IT SEEMS THAT wherever in the world you are, climate troubles are increasing. ‘A few years ago it was a future problem – now everyone can see that the issue is not just climate change but the weather events that are happening as a result,’ says Anica Landreneau, HOK’s global head of sustainability. ‘I’m based in Washington DC and we are seeing extreme temperatures including heatwaves that cause derecho storms with hurricane-strength wind and hundreds of lightning strikes an hour.’

For Dr Emna Bchir, architect and professor at the National School of Architecture & Urbanism in Tunis, it is extreme weather events, including prolonged droughts, heatwaves and erratic rainfall, leading to alternating episodes of flooding and drought, that are hitting her country the hardest. ‘The UN considers there is water stress when annual water supplies fall below 1,700m3 per person. In Tunisia, we used to have 500m3, but that has now dropped to just 350m3, which is defined as absolute water scarcity.’

The cost of not adequately preparing for extreme weather events is huge. The Association of British Insurers announced that 2023 brought record-breaking claims for weather damage, with the industry having to pay out £4.86bn, the equivalent of £13m every day, to cover business and homeowners’ claims for damage caused by high winds, flooding and freezing pipes. In other parts of the world it can be far, far worse – the severe storms in the US last year cost the country $182.7bn and nearly 600 lives, while the 2023 heatwave in France, one of the hottest summers on record, caused around 5,000 deaths.

With the stakes being so high, it’s not surprising that architects and engineers are working hard to mitigate the problems, and while some are turning to technology, others are finding inspiration in much older solutions.

Feeling the heat

Bchir recently addressed COP29 as part of her role as co-director of the Union Internationale des Architectes (UIA) Sustainability Commission, but is frustrated at the slow pace of international action and the lack of ambitious follow-through. At home, she is working with the UIA on a book called Wisdom of Tradition, which is advocating for the dynamic use of vernacular architecture to enhance traditional methods of climate adaptation, making them contemporary and more widely adopted by local populations.

‘I work a lot on vernacular architecture and we have a long built history of 3,000 years – we had bathrooms inside houses in 700BC, so there’s so much to learn and reuse. I don’t say “learn from the past”, because the word “past” has connotations that something is outdated, but this is the wisdom of thousands of years; adapting buildings to their surroundings, using local materials and building in the most economical way with no waste. Technology and science are very important, but it’s also important to reflect and rediscover these ancient solutions.’

Among these solutions, she counts mashrabiya screening, household water reservoirs, mud architecture, vaulted structures, naturally insulated terraced roofs and passive ventilation as tried-and-tested local methods that could have a wide role in the modern world – despite some issues with modern building codes. ‘All vernacular architecture has a low carbon footprint. Every country’s architecture has something that’s uniquely adapted to that environment; it’s part of our role as architects to analyse this wisdom and reuse these solutions, and the role of politicians to validate these solutions and make codes to support them.’

