IT WAS BACK in the 1950s when – suddenly – along came sophisticated interior designs for high-rise offices in Manhattan, specifically on 6th Avenue in New York and the 48 storeys at number 1271. Designed by the Rockefeller family’s architects, Harrison & Abramowitz & Harris, the Time & Life Building, with its 30 elevators, opened in 1959, two streets over from the Madison Avenue that was synonymous with the advertising industry.

Home to Time magazine, then one of the most successful magazines in the world, it became the setting for Mad Men, the drama about everyone’s favourite mid-century television ad agency, Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce. The interior raised everyone’s sights, blazed new trails, and was produced with a strict discipline; the client was prepared to tolerate genius when he saw it.

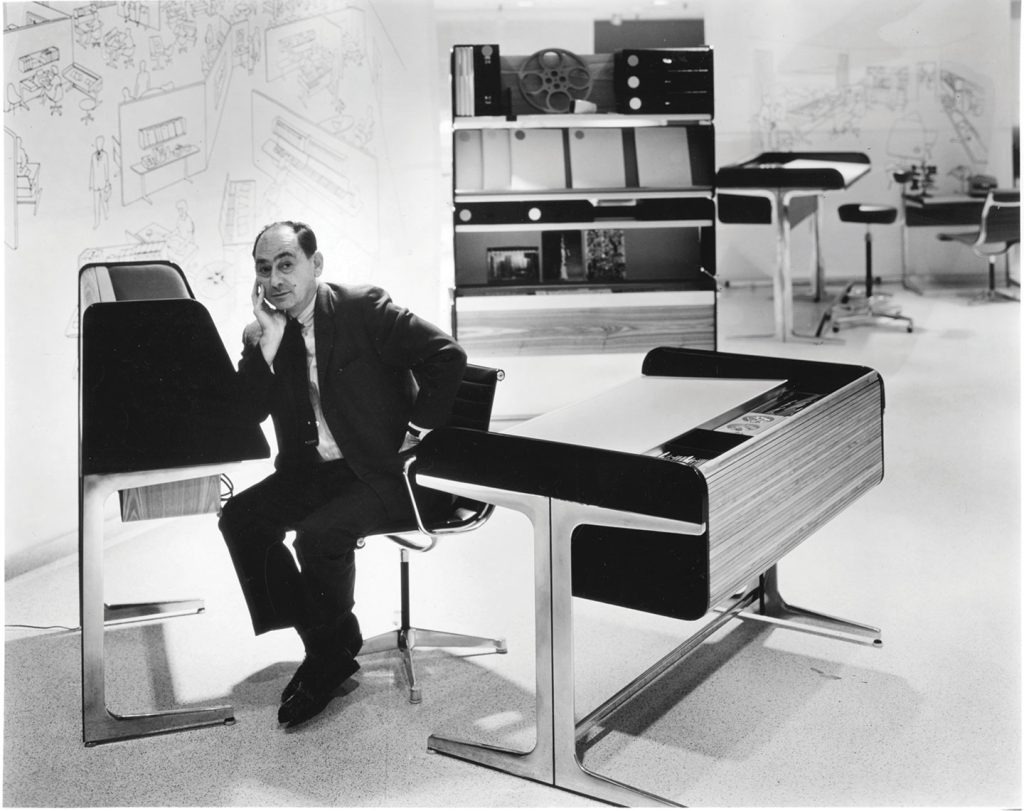

Gerald Luss was that genius. Six decades later and hardly anything seen there today can match the sleek, ambitious style that defined the place, the people who worked there, and the people who made it.

Meanwhile, over on Park Avenue, the 1950s was a time when the international style had its moment in the sun. New York had reinvented itself, setting the standard for office buildings to follow. This was to be the future. A series of tall, conspicuous, highly disciplined buildings were being completed, with uniform grids, structural clarity and great technical excellence. Lever House, designed by Natalie de Blois at SOM with a little help from Gordon Bunshaft, opened in 1952, with the Union Carbide Building and the Pepsi-Cola Building designed by the same team opening in 1960. The Pepsi building was perhaps the ultimate in refinement of proportion and elegance of materials in the cladding of its steel frame, but all three typified a weightlessness in style, whereas the Seagram Building, that was being built at the same time as the Time & Life Building and opened just a few months earlier, was deliberately perceptible solidity.

