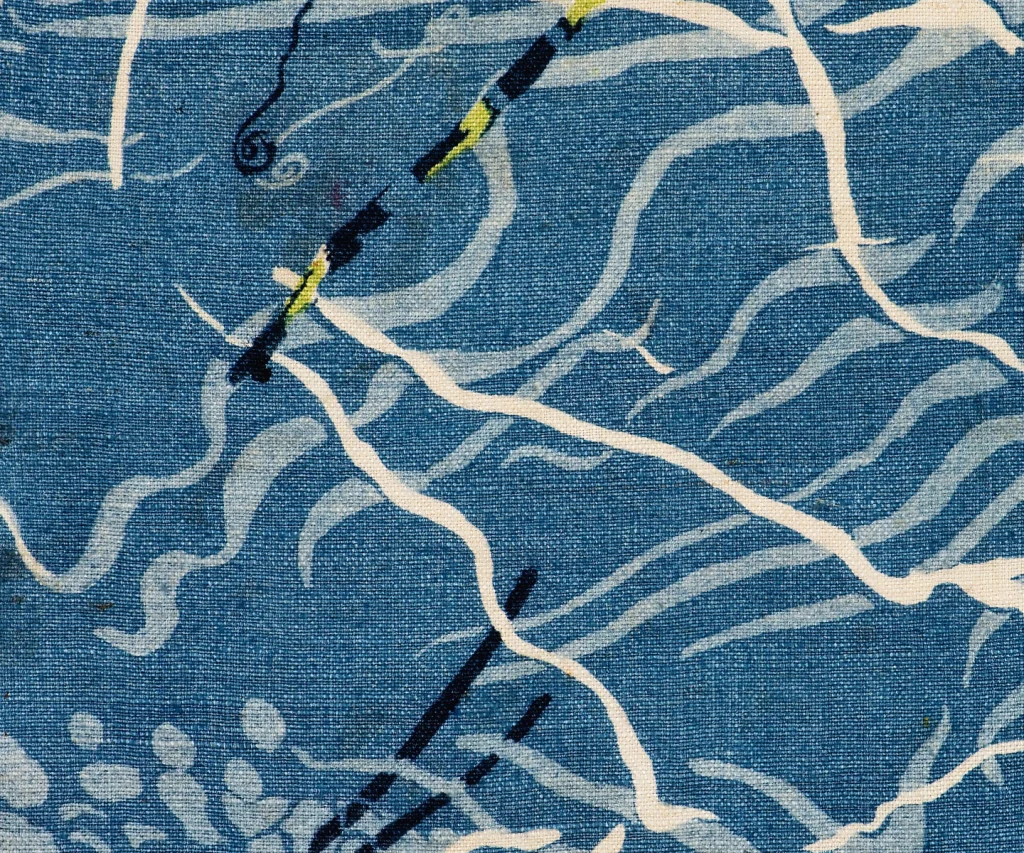

In April 1940, the Nazis invaded Denmark. Jacobsen went underground and, though he sought to downplay his Jewish heritage, he was eventually forced to f lee the country in 1943, escaping to Sweden in a rowing boat in a daring 15km journey across the Øresund Strait. Thankfully, he was accompanied by the elite rower Herbert Marcus, along with Poul Henningsen and his future second wife Jonna Møller. While in Stockholm he engaged his longstanding interest in botany, and Dickson and Lund- Larsen discovered many of his plant studies and watercolours in the Danish Art Library archives. Botany, they write, gave Jacobsen a freedom to explore new possibilities and ‘a foundation of an expression that would later emerge in the form of design and buildings’. But it was in the large collection of textile patterns that he designed with his wife Jonna for the Swedish department store Nordiska Kompaniet that his infatuation with the natural world is most clearly seen. Jonna had trained as a textile printer and, working together, the couple created patterns featuring motifs derived from wildflowers. Vegetation (1944) is a lush tangle of green plant forms set against a white background, while the charming Anemone (1944) features an array of the titular flowers in white, yellow and blue. Such designs were made into curtains, dresses, scarves, furniture covers, and even parasols.

Sparked by exile and his relationship with Jonna, Jacobsen’s fascination with textiles continued to grow. Over the next 25 years, the couple created more than 150 patterns, many of which are illustrated in the book, including the striking Lemons in Net (1948), created for Textil Lassen, and the abstract Duck (1956) for Cotil. With good reason, Dickson and Lund-Larsen see a strong link between Jacobsen’s abstract textile designs and his architecture, identifying in his later sketches for houses ‘a change in style with buildings that have a repetitive pattern, inside and out’. It is quite possible, they suggest, that his own house, one of the Søholm Row terraces near Klampenborg, grew out of his textile designs. Constructed in yellow brick with eternit roofing, these homes display repeating patterns not unlike those in his and Jonna’s geometric patterns. In 1950, the couple moved into the end terrace, where Jacobsen established his design studio in the building’s basement.

Commissions for buildings virtually dried up during the war, especially larger public sector projects. However, in the 1950s, Jacobsen, who now enjoyed a good income from his mass-produced textiles, was able to rebuild his architectural practice. It was a period that also saw the creation of some of his most revered furniture designs, which brought him to the attention of an international audience. The time of finely crafted, unique furniture was ending as mass production techniques slowly took over. ‘It was out with woodworking benches and highly specialised carpenters, and in with uniformity and volume, alongside sexy shapes in a new aesthetic,’ write Dickson and Lund-Larsen. Jacobsen embraced this new age and, in 1952, he collaborated with Fritz Hansen on an innovative three-legged chair formed from a single piece of plywood mounted on a frame of tubular steel. Originally called the 3100, it would become known as the Ant.