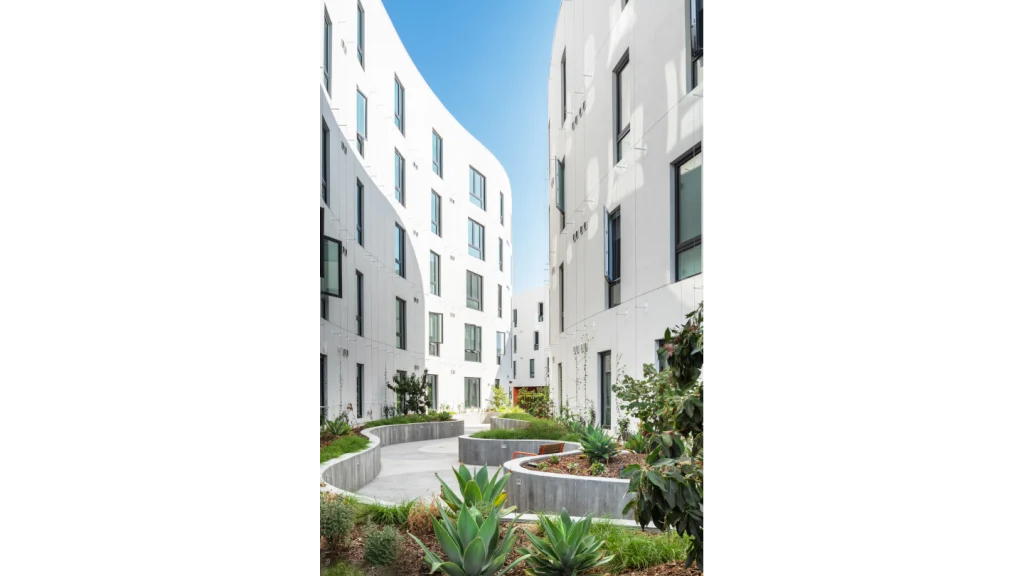

In Tunisia, the Hôtel Ksar Rouge in Tozeur, created by architects Tarak Ben Miled International, and the Ibrahim El Khalil Mosque in Tunis by Lotfi Rejeb, both stand out to Bchir as examples of this vernacular wisdom – but architects elsewhere are also picking up on many of the same ideas. A new housing complex in Los Angeles, Corazón del Valle, was designed by Perkins & Will in three curved masses, carefully designed to funnel the prevailing winds into the courtyard, gardens and homes. In a similar vein, the Ayla Golf Clubhouse in Aqaba, Jordan, was designed by Oppenheim Architecture with openings to capture coastal breezes, and mashrabiya-inspired perforated Corten steel screens, to keep the building cool.

Massachusetts-based CambridgeSeven drew from traditional Arabian architecture for its College of Life Sciences in Kuwait, where locals contend with 49°C temperatures, sandstorms and occasional flash floods. ‘As global temperatures rise, the Gulf region has become hotter than the traditional weather patterns would predict,’ explains principal Marc Rogers. The location’s extreme heat, dry air and the intense solar glare were managed through the use of mashrabiya and large atria that act like heat chimneys, passively drawing cool air up through the building. Similarly, in the KAPSARC centre in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, HOK channelled breezes through the centre of the site, provided screening and sunshades, and channelled storm water to provide a cooling garden, all helping to mitigate temperatures in a country where 1,300 pilgrims died last summer when temperatures in Mecca hit 50°C.

Turning the tide

For the more temperate parts of the world, excess water is probably the most pressing problem, whether from flash flooding or rising sea levels. ‘In New England, the advent in recent years of torrential rainstorms each summer and the subsequent flooding has made stormwater design a very high priority,’ says Adam Mitchell, principal at CambridgeSeven.

Meanwhile Dimitris Linardatos, partner at Price & Myers is concerned that water f lows in UK rivers are increasing so fast, that even buildings completed a decade ago may now be at risk. ‘Designing new buildings to be safe from flooding in the long term is the biggest challenge in the UK,’ he says, explaining that for pre-2016 developments, the guideline was that water flows in rivers would increase by 20% in 100 years due to climate change. In 2016, however, there was a reassessment, showing increases of up to 52% on the horizon in some areas, such as the Weaver Gowy management area in Cheshire.

‘These adjusted allowances for climate change show that the flood risk could have been underestimated for developments designed prior to 2016. Similarly, what we estimate now as a storm event with a return period of 1 in 100 years, could potentially be reclassified as the 1 in 50 years storm event in the near future. So, what we consider as an adequate design now, could be considered as inadequate in the near future,’ he warns.

With so much uncertainty, Linardatos is cautious about relying on flood prevention technology other than to protect existing buildings and communities: ‘Locating new developments in areas which are not at risk of flooding is the most effective approach for managing flood risk, and designers should aim to direct water away from buildings rather than designing buildings to withstand flood water, as if flood defences fail then it’s a threat to life. I was involved in the design of flood mitigation measures for properties that were affected from the summer 2021 floods in London. Water inundated some properties from the main entrances, but still some homeowners were not willing to replace their timber doors with UPVC flood doors. Similarly, it is difficult to stop homeowners from replacing flood doors and windows with products of their choice at a later date, so it would be unsafe to design new developments or buildings that rely upon flood resistance and resilience measures.’