They all marked the beginning of a new architectural era – curtain wall oneupmanship, skyscrapers as superlatives – that rethought the future of building, defining a corporate aesthetic and establishing an office typology for decades to come, created by architects from the outside in. Designed for maximum efficiency rather than maximum rentability, the building was an advertisement in itself. Yet the modernity of these buildings was not matched by the interiors – witness the executive suites where senior management sat walled in by rosewood panelling, everything signalling solidity, power and wealth: tradition. Far less elegant than any of these, it was the Time & Life Building that had an interior that changed space planning and interior design for a very long time.

Luss was the master of mid-century modern interior design. He set the tone for post-war office style. He brought order by introducing a three by four grid to divide the floors (derived from the PSFS Building in Philadelphia), each section serviced by electricity, fire control and lighting.

Lightweight walls could be easily reconfigured. Hyper-rationalist, it was by no means a cage. Luss designed the layouts, the desks, the chairs and other furnishings: they were all lightweight, easy to clean, and easy to move around. He chose bright colours and good fabrics.

Help was on hand: Alexander Girard, ‘Sandro’, created fabrics for the furniture; Giovanni ‘Gio’ Ponti was responsible for the auditorium, dining and reception areas; and William Tabler, who was to become a hotel specialist, all played their part.

George Nelson designed a rooftop private club and restaurant. Charles Eames designed the Time-Life chair as a favour to his friend Henry Luce, the founder of Time and Life magazines. (It became the Cadillac Eldorado of desk chairs, and the top of the line at Herman Miller, significantly wider than the seat of the Aeron. Modelled after a wider stationary chair produced for the lobby it is still being manufactured today.) Josef Albers, Fritz Glarner and Francis Brennan designed murals for lobby walls. There was a photo gallery on the 28th floor where the photojournalist Alfred Eisenstaedt worked. Luss was responsible for 21 floors of offices. They were all about style and adaptability.