The instantly recognisable Ant was developed for the canteen of the Novo pharmaceutical company. Departing from Jacobsen’s earlier work, its modern approach to form and material laid a strong foundation for the future evolution of his furniture. Its steel legs followed the precedent set by Charles Eames’s LCW Chair (1945), while its bent plywood seat built on lamination techniques developed for Peter Hvidt and Orla Mølgaard-Nielsen’s AX Chair (1950). Its nickname comes mostly from the shape of the seat shell with its rounded curves and characteristic waist, but also its three thin legs. Although Jacobsen had left the work of his predecessors far behind with the Ant, it was prone to tipping and some people, worried it would collapse, even refused to sit on it. Several new lightweight variants were subsequently developed with Hansen in 1955, including the more stable four-legged Series 7, the Tongue and the Mosquito. The latter of these had a wingshaped backrest, which was easier to handle. The design was ideal for children, and smaller versions were created for one of Jacobsen’s first municipal school buildings, Munkegård in Gentoffe, where it was accompanied by matching desks.

One of Jacobsen’s principle works of total design was the SAS Royal Hotel in Copenhagen, a curtainwall building renowned for its precise, minimalist architecture, glass façades and ultra-modern furnishings using new industrial materials and technology. Dickson and Lund-Larsen provide numerous insights into the iconic furniture found within the building’s guest rooms and other spaces, including the unforgettable Egg chair (1958), which fused seat, back and armrests into a unified whole. Other designs from the SAS hotel include the refined foam-covered and upholstered lounge chair Swan; the teardropshaped dressing table chair Drop (1958); the polystyrene and tubular steel Pot, which graced the hotel’s elegant orchid garden; the lesser-known Giraffe, a curious ‘bastard of a chair’ with a polystyrene shell upholstered in light green and lined with strips of wood along its front edge; and the AJ Lamp (1957), which, with its cylindrical housing and funnel-shaped shade, struck an angular contrast to the organic shapes of the chairs.

The organic design language used for Jacobsen’s popular shell chairs was successfully applied to door handles, candlesticks, salt and pepper shakers, and drinking glasses. ‘Once you find a winning formula, you must use it,’ write Dickson and Lund-Larsen of Jacobsen’s design philosophy at this time. However, his unconventional stainless steel AJA Cutlery was poorly received by hotel visitors who complained that ‘you couldn’t get a pea up to your mouth using the fork’. The cutlery was later used for the professors’ high table in St Catherine’s College in Oxford, the first of Jacobsen’s major building projects following the Royal Hotel. Whereas the hotel’s designs had been characterised by innovation, plastic and organic forms, the prestigious Oxford college was ‘tempered by older virtues’ with wood playing a major role, notably in the Oxford chair, a very formal, high-backed chair made with laminated veneer and intended for the dining room.

The 1960s saw Jacobsen continue to innovate, with lamps for Louis Poulsen, new furniture for Fritz Hansen, and the tabletop series Cylinda Line (1967) for Stelton. Made from stainless steel and with shapes based on cylindrical steel tubes, Cylinda Line offered a modern and functional alternative to traditional silverware and included jugs, coffeepots, cocktail shakers and ashtrays. Cylindrical shapes were again employed for Vola (1969), an innovative series of mixer taps and accessories for the National Bank of Denmark (1971), the last of Jacobsen’s major domestic building projects. With all of its mechanical parts hidden leaving only the handles and single spout exposed, Vola was an entirely new concept. It led to further plumbing fixtures, including a sanitary ware series for Ideal Standard, which included a toilet, bidet and washbasin that employed the same sculptural design language. However, with Jacobsen’s unexpected death in 1971, the project never came to fruition.

As Dickson and Lund-Larsen demonstrate so well, Jacobsen’s innovations showed no signs of slowing in the final decade of his life as his studio became one of Denmark’s largest, growing from his modest Klampenborg basement to a huge villa in Hellerup. In the year before his death, he worked on Kubeflex, one of three flexible stock house projects designed for the prefab manufacturer N. S. Høm. These were essentially modular wooden cubes made of glulam timber, which could be adapted to allow everything from family homes to kindergartens and even larger buildings, all configured from the same elements. The Kubeflex test houses, which featured Jacobsen’s Vola kitchen and bathroom fittings, and which were furnished with his own designs, stand as another example of total design, albeit on a smaller scale than his principal architectural projects. They were completed a few months after his death, but never put into production.

For those only familiar with Jacobsen’s furniture designs, Dickson and Lund- Larsen’s comprehensive study, which covers so much of his rich and varied practice, will be a revelation. Across its 300 pages, there emerges a fascinating portrait of a man who perceived the spirit of the times and adapted his design language and architectural style to suit the era. We also learn of his friendships with fellow designers, the creative circles he operated in and how these helped to shape his pioneering work and timeless designs. Page after page we see examples of his clean, functional aesthetic, which came to define modern Scandinavian design and has left a legacy that continues to inspire designers across the world. As the authors write, he was ‘an artist who intuitively understood what so many needed and craved’.

The Designs of Arne Jacobsen by Thomas Dickson and Henrik Lund-Larsen is published by Prestel, price £55.