He has already seen a change in direction in the UK. ‘Historically, the priority of flooding related policy in the UK was to ‘keep the water out’. This has now changed, and the focus is on ‘making space for water’, aiming to direct flood water in open spaces and away from buildings rather than defending against it.’ For example, Price & Myers worked on the Thames Hospice in Maidenhead, next to Bray Lake and close to The Cut canal and the River Thames. The solution was to artificially raise the levels of the buildings to above the 100-year plus 70% climate change allowance storm event, while at the same time dropping the levels in other areas of the site to provide a safe, non-damaging place for water to go. ‘Raising the ground levels to protect new buildings from flooding can result in flood water displacement elsewhere, so proposed development should aim to create more space for flood water storage in comparison with the existing situation.’

Another option for rising river and tidal levels is buildings that rise with the water, such as Brockholes Visitors Centre by the river Ribble in Lancashire, where Price & Myers worked on a waterside building by Adam Khan Architects that could rise on a pontoon. Taken to its logical conclusion, completely floating buildings, such as the Floating Dairy Farm by Goldsmith, moored in Rotterdam Harbour, offer a resilient option for a more watery future, using modern technology and materials to create a 21st-century version of the floating villages seen in cultures from Bangladesh to China.

It is in cities – where the UK government, for example, wants to concentrate on brownfield housebuilding – that the challenges of dealing with flood water are most acute, says Linardatos: ‘The value of the land and the construction cost of new projects in urbanised areas lead to high-density developments where the available space for floodwater management is compromised. Public sewers are usually overloaded and unable to manage run-off from the catchment areas that they serve, and there is no clear strategy for tackling the flood risk from surface water.’ While planning rules for new developments have strict water management policies, infills in urban areas often divert even more water into impermeable city streets, making flash flooding even more likely.

There are viable solutions, says Linardatos, talking about the benefits of increasing green spaces to form ‘sponge cities’ – an idea that was largely rejected in London. ‘Large plots of high-value land would need to be sacrificed in order to form the open spaces and wetlands for flood water storage,’ he says. ‘This may have been one of the reasons that Thames Tideway Tunnel was seen as the preferred solution, instead of the transformation of London to a sponge city, when options for controlling the contamination from sewers in the River Thames were assessed. The new super sewer aims to resolve one of the consequences of flooding from sewers rather than tackling the problem at its root. When HS2 came along, the government bought land and gave compensation – we’d have to do the same to create a sponge city, but the value of the land would make it so expensive.’

The idea has been successfully adopted elsewhere, however, such as the Shenzhen Guanlan Riverside Plaza in China, which won World Architecture Festival’s Landscape of the Year 2024 award. Here, a mix of hidden underground rainwater storage and a rainwater garden provides a green lung in the city while preventing flooding. ‘Green spaces that are designed to control floodwater in extreme storm events can also deliver other benefits, from cleaner air to wildlife habitat,’ notes Linardatos.

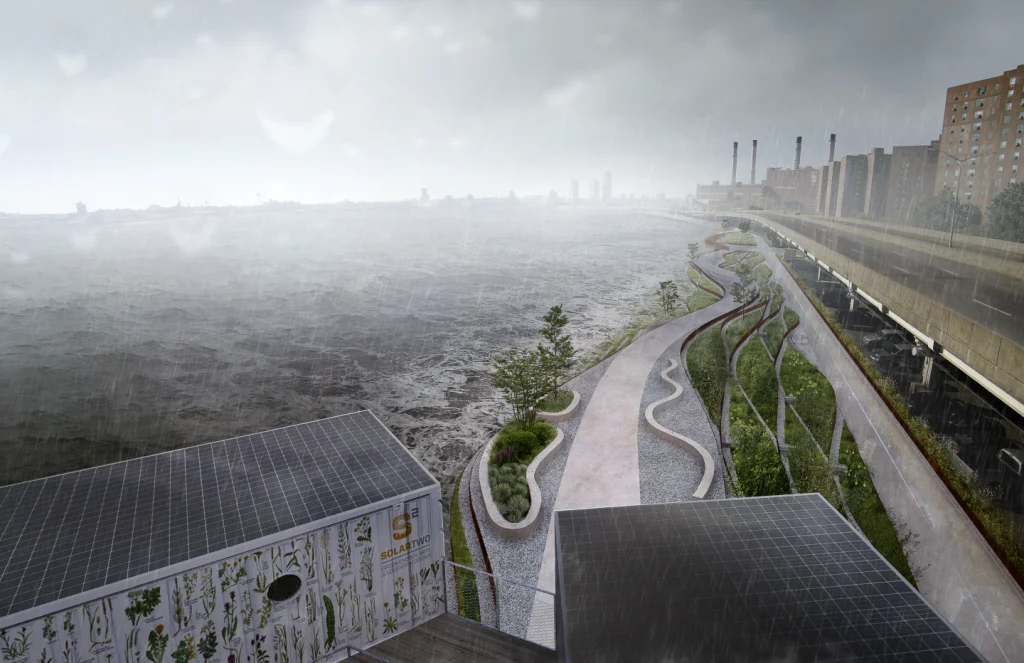

Parks and public spaces can also be used to protect communities from extreme tides and rising sea levels, without the need for depressing concrete fortifications. Fish Tail park in Nanching, where Turenscape created a 126-acre park on the flood plain of the Yangtze River, regulates storm water, provides habitat for wildlife, and offers an array of recreational opportunities. On a larger scale, The BIG U project by BIG, the first phase of which was completed last year, came out of a competition from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to find design solutions that would protect New York from events like Hurricane Sandy, which flooded large areas of the city, causing dozens of deaths and $42bn in damage. The resulting project encompasses a programme of works that will protect the city, with raised parkland alongside floodwalls and gates. Not only does it protect some of the poorest areas of the city as a priority, but the resulting green spaces, such as Asser Levy Playground, Stuyvesant Cove Park and Battery Park, provide much-needed new public spaces. Architect Brian Penschow, past president of the American Institute of Architect’s New Jersey chapter, has seen the improvements taking shape: ‘The best projects are taking care of people, like Battery Park in New York. With climate change, we have a problem not just with buildings but with society itself, as it’s the poorest, the displaced and the most vulnerable who suffer most in extreme conditions.’

Winds of change

Alongside surface water flooding, the peril of high winds is also increasing. HOK’s 12-storey Luminary Hotel in Fort Myers opened in September 2020 and was designed for extreme hurricane conditions. It’s set on an elevated plinth, with a simple design without alcoves or recesses to avoid wind forces creating additional stress, along with a slight bend in its massing for strength and stability. Just two years later, Hurricane Ian put it to the test with winds that caused $112bn of damage and killed 150 people, but left the hotel unscathed and able to become a centre for rescue efforts.

On a more domestic scale, in 2018, Florida was battered by Hurricane Michael, which destroyed every single beachfront home except the Sand Palace, designed by a local doctor with 40ft pilings and 30cm-thick reinforced concrete walls, far exceeding what building codes demanded. ‘We can build to withstand a tornado,’ says Penschow, ‘but hardly anybody does it in the US because it would be five or six times the cost in construction, and while homeowners want things to be more robust, developers want low regulations. Codes are a political process and they settle for what is really the bare minimum.’

Allan Gibson is marketing segment manager at Kuraray Europe, which developed the Trosifol SentryGlas hurricaneproof glass used in the Sand Palace, as well as projects as diverse as the River Kendal flood protection scheme and the Porsche Design Tower in Miami. ‘While current codes provide a strong foundation, they can often lag behind the realities of the changing climate,’ he warns. ‘For instance, extreme temperatures, wind loads and projectile impacts are becoming more frequent, yet building codes in some areas remain reactive rather than proactive. There is a pressing need for more frequent updates and a harmonisation in standards globally to ensure they reflect evolving climate risks.’

Yet not all areas are equally affected by climate change. Mitchell notes: ‘In the US, the response to climate change in Los Angeles is very different than the appropriate response in Miami or New York. Nationalised building codes that target local conditions and are updated as climate change occurs are the most effective approach to designing for climate change, as codes are enforceable by law and cannot be circumvented for cost savings or construction convenience.’

In some parts of the world building codes are political hot potatoes. According to HOK’s Landreneau: ‘Codes do change, they are updated every three years, but we are not building for the events we have in front of us.’ When she sat on an energy codes development committee she was dismayed to find heavy representation from housebuilders and interference from a gas association, which eventually sued to get the provisions of electrification that had been placed in the code overturned. ‘Developers say they can’t afford to build better, but we can’t afford not to. We are not going to air-condition our way out of climate change,’ she says.