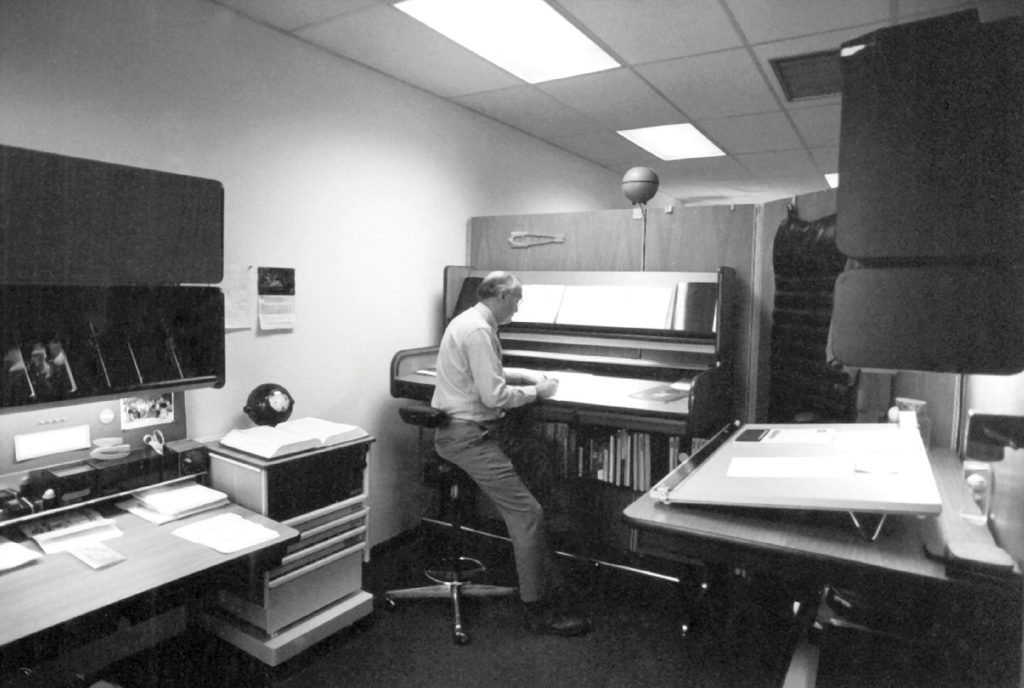

The cliché of ‘a wake-up call’ has earned the witty riposte that one can wake up but still not get out of bed. But these interiors caused others to not merely wake up but leap out of bed, down a double espresso, and be raring to answer history’s summons – welcome news in an industry that often resists change. At the same time as the Time & Life revolutionary interior was being created, the academic Robert Propst was undertaking research as part of the design process at Herman Miller. Propst was an academic discovered by ‘Jan’ DePree, the founder and president of the company. Published in 1968 and a decade in the making, The Office – a Facility Based on Change was the result. The goal – to investigate how the world of work operated – concluded, sadly, that ‘today’s office is a wasteland. It saps vitality, blocks talent, frustrates accomplishment. It is the daily scene of unfulfilled intentions and failed effort.’ It identified how the office had evolved – that this was no straight line evolution – and how new professions, new management styles, and the war of communications devices were influencing the office, and how all of this impacted the performance of people at work. It required a change, and Propst had the inordinate self-confidence to act. He understood that office users wanted answers, that the answers lay in the concept of an overall system, essentially one that could be perceived as the user’s own, responsive to individual needs, allowing employers to format their offices the way they wanted.

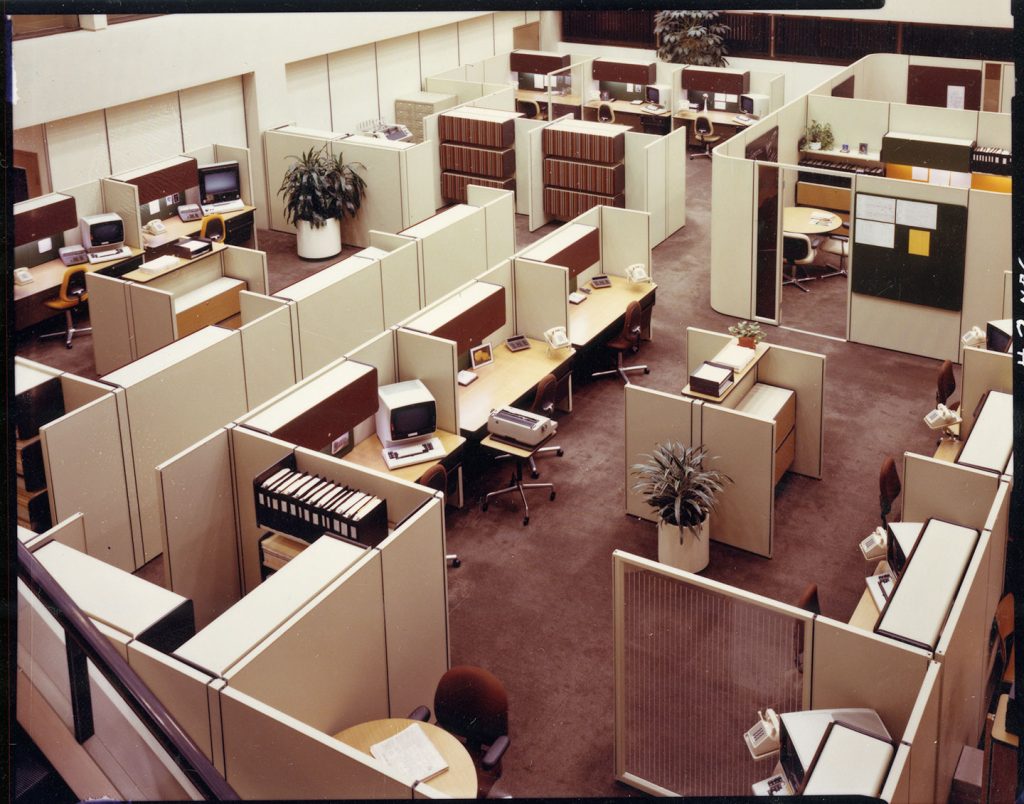

That was the start of Action Office, in 1964, with George Nelson working on the design. It was the world’s first open-plan office system, ‘a bold departure from the fixed assumptions of what office furniture should be’. It won an award but was not a success – in fact, it was a commercial failure. Nelson moved on but the product was developed further by Propst and Jack Kelley, and the revised kit of parts introduced in 1967, capable of modification to suit the changing needs of employees, became an unprecedented success, reaching sales of $5bn by the turn of the century. Today, Action Office is available from Herman Miller in the Americas, Middle East and Africa, though it is currently unavailable in Europe or Asia-Pacific.

Action Office took managers out of corner offices, and it took over the world of the office. Propst always saw the overall impact of creating an arena with people having access to, for example, more than one workstation and some storage, as well as ease of conversation. Its success was underpinned by understanding and responding to: the purpose of the organisation, support of individual performance and self-expression, the role of facility planning, and the art of ‘what if’ speculation – what Propst called ‘pre-gaming’. And he appreciated the potential and recurring conflicts: geometry versus humanism; the need to make changes with as much ease and grace as possible; the right to be different within an organisation.

