Edgar Martins’ photography takes us to strange locations and makes them stranger still. His latest project, The Time Machine, is the result of a ‘topographical survey’ of 20 hydro-electric power stations in Portugal. They penetrate a deserted industrial world, as if frozen in time and chanced upon by a future explorer.

In Martins’ photographs, the built environment takes on an uncanny quality. For example, in his A Metaphysical Survey of British Dwellings and Dwarf Exoplanets (Blueprint 296), a Potemkin village complete with British high street signs and built as a police training facility, becomes a dark dreamscape under a black sky. His 2009 series, This Is Not A House (at the New Art Gallery, Walsall, until 24 December) catalogues abandonment after the American property crash. In The Time Machine, as in previous projects, there is a sort of super-reality derived from Martins’ long exposure and lighting techniques, and the inference of an unseen human presence.

The Time Machine could refer to the absence of clues such as humans to date the pictures, or the periods when the facilities were built and their own futuristic aspirations. Under dictator António de Oliveira Salazar’s Estado Novo (New State) regime, hydro-electric was to power a vast industrialisation of Portugal, but even after his successor, Marcelo Caetano, was swept from power in the 1974 Carnation Revolution, the newly democratic country continued to invest in the renewable resource. Nowadays, local environmental grounds prevent plans for new

dams. Martins says: ‘The reason I photographed newer dams and power stations was to experience the difference between different projects,’ as well as ‘referring… to the failure of [Portugal’s] modernist project as a whole’.

The New State’s project may have failed, but the power stations still operate, upgraded examples of functional efficiency. Its obscure architects’ and engineers’ forms followed function, but were not immune to illusion or allusion. Take the Miranda do Douro power station, built 1957-61. Martins’s shot of the machine hall shows walls of brick, actually a purely superficial surface covering the whole plant, and delicate curving supports reaching to a blue-painted barrel ceiling evoking sky or water. The equivalent but vaster space at Fratel (built 1973) cuts curves in graceful brutalist structural concrete. Unlike Salazar’s strange heroic Lisbon monuments, Martins sees the hydro-electric architecture as ‘more European and progressive’. Elsewhere, designers like Pier Luigi Nervi in Milan were happy to engineer aesthetics into concrete. Martins feels the New State designs show ‘a willingness to mark and celebrate’ the ‘heroic political will’ of the era, bewitched with technology.

Control rooms date these places. At Lindoso, designed in the Sixties, a great grey bank of manual controls sits heavily before a yellow wall of gauges, as if in a sci-fi B-movie. Travel forward in time to when the biggest Portuguese dam at Alto Lindoso was completed in 1993, and big boxy computer monitors and chunky keyboards seem to reflect the retro-futurist early digital period. What’s missing, of course, is the boffins to man this kit. Some facilities were designed for hundreds of staff, but are now run by half a dozen. ‘What can now be considered false expectations,’ says Martins, ‘stem from projects conceived when man and machine formed part of the same future’, but then machine control was automated, and the images are ‘a testimony of the link that has been broken’.

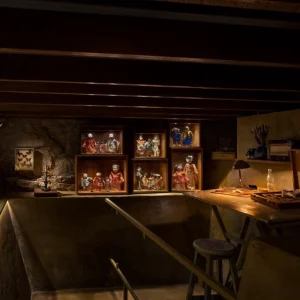

Despite Martins’ trademark lack of humans, he is fascinated by traces of the human touch: a pot plant at Miranda, a rumpled carpet at Alto Rabagão that seems to be lapping like the sea at an empty chair. Look closely into Fratel’s machine room and you’ll find a suspended nativity scene in neon, almost lost in the vast cavern.

The Time Machine is more than industrial photography that scrupulously documents structures, like the Bernd and Hilla Becher pictures of water towers. It is also an exercise in what Martins calls ‘suspended time’, and it explores ambiguities about built space. His straight-down view of the Pocinho unloading dock, for example, abstracts it into a flat, oblong motif.

There are many things in these images: a nostagia for retro-future, a reverence for technology, a play with scale, and not least a disquieting, mysterious emptiness. The only exterior shot is of a water intake tower at Caldeirão, shot on a foggy morning. A natural optical illusion suggests its shaft contains a field of rocks: another mystery in a mesmerising collection that warrants tranquil contemplation.

Simultaneous exhibitions of The Time Machine run at the Wapping Project, London SE1 and the Museu da Electricidade, Lisbon, until 5 November.