Brian Penschow believes that architects need to hold developers – and themselves – to account: ‘We get stuck in the mindset that this is the way the world is – we have produced so much poor architecture, and it’s really a product of capitalism. Developers are monetised to build things cheap and less sustainable – building more sustainably pushes the costs up front, but developers prefer to build cheaply and transfer the costs to the end user, the owner. As architects we need to be more willing to say ‘no’ to the ugly and the cheap.

‘We like to think our way out of a problem – the more difficult the problem, the more intellectual resources and technical knowledge we need to solve it, but that’s not true in this case. The answers and techniques are already there and in use around the world – like building on stilts to prevent flooding, or building earth berms for example. As architects we need to step away from hubris and building glorious monuments to ourselves and we need to get back to what’s essential.’

In the end, says Adam Mitchell at CambridgeSeven, it’s everyone’s responsibility to persuade cost-cutting clients that resilience against climate change is worth investing in: ‘It is essential that design professionals, as leaders, take a central role in educating our clients and the wider public about the necessity to design for our new climate, for resilience to increasing hazards, and the reduction and eventual elimination of fossil fuel use.’

PROJECT

THE HÔTEL KSAR ROUGE

The Hôtel Ksar Rouge in Tozeur embraces the wisdom of vernacular architecture, combining patios, mud walls, graceful vaults, and cooling fountains. Light-filtering screens create a subtle interplay of light and shadow. These elements blend timeless tradition with contemporary elegance, resulting in a sanctuary of fresh, clean air that rises above the desert heat.

Architect Tarak Ben Miled International

PROJECT

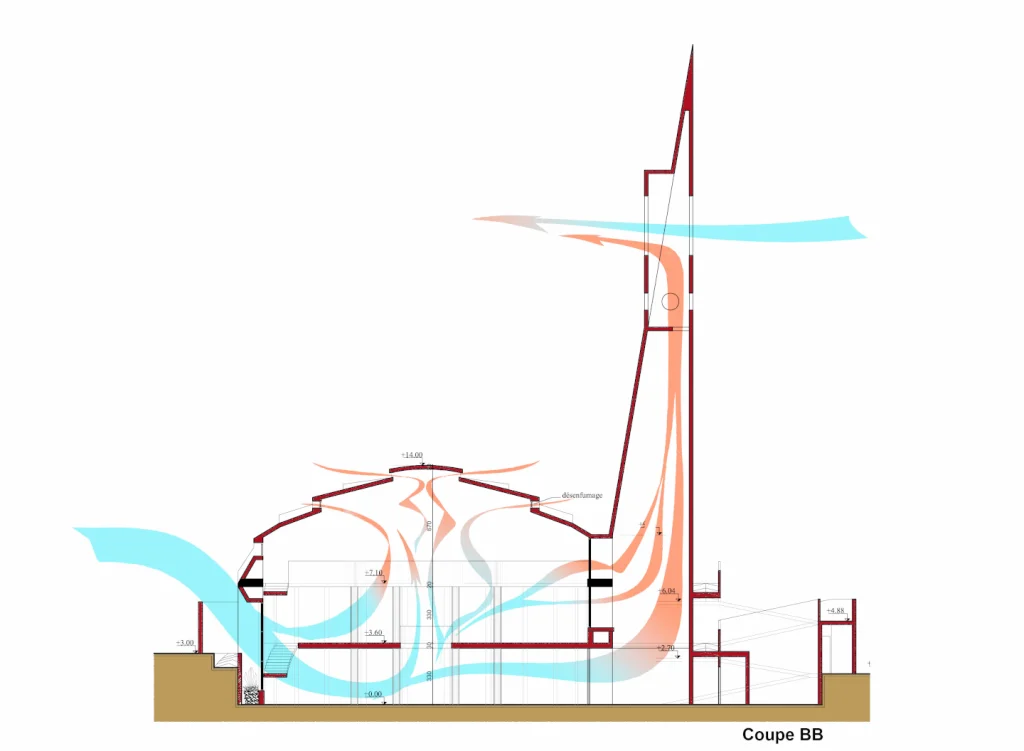

IBRAHIM EL KHALIL MOSQUE

Ibrahim El Khalil Mosque in Tunis features garden-level openings to draw air in through purifying, humidity-regulating plantings. The circular form creates natural convection through the whole volume, and the funnel-shaped minaret draws warm air out using the Venturi effect.