Nevertheless, questions of privacy and security, enclosure and access were never far away from the discussion. But this was an infinitely flexible sub-architectural system that would provide a sense of place and purpose for the individual without sacrificing executive and staff privacy. Its success was in its simplicity. The partly enclosed offices that could be configured, became known as cubicles.

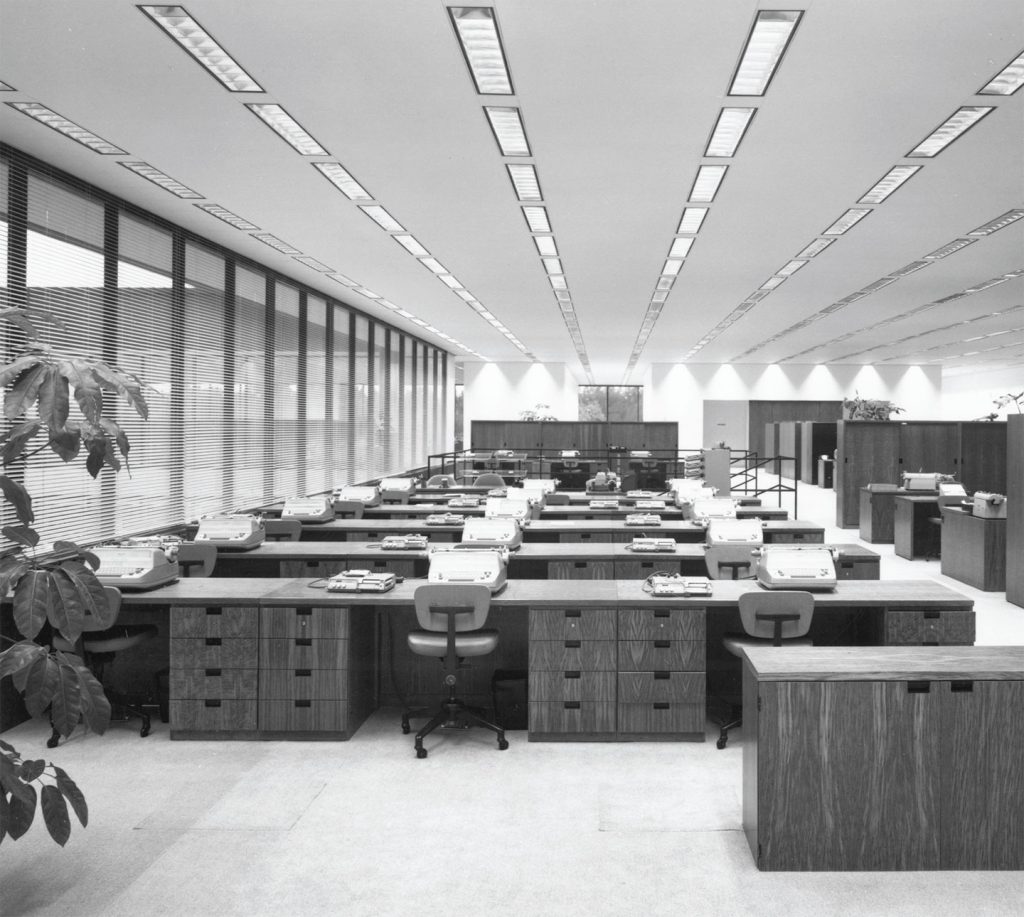

At the same time, in 1967-8, Roland Gibbard at Yorke Rosenberg Mardall (YRM) devised interior partitioning and furnishing systems for Boots’ head office at Beeston, UK – a low-rise two-storey building designed by Skidmore Owings & Merrill (SOM).

Surrounding the inner courtyard on the upper level was a continuous open-plan office area planned by SOM. The brief was detailed and specific as Boots emphasised the scheme had to allow for individual departments to contract, expand or be replaced with a minimum of disturbance.

This resulted in a bespoke system of 1,300 workstations and desks made up from purpose-designed kits of interchangeable components, giving great flexibility within the discipline of a module of 1.8m. Privacy for managers was achieved by the use of carrels of two sizes to the same height of freestanding filing and storage systems – a ‘carrel’ being a medieval monastic term for reading areas in a library and Gibbard’s name for cubicles. Everything was oak. Closed offices were glass-fronted, with internal screens of bronze glass. It was the most sophisticated, elegantly detailed, and successful demonstration of burolandschaft in the UK for the next two decades. It was also almost certainly the most expensive.

