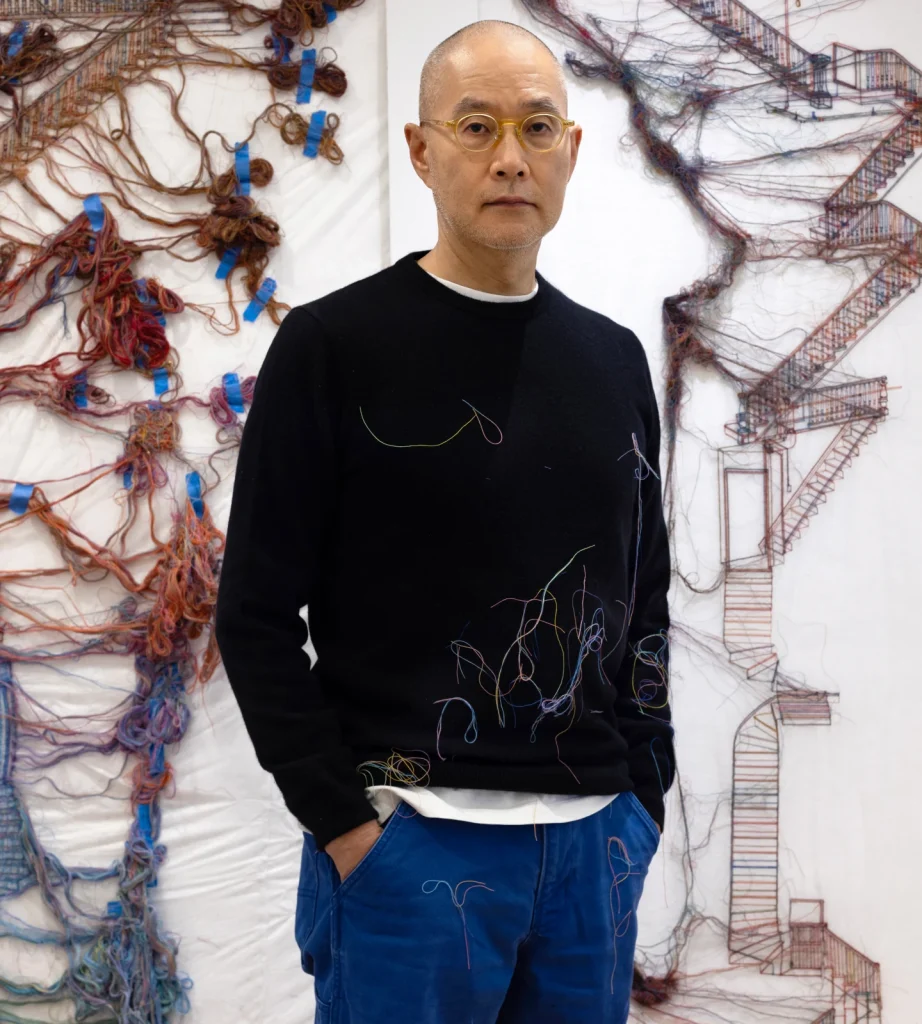

FEW ARTISTS navigate the intersection of personal history, architecture and memory as evocatively as Do Ho Suh. Best known for his ethereal fabric sculptures of domestic spaces, the South Korean artist has spent decades constructing intricate homages to the buildings in which he has lived, all the while ruminating on the notion of home as both a physical structure and a deeply emotional experience. This spring, Suh’s large-scale installations, sculptures, videos and drawings are the subject of a major survey at Tate Modern, the artist’s largest in London since 2002. Bringing together works from the past three decades, Walk the House (1 May – 19 October) examines the complex relationship between architecture, the body and the memories that shape our lives, inviting visitors to join the artist in pondering the enigma of home: is it a place, a feeling or a construction of the mind?

