‘SOMETHING WONDERFUL is happening’, posters promoting the National Gallery in London declared, and this was true. Only it was happening in Paris.

On show at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in the Bois de Boulogne, the building of glass sails designed by Frank Gehry, is the biggestever Hockney exhibition. With 456 works, David Hockney 25 is one enormous splash. Hockney writ large. No expense has been spared to bring it all together – transport and insurance costs would be hard for any other institution to shoulder. Hockney’s greatest hits from 1955 onwards that he personally selected are here together with most of the work produced in the past 25 years. We travel with him from Bradford, to London, to California, back to Yorkshire, to Normandy, and finally back to London. It is an exercise in self-revelation, a hit not of nostalgia but of emotion for the artist and for visitors. This is the authorised version: he does not expect to witness a similar show again.

Commenting on the exhibition, Hockney said: ‘When I started preparing for this exhibition almost two years ago, I felt it was important to review several bodies of work through the years to curate a representative selection for the public. The show means an enormous amount to me because it is the largest I have ever had… I have chosen to concentrate on the past 25 years, inspired by the time I have spent in Yorkshire, Los Angