THE TRIBUTES to Sir Nicholas Grimshaw following his death in September at the age of 85 were, as obituaries necessarily are, broad-brushstroke summaries and assessments of his achievements: the key projects (the Eden Project, the International Terminal at Waterloo), the milestones (the partnership with Terry Farrell, the foundation of Grimshaw Architects in 1980) and the medals (RIBA Gold Medal in 2019).

So not surprisingly, no one touched on his particular contribution to lighting: his understanding of its fundamental importance in architecture and the recognition of, and respect for, lighting design that his practice demonstrated from its early days.

There has always been a group of architects who grasped that light and shadow were as intrinsic a part of a building as bricks and mortar or concrete and steel. As Louis Kahn, famously a member of the architectural illuminati, once put it in a lecture: ‘Light, the giver of all presences, is the maker of a material, and the material was made to cast a shadow, and the shadow belongs to the light.’

In the 1980s and early 1990s, when the lighting design profession was establishing itself in the UK, its practioners spent a deal of time and energy explaining to architects and designers what they did and why it was an essential component of the design process.

The Grimshaw practice needed no such convincing, engaging Jonathan Speirs of Lighting Design Partnership – before he went on to form what is now Speirs Major Lighting Architecture with Mark Major – to undertake the lighting scheme for the Waterloo International Terminal, which opened in 1994. Waterloo won the RIBA Building of the Year and the Mies van der Rohe Prize.

Andrew Whalley, who succeeded Sir Nicholas as chairman of the practice in 2019, acknowledged in an interview with Arc magazine, that attitudes then were very different: ‘I think it has changed a lot… because when we did Waterloo, bringing in a lighting designer was fairly exotic – lighting designers were for theatre, and seldom used on public buildings, and the array of lighting fixtures available was much more limited.’

In the same way that the practice approaches each project as a unique proposition, with sustainability at the core and ‘driven predominantly by function and performance’, it has always collaborated with different companies, including lighting designers, according to the needs of the project. Speirs Major, WSP, Cundall Light4 and GIA Equation are among the consultancies that have worked with Grimshaw.

‘We work with a whole range of firms, in the same way that we work with different engineers, different structural engineers, different mechanical engineers,’ Whalley told Arc. ‘And the nice thing about working with different consultants is it’s the same as when you work with a different client on a different project, you come up with a concept that’s appropriate to that, with a team that’s appropriate to the demands of the project, that’s tailor-made to that project’s particular needs.

‘So we’ve always worked very closely with lighting designers in our projects, and recognise their importance. It’s not something we do, it’s something that we collaborate on.’

Crucially, because Grimshaw believed that lighting designers were integral to the design and build process, he also understood the importance of their early involvement. ‘It’s important that you have an empathy with them and you work in partnership with them,’ he told Amanda Birch in an interview for Lighting (Illumination in Architecture). ‘Rather than design a building and ask them to light it, you have to work with them from the beginning of the concept, especially if lighting is a key issue.’

He also believed that architects should have a better grasp of lighting. ‘There should be courses in light incorporated into architecture degrees,’ he told Birch.

‘Young architects may then have a keener interest in lighting if they were taught it well and given lectures by good lighting designers. The theory of lighting should also be covered as it’s very technical.’

While embracing the need for artificial lighting, in the same interview he expressed his dismay at its overuse in contemporary buildings. ‘Lighting levels could easily come down by 50%,’ he said. ‘We’re still not designing for the computer age. Nearly every office building that comes up for let is fitted out to Category A, with suspended ceilings and banks of unnecessary lights – nobody wants this anymore.

‘Computer-based tasks simply don’t need such high levels of artificial lighting,’ he continued. ‘There is huge scope for designing buildings with filtered daylight and very low, background light. Buildings could have pools of daylight, and a lot of the artificial lighting in between could be completely done away with.’

His projects featured creative ways of exploiting natural light and bringing daylight deep into buildings, not only for sustainability reasons but also for the well-being of occupants.