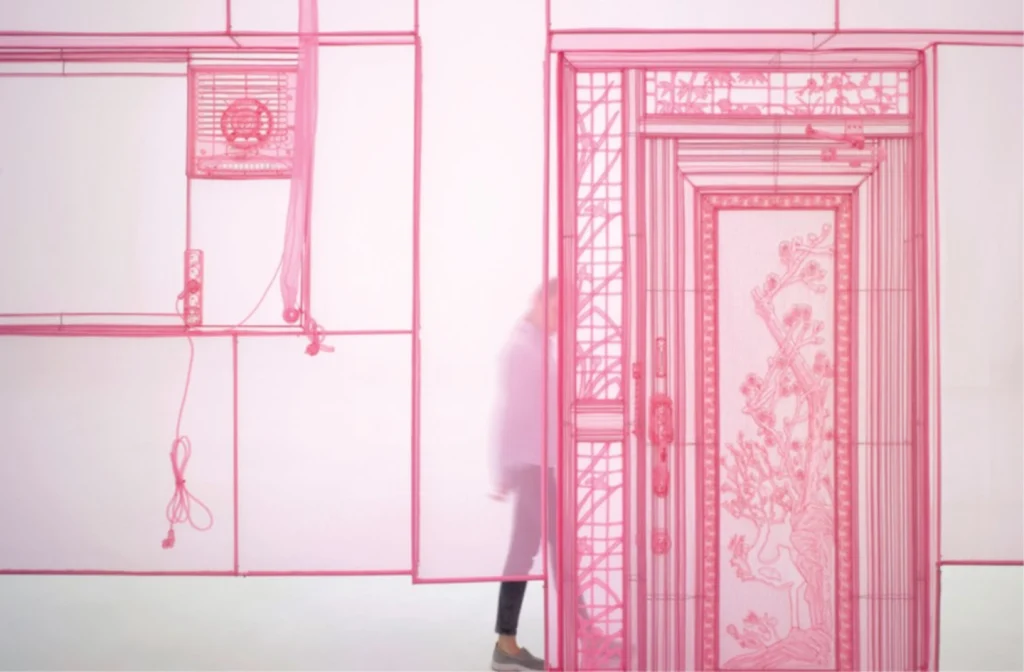

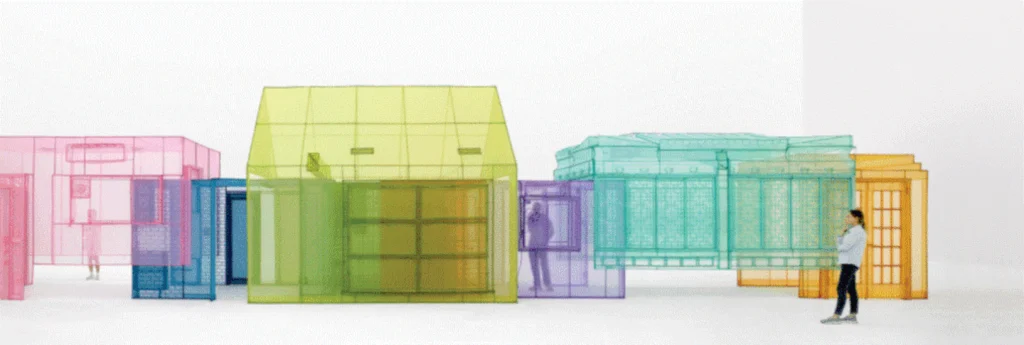

Born in Seoul in 1962, Suh has led a relatively itinerant life, moving between cultures, languages and architectural surroundings. He initially studied traditional Korean art in his home country before migrating to the US in 1991, where he received a BFA in painting from Rhode Island School of Design in 1994 and an MFA in sculpture from Yale University in 1997. Since then he has based himself in New York, Berlin and London, frequently hopping back and forth between these locations. In the late 1990s he began exploring themes of place and identity by making brightly coloured one-to-one scale fabric sculptures of architectural interiors. Using diaphanous sheets of polyester, he has obsessively recreated his childhood home in South Korea and apartments and studios in Berlin, New York and London. ‘My architecture pieces are all basically outlines,’ Suh has said of these walk-through sculptures that, supported by simple steel frames, give form to ideas about ideas about migration, displacement and transience. Several are on show at Tate Modern and, though they appear as precise as blueprints, Suh concedes that these ghostly structures are not 100% accurate. ‘People think they are really precise,’ he has said. ‘But, of course, I’m not actually trying to exactly replicate a physical structure in fabric. It’s more about capturing enough visual and physical information to evoke a sense of the space as I experienced it.