In 1969-70, Bruce Graham at SOM designed the largest cigarette factory in Europe at Hartcliffe, Bristol, together with a five-storey head office building, for tobacco manufacturing company WD&HO Wills. Like Boots, it featured similar high-quality interiors by Gibbard and Terry Addison’s team at YRM – but at a significantly lower cost per head.

Move on two decades and we arrive at multinational ad agency WPP, where it had became evident that the management and utilisation of office space was critical to the success of the overall business, and had a fundamental impact on the effectiveness of people at work and thus profitability. At the time, its 40 companies, including fellow ad agency J Walter Thompson (JWT), which it had acquired in 1987, occupied the equivalent of two and a half times the Empire State Building – 558,000m2.

The company needed to make the best use of that space, a fact accentuated with the purchase of the likes of Ogilvy Group in 1989, which only made matters more acute. There was just too much space.

Shortly after the JWT acquisition, Martin Sorrell, the group chief executive at the time, instituted the WPP Space Program that drew together real estate managers and advisors, and a team at WPP subsidiary Business Design Group (BDG) led by Alex Redgrave.

Its brief: to devise a workplace strategy and guidelines to deliver cost-effective real estate solutions that met individual business needs, manage and reduced total real estate costs, mitigate real estate liabilities, assist in overall planning, achieve best practice and, lastly, enhance the working environment for staff.

And to do that at a time when the workplace itself was rapidly changing to reflect advances in technology and working practices. For over a decade BDG had said it was ‘putting design to work’ for its clients ‘to improve efficiency in the workplace’. It was its raison d’être – to accelerate and sustain the performance, productivity and satisfaction of people at work. Now it had to do it for every part of its parent company. There was to be a great deal of rationalisation: flexibility became paramount.

We all need a place to work, are often aware of shortcomings in our working environment, but do not always have the vocabulary to articulate exactly what it is we want. The Space Program gave people the opportunity to be involved before the defining and setting of the strategic and operational objectives, the critical success factors that WPP demanded.

As key performance indicators for buildings became integrated into company business plans, its ideas were implemented almost immediately by BDG with the relocation of JWT in Milan and Ogilvy in Brussels, both designed by Lydia Randall.

With a global footprint spanning more than 100 countries, the idea of developing state-of-the-art campuses in the world’s top cities became essential for the overall success of WPP, to enable flexible working and seamless collaboration across marketing disciplines and agencies. With over 100,000 employees, 68,000 are today based in 47 campuses, most of which have been designed by Randall, and by 2020, work on WPP’s campuses accounted for 60% of BDG’s turnover. Capital expenditure on campus projects and real estate has now dropped, yet the process of restructuring and consolidation will always continue, as it always does with large, sprawling multinationals. As WPP faces what has been dubbed ‘its Kodak moment’ – the disruption to business caused by AI – the need to make the best use of its various properties around the world will always be essential.

The commercial property market has revived since the pandemic. Rising office rents in the UK have been attributed, in part, to a half million square metre shortfall in the supply of new or substantially refurbished office space in London. Some employers are doubling down on big offices while others move to smaller but better serviced properties. Property bosses are betting on workers returning to their offices. Some are demanding their presence.

From January, Amazon staff were expected in five days a week. JPMorgan Chase, which has just opened its newly built $3bn steel and glass, 1,388ft-high, 60-storey, 2.5 million square-feet global headquarters at 270 Park Avenue in New York, called for a full-time office return from March. The new building, designed by Foster, will eventually be home to 10,000 of the bank’s global staff of 317,000. WPP asked workers to return four days a week. British Land’s staff are also expected to spend four days a week at their desks. Citigroup is spending £1bn-plus upgrading its Canary Wharf tower, whereas HSBC is reducing global office space for 40%. Overall, though, offices are still in demand.

Management hates seeing empty seats knowing full well how much this real estate is costing them. A priority is providing flexible and adaptable spaces that are not just a place to work but a way to engage staff, build a better culture and deploy technology to improve employee interactions. Once again the talk is of collaboration zones, tech-enabled meeting rooms and quiet spaces – flexible layouts. As work patterns are always evolving, what is the future for the corporate headquarters? It’s time for creative designers to craft the space in new ways once more.