In a wide-ranging and often raucous debate, lighting design came under the spotlight – if you’ll excuse the pun – in the latest FX Design Seminar.

Lighting designers came in for some flack for not being there at the sharp end of project pitching with designers and architects, while receiving sympathy for not being fully understood by neither clients nor quantity surveyors, especially when it comes to the bottom line.Most of the gathered group of suppliers, specifiers and designers felt lighting designers should be onboard from the start of a project to fully realise a vision, and agreed that the development of new lighting technology has both pros and cons. They felt that the plus side of enhanced performance, new lighting effects and better sustainability credentials is tempered by new technologies coming to market perhaps too quickly – particularly LED – and using live projects as test beds, along with the designer’s tendency to go overboard with anything new rather than just adding it to the lighting tool arsenal.

The debate kicked off by looking at the lighting design profession itself: where it has come from and whether there’s a clear training path for budding designers. Lighting designer and director of Light and Design, Lee Prince, pointed to the origins of the business in New York in the late Sixties and from the Seventies in the UK, adding that he’d seen a lot more people coming into the industry in the past seven to 10 years.

That said, there’s still no clear path to becoming a lighting designer. Lee’s found, while putting together lighting-design teams, that those who have come up via theatre lighting tend to be less technical, while those that have come from a manufacturing background don’t necessarily understand ‘how to work creatively with light’.

Max Eaglen, managing director of design consultancy Platform, took that one step further, adding that in his experience, ‘I see a noticeable difference between theatrical and architectural lighting designers.When you use a theatrically based designer they light the event or the interior really well, but often the lighting is bulky and not discreet and the heat can be just amazing. On the flip-side, architecturally based designers often choose quite discreet lighting, but they are a little bit dull. Finding the balance can be quite tricky.’

Martin Preston of lighting manufacturer Lutron agreed, and added that for an architect or designer to truly realise their design vision they need to be thinking of lighting right from the beginning: ‘I always say, if you are sitting down with pen and paper to do a design, be it a building, hotel, retail or office, and you are choosing a particular type of finish, surely you must think about how the lighting is going to affect that material. Unless you work with a lighting designer how are you going to achieve what you want?’

He added that environmental issues that have come to the fore are helping to bring lighting and designers and architects together earlier now. MET Studio CEO lexMcCuaig also feels it is important to work closely with lighting designers at an early stage, but brought up the thorny issue of cost.

‘I always think it’s about money,’ he said. ‘We call the lighting designer if we have a big project; if it’s small; we say “Let’s not call the lighting designer.” You’re torn – but that’s the truth.’ And McCuaig went on to castigate lighting designers for not getting in early enough on projects – at the pitch stage – and being prepared to share some of the risk and cost involved in that, adding that this would earn them more ‘respect’ from interior designers and architects.

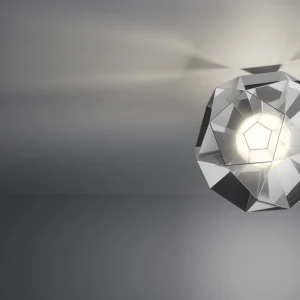

Ken Giannini, interiors director at Scott Brownrigg, said he believed there was generally more focus on lighting now because the products were so much better both in terms of performance and product design, opining that some lights are ‘so beautiful they make you want to use them’.

He then brought the conversation around to whether we should use lighting as decoration, while admitting ‘I do really enjoy external lighting on buildings. I personally struggle because I know it’s completely wasteful and decorative, but it can be really special and spectacular.’ However, Lutron’s Anoushka Sulley pointed out that it did have a function. ‘It draws people in – so it’s necessary in that sense,’ she said.

Taking the Thameside as an example McCuaig responded that if every single building was lit we’d be less impressed, or to use his exact words ‘it would look crap!’ – likening it to Moscow. Ken Giannini agreed: ‘Moscow is like that – it’s like Piccadilly Circus everywhere – it’s really disgusting. It reminds me of what my architectural tutor said – “It’s like wearing a tuxedo every day of your life!”’

While a consensus formed that lighting actually did require some sort of overall state control, Lee Prince moved the discussion on, asking, ‘When does lighting exteriors change from lighting to branding, or from branding to advertising?’

He said the increased use of LED lighting systems that can show animated images were good for grabbing the attention initially, but their appeal begins to wane and they need to keep changing: ‘It’s becoming about content – that’s not lighting.’ Again he argued for more state control to avoid having ‘Vegas in every city’.

Max Eaglen chipped in with an example of a project Platform had proposed, which was interactive, whereby the public could touch screens that would make lights shoot up the building like fireworks. The client loved it – the planners threw it out. So there is an element of control at work. But he added that it was important to remember that done well, ‘there is a beauty in light that can captivate – you only have to look at the London Eye’.

Talking about LED introduced the subject of new technology in the lighting industry, which Lee Prince picked up, accusing the lighting manufacturers of using designers as guinea pigs. ‘Some manufacturers are addressing sustainability issues with decorative fixtures, but unfortunately the response to it has been LED lighting which we’ve all seen proliferating,’ he said. ‘In the rush to get these products to market and recoup their R&D costs, the full testing hasn’t been done and the LED manufacturers are using our projects as test beds to figure out if their lights work.’

Linked to sustainability and environmental impact is the question of control, and Damian Hodgson, creative director at 3D Reid Architects, said these factors are instrumental in bringing lighting design to the fore, along with things such as BREEAM legislation, which means the clients start to drive the issues. Continuing with an example of an office with a high level of individually controlled lighting for different spaces he added: ‘When you start getting zones that close down or dim when they are not in use and you get clients talking about BREEAM legislation, that’s when everybody starts to get interested – lighting gets on the agenda in a way it hasn’t been previously.’

Continuing the control theme, Paul Priestman, director of Priestmangoode, talked about his work on the new Airbus super jumbo and how the interiors are completely controlled by coloured light: ‘This was one of the driving forces from Airbus. It’s very expensive to change panels in an aircraft once it’s in flight. So by washing the panels we can give it a cool blue hue for, say, British Airways and when that aircraft is then sold on – because they are all owned by banks not airlines – you can then easily change the colour palette of the whole aircraft interior.

‘Lighting was absolutely key – the whole interior design is actually designed around the lighting effects. It’s all LED and fibre optics and it’s a very advanced system, computer-controlled and highly complex.’ Bringing the conversation back around to an earlier point, he added: ‘Interestingly, we worked on it with some lighting engineers from the theatre industry, from Germany.’

And while talking about state-of-the art developments in lighting design, SCIN director Annabelle Filer, brought up the issue of materials. She believes that whereas lighting often used to be about bringing out the best in the materials, the materials themselves are now becoming, in effect, part of the lighting solution – particularly with new surface-coating techniques and the ability to slice material incredibly thinly, making them more diaphanous.

‘There are some incredible things going on, particularly the use of reflection and looking at density of colour,’ said Filer. ‘There’s a coating called Super Nova that’s been developed for telescopes and it takes every single reflection out. On the other side is the development of “superwhites”, based on biometrics where they looked at beetle coatings and asked why are they so white.

‘The 0-size materials, as I call them, are also important. Technology is allowing us to slice stone ever more thinly – allowing you to move on in terms of the quality of the light.’

But Filer also pointed out that at her materials consultancy ‘in the four to five years we’ve been going, we’ve only had two enquiries related to light. Designers and architects are much more concerned with the tactile or functional nature of the material rather than, say, the theatrics.’

Conclusions? Well, the debate was too wide ranging to put the world to rights and what’s more, it carried on well after its allotted slot, until someone used the dimmer switch on that great big light in the sky (or is it computer controlled?)

This article was first published in FX Magazine.