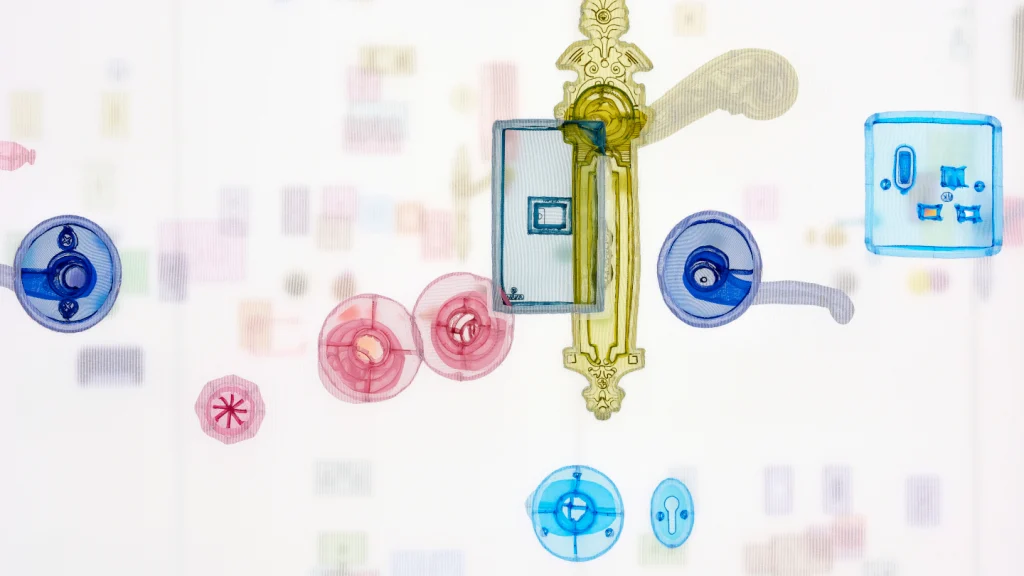

‘Home started to exist for me when I no longer had it,’ said Suh, who regularly brings together multiple interior spaces in single installations. Referred to as ‘Hubs’, these composite works invite visitors to explore interconnected rooms, corridors and entranceways that replicate domestic spaces from the cities in which the artist has resided. They are crafted using a combination of traditional Korean sewing techniques and cutting-edge 3D modelling and mapping technologies. Each one is filled with carefully embroidered architectural features, including door handles, electrical sockets and light switches. As you walk through these fragile structures it feels as though you are travelling back through time, moving between cultures, countries and even psychological states. ‘Practically it’s impossible to have all these spaces in one place,’ Suh has explained. ‘So the work is related to my long-held desire to blur the boundaries of geographical distance.’ Indeed, the notion of collapsing space is central to these works, which the artist describes as ‘suitcase homes’, a term that relates to a Korean expression referring to the hanok – a house that could theoretically be disassembled, transported and reassembled at a new site. As Suh has said, his desire is to ‘carry my home with me all the time, like a snail’.

Besides his fabric works, Suh is known for his labour-intensive Rubbing/Loving projects, in which the contours of architectural surfaces are recorded through rubbing with graphite or coloured pencil on paper. One of the most ambitious of these, and on show at Tate Modern, is Rubbing/Loving Project: Seoul Home, 2013-22. The decade-long endeavour began with the artist completely covering his childhood home in Seoul with hundreds of small sheets of Mulberry paper. Suh then painstakingly traced each contour and texture of the building, rubbing every surface with graphite, from its terracotta tiles to its wooden beams. ‘It’s like caressing a surface, like you caress your lover,’ Suh has said of the process. ‘There is also a level of intensity because you can’t slacken, you cannot miss an area. You have to cover every surface. So there is a lot of devotion and caring through the process.’