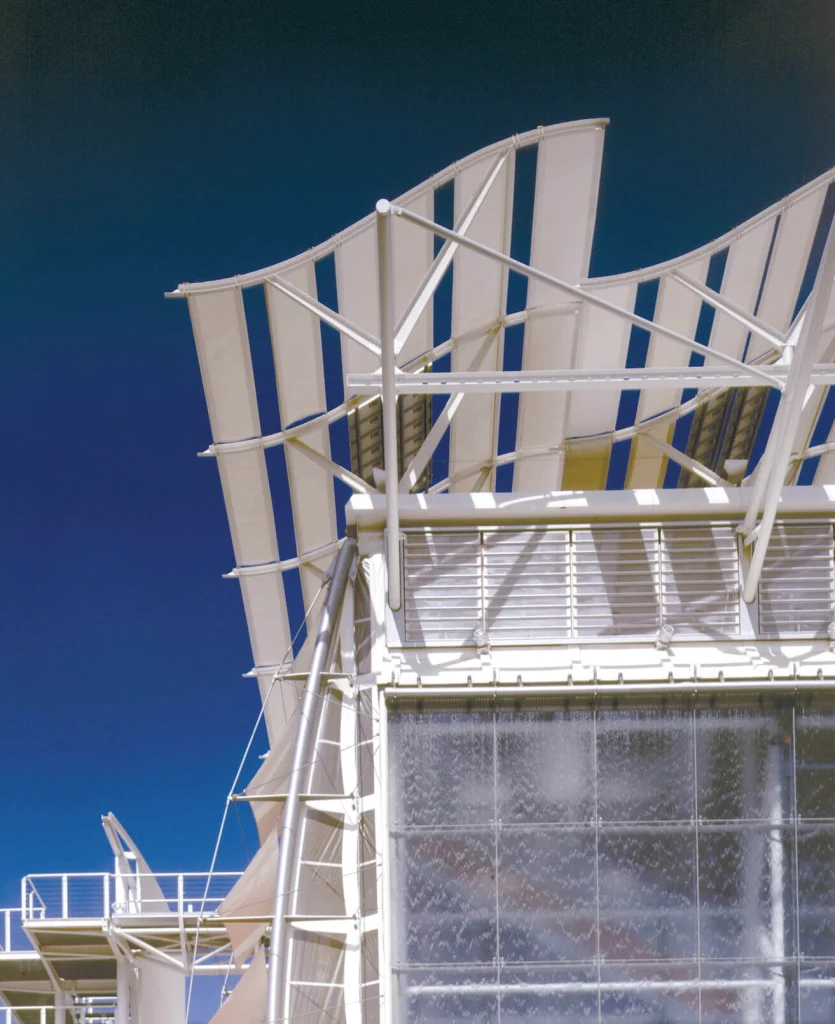

The 1993 Cologne headquarters and factory for Igus, maker of high-performance polymers, featured roof domes to draw in north light down to workbench level and included four landscaped courtyards, planted to represent each season, which acted as rest centres for workers.

More recently, and spectacularly, his Fulton Center, the transit hub in Lower Manhattan, New York, featured a canted 16.15m-diameter circular skylight known as the ‘Oculus’, which brings sunlight and daylight through the building to the subterranean levels beneath.

The effect of the natural light is magnified by an integrated artwork, the Sky Reflector-Net, a steel cable-net structure that forms an independent reflective lining, offset from the dome’s interior, and which directs sunlight downwards. The two elements together provide sufficient illumination to the building interior to allow electric lighting to be turned off during the daytime.

The concept was created by James Carpenter Design Associates (JCDA), and its design and development was down to an engineer/architect/artist collaboration between Arup, Grimshaw and JCDA. ‘The raison d’etre of the whole scheme was to bring daylight through the Oculus at the top, right down to the two levels below ground,’ explained Grimshaw.

From its first project, the Grimshaw practice has viewed architecture and industrial design as inseparable disciplines, an approach that has occasionally meant venturing into the design of lighting systems. Together with what was then Speirs and Major, lighting consultant for the project, Grimshaw created a bespoke lighting solution for the St Botolph Building in the City of London in 2010. This involved a simple lighting boom designed to integrate within a central glass and steel atrium lift lobby and bridges.

More recently, as part of the consortium with Atkins, GIA Equation (lighting consultant) and Maynard, Grimshaw collaborated on the lighting systems as part of the line-wide identity for London’s Elizabeth Line. The key fittings were the cross passage booms by Designed Architectural Lighting (DAL) and the Totem uplights and escalator deck uplights by Future Designs.

Grimshaw also memorably designed the classic Tecton continuous-row lighting system with Zumtobel, released in 2001. The new Tecton II, revisited by Pininfarina, is the latest of several iterations, including an LED version in 2010.

‘For us, Tecton was the first product that followed a “design-led” approach – without us even realising it at the time,’ says Mario Wintschnig, product manager of Zumtobel at the time.

While its founder has gone, it’s clear that the understanding and appreciation of lighting is deep in the practice DNA.

‘When you’re coming up with the bare bones and skeleton of the project, it’s just about form creating, but within that, quite soon afterwards you have to think about the whole experience,’ said Whalley in the Arc interview. ‘Not all of our projects benefit from the availability of natural light, so the integration of lighting is absolutely the experience of the space – it’s got to be thought of from the beginning.

‘So I think how you integrate lighting into the architecture, so that it’s seamless, and just becomes a natural part of the architectural experience, is absolutely critical.’