Architect Lotfi Rejeb – Studiarchi International

PROJECT

CORAZÓN DEL VALLE

Award-winning Corazón del Valle, a housing development in the LA neighbourhood of Panorama City, comprises 180 homes for those on low incomes. It features three curved masses, carefully designed to funnel the prevailing winds into the courtyard, gardens and homes, with shade structures and plantings for additional cooling effects, plus a 288-panel solar array and greywater reclamation system.

Architect Perkins & Will

Client Holos Communities

PROJECT

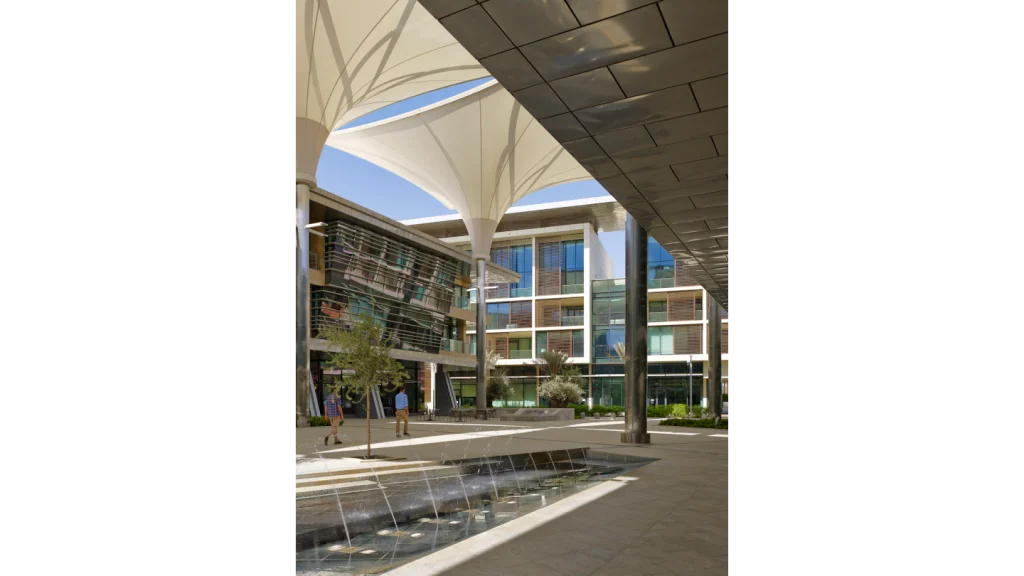

AYLA GOLF CLUBHOUSE

This clubhouse in Aqaba, Jordan, is part of a mixed-use resort with a championship golf course designed to be one of the most eco-friendly in the world. Openings capture coastal breezes, and sunlight is filtered through perforated Corten steel screens, similar to the traditional Arabic mashrabiya. Inspired by dunes and Bedouin tents, the building has a shell of shotcrete made with soil from the site, doused in local minerals and pigments by an Aqaba artist.

Architect Oppenheim Architecture

Client Ayla Oasis Development Company

Local architect Darb Architects and Engineers

General contractor Modern Tech Construction

PROJECT

COLLEGE OF LIFE SCIENCES

The multi-award-winning college, part of a new university on the fringe of Kuwait City, was designed as a response to the harsh desert conditions experienced on the Arabian Peninsula. Heat, dry air and the solar glare were managed through the use of mashrabiya, reimagined to provide protection against heat gain, but also to redirect views from the building and allow the soft, even light from the north. The façades were tilted outward to self-shade the interior and allow users to occupy more of the floor plate, while two large atria act like heat chimneys, passively drawing cool air up through the building.

Architect CambridgeSeven

Client Kuwait University

Consultant Gulf Consult

PROJECT

THE KING ABDULLAH PETROLEUM STUDIES AND RESEARCH CENTRE

The King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Centre (KAPSARC) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, is home to hundreds of international researchers in energy studies and their families. The community is planned around a dry riverbed providing mitigation for storm water, transformed into a linear park and central oasis, with indigenous, drought-tolerant plants irrigated with recycled water. Several of the sculptural, stainless-steel roofs extend toward the park to create flowing shade canopies, and streets are designed for air flow and cooled with fountains. Of the 191 homes, 188 were awarded LEED Gold certification.

Architect HOK

Client KAPSARC

PROJECT

THE THAMES HOSPICE

The Thames Hospice in Maidenhead was surrounded by a large lake, a canal and the River Thames, on a site that was partially high-risk Flood Zone 3 and partially medium-risk Zone 2. The ground under the hospice buildings was raised out of reach of foreseeable future flooding, while a surface water drainage system included large attenuation tanks located beneath the car parking areas, which have been designed with permeable surfacing to provide a safe place for water to go.

Engineer Price & Myers

Client Thames Hospice

Architect KKE Architects

PROJECT

BROCKHOLES VISITORS CENTRE

The BREEAM Outstanding accredited Brockholes Visitors Centre, in the floodplain of the River Ribble in Lancashire, sits on a floating pontoon held in place by steel posts, enabling it to raise and lower with water levels, protecting it from flooding while enabling visitors to get close to the area’s wildlife.

Engineer Price & Myers

Client Lancashire Wildlife Trust

Architect Adam Khan Architects

PROJECT

THE FLOATING DAIRY FARM

The Floating Dairy Farm is a self-sufficient floating farm building, moored in Rotterdam, which brings farming into the city. The covered ‘cow garden’ houses up to 40 animals, whose milk can be processed and made into yoghurt on an upper factory floor. Centrally placed ‘green columns’ provide natural cooling.

Architect Goldsmith

Client Floating Farm Holding BV

Engineering Alcomtec

PROJECT

SHENZHEN GUANLAN RIVERSIDE PLAZA

Transforming a concrete plaza into a green park, the regeneration of Shenzhen Guanlan Riverside Plaza won the World Architecture Festival Landscape of the Year 2024. The tree coverage has been increased from 30% to 65%, alleviating the urban heat island effect, with 200 native evergreen trees providing year-round shade in the hot climate of southern China. The multifunctional fountain in the centre of the plaza also helps to cool down the space, which comes into its own during heavy rainfall, when a 300m2 rain garden collects rainwater, with the excess moved into a large underground storage system, from where it is purified and used for irrigation and surface cleaning.

Architect Lay-Out Planning Consultants

Client Shenzhen Longhua District Urban Management

PROJECT

FISH TAIL PARK

Fish Tail park in Nanching is a new 126-acre park on the flood plain of the Yangtze River. Flooding and urban inundation during the monsoon season has been a chronic challenge for Nanching, worsening with climate change and rapid development. The park includes a lake able to accommodate a 2.0m water-level rise and store a million cubic metres of storm water. Much of the park, from the central forest with marshland trees to the boardwalk and street furniture is designed to be safely submerged during 20-year flood events and annual monsoon floods.

Architect Turenscape

Client Nanchang Gaoxin Real Estate Investment Co

PROJECT

MANHATTAN FLOOD DEFENCE

During Hurricane Sandy in 2012, 69,000 New York homes were flooded. After, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development launched a Rebuild by Design competition for innovative solutions, and architect Bjarke Ingels designed a scheme, the initial stages of which completed last year, that used new riverside parks to discreetly protect the city. The key to the project, Ingels stated, was that people will not notice the flood barrier: ‘You won’t see it as a flood wall that separates the life of the city from the water. When you go there you’ll see landscape, you’ll see pavilions, but all of this will secretly be the infrastructure that protects Manhattan from flooding.’ His first priority was to protect Manhattan’s East Side, which is home to more than 110,000 low-income residents. The project strengthens the coastline while re-establishing public space and improving waterfront accessibility.

Architect Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG)

Client City of New York

PROJECT

THE LUMINARY HOTEL

When Hurricane Ian battered Fort Myers with 150mph winds and a storm surge flooding much of the town, the resilient architecture of the Luminary Hotel meant that it was undamaged and able to function as an emergency response centre. The hotel was built on a plinth, nearly 3.0m higher than ground level, so no water entered the building, and its design, with a slight bend in its massing, gave it additional stability without using any extra materials. The simple frontage, without alcoves or recessed, prevented the wind from putting additional stress on the building, while hurricane-proof glass stood firm against debris.

Architect HOK

Client Marriott Hotels