Suh’s house, which was designed by his father (a respected Korean philosopher and ink painter) in the 1970s, is a traditional Korean home based on a building in Gyeongbokgung Palace, the main palace of the Yi dynasty in Seoul. Built out of concern for the loss of Korean tradition as vernacular residences were being torn down and replaced by modern housing blocks, the home symbolises the father’s desire to preserve Korean tradition. Suh’s paper stayed fixed to the building’s exterior for months, becoming weathered and worn before being cut away and painstakingly reassembled onto a wire frame to form a ghostly replica of the house. For Suh, his childhood home is a very special place, filled with memories of his upbringing and the special relationship he had with his father. This is why he has revisited the building time and time again, creating numerous pieces based on its interior and exterior spaces. ‘This is where my father spent most of his time’, Suh has explained. ‘All my upbringing was located there. The house is like a self-portrait, but it’s a portrait of my father as well.’

The title Rubbing/Loving plays on the difficulties that native Korean speakers encounter when pronouncing English words beginning with the letters ‘R’ and ‘L’, which results in them sounding almost identical. But for Suh, the action of rubbing is also associated with love. ‘The gesture of rubbing is basically very caring,’ he has explained. ‘There were multiple levels of emotion I went through during the process. A lot of memories had been accumulated within the space, and a lot of marks had been made there. Some I remembered before I started to do the rubbing, but some I completely forgot and I rediscovered them as I rubbed.’

For the large-scale installation Rubbing/ Loving, 2016, Suh memorialised the interior of the New York apartment on West 22nd Street where he had resided for 18 years. As before, the process began with covering every surface with paper, including the cabinets, light switches and doorknobs but this time he used coloured pencil and pastel to create his rubbings. ‘This project didn’t become possible until I had to vacate the space,’ Suh recalled. ‘When my landlord passed away, the building was sold and I had to move out. I decided that the last piece I would make in the space would be a rubbing of all the interiors in the entire building.’ Suh spent two years on the project, meticulously rubbing and caressing every surface with his fingertips. In doing so, he indexed every scratch, dent and imperfection – the accumulated vestiges of a human presence. Just as Seoul Home became a poignant memorial to the artist’s father, the process of making this work became ‘an extended ritual’ to commemorate his time in the house and his warm friendship with his former landlord, Arthur. At their core, these Rubbing/Loving projects speak to the transient nature of home, memory and the emotional imprints we leave behind in the spaces we inhabit.

Among Suh’s smaller pieces on display at Tate Modern are his Thread Drawings, works on paper made using threads stitched into soluble gelatin tissue. These are sewn in the same way as his architectural fabric sculptures and feature a similarly vibrant colour palette. But once immersed in water, the gelatin dissolves and the threads fuse with the handmade paper, leaving skeletal images of architectural facades, staircases light switches, fire extinguishers and other motifs familiar from the artist’s large-scale works. Suh developed the process during a residency at Singapore Tyler Print Institute in 2010, creating pictures that lie somewhere between two and three dimensions. Staircase, Ground Floor, 348 West 22nd Street, New York, NY 10011, USA, 2016, takes the form of a red staircase yet at the same time appears like a discarded negligee. Drawing out connections between architectural space, clothing and the body, such works underscore Suh’s fascination with the interconnected spaces we inhabit and their relationship to identity formation. In contrast, other, cartoon-like drawings, such as My Homes, 2010, anthologises an array of zany and humorous concepts: a house that runs on legs or that radiates out of the artist’s head, or lies balanced on his shoulders.

More recently, Suh has begun using video to explore his themes, most notably in the 2018 installation Robin Hood Gardens, which documents the interiors and exteriors of the condemned Robin Hood Gardens housing estate in Poplar, east London. Suh’s panoramic film, which was commissioned by the V&A for the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale, employs 3D scanning, photogrammetry, time-lapse photography and drone footage to create an intriguing portrait of the iconic 1972 brutalist housing estate designed by Alison and Peter Smithson. The camera pans vertically and horizontally along walkways and through the building, moving from one domestic interior to another to create a visual journey that addresses notions of home, memory and displacement within a physical structure on the verge of demolition. Suh was particularly drawn to the site’s ‘intangible quality’ as much as its architectural structure: the ‘energy, history, life and memory that has accumulated there’.

The exhibition culminates in a space dedicated to Suh’s ongoing Perfect Home: The Bridge Project, for which the artist, working with a team of architects, engineers, programmers and animators, has developed a series of speculative prototypes for bridges that propose ways to connect his home in Seoul with his home in New York. Each bridge uses different technologies and structures to contend with issues of climate, geology, biodiversity and human activity. One runs over the Arctic, cutting a path through buildings and mountains, while another follows a straight path between the two cities. The latter crosses the Pacific on a series of floating pods with special mechanisms designed to keep them stationary despite the ocean’s restless currents. Presented as an experimental lab within the gallery space, the project features drawings, animations, videos and specific environmental datasets covering ocean currents, tides, wind, temperature, precipitation, natural disasters, the migratory routes of aviary and marine life, and so on. The plans also take into account geopolitical factors such as missile testing, as well as the migratory patterns of humans via air, land and ocean. It’s a fantastical project, whose imaginary links between disparate places and cultures reflect Suh’s enduring interest in the relationship between identity and globalisation.

With issues of migration and displacement increasingly at the forefront of current affairs, Suh’s sculptures, drawings and videos seem more relevant than ever. The pieces on show at Tate Modern ask profound questions about the nature of home and what it means to belong. Home, they suggest, is not a fixed place but a shifting, spectral presence – something that exists as much in memory as it does in reality. The built environment is revealed as a witness to the traces left by those who inhabit it and, in Suh’s attempts to recreate and remember aspects of former and current homes, he demonstrates the impossibility of truly preserving something, whether a place, a moment in time or a memory. For anyone who has felt the pull of nostalgia or the upheaval of displacement, the artist’s works serve as a reminder that home is not just where we have come from, but something we carry within us.

Frequently asked questions

-

Who is Do Ho Suh and what is he known for?

Do Ho Suh is a South Korean artist renowned for his ethereal fabric sculptures that explore themes of home, memory, and identity. His works often recreate the architectural spaces he has inhabited, inviting viewers to reflect on the emotional significance of these environments.

-

What themes does Do Ho Suh explore in his work?

Suh's work delves into themes of migration, displacement, and the transient nature of home. His installations and sculptures reflect on how identity is shaped by the spaces we inhabit and the emotional imprints we leave behind, making his art particularly relevant in today's context of global movement and change.

-

What is the focus of Do Ho Suh's exhibition at Tate Modern?

The exhibition, titled "Walk the House," runs from May 1 to October 19, 2025, and showcases a comprehensive survey of Suh's work over the past three decades. It examines the intricate relationship between architecture, the body, and memory, encouraging visitors to contemplate the concept of home as both a physical space and an emotional experience.

-

How does Do Ho Suh create his fabric sculptures?

Suh constructs his fabric sculptures using diaphanous sheets of polyester, meticulously recreating interiors from his past homes. These sculptures are supported by simple steel frames and are designed to evoke the essence of the spaces rather than serve as precise replicas.

-

What are the Rubbing/Loving projects by Do Ho Suh?

The Rubbing/Loving projects involve the artist creating detailed rubbings of architectural surfaces using graphite or coloured pencil on paper. This labor-intensive process captures the textures and contours of the buildings he has lived in, serving as a poignant memorial to his experiences and the memories associated with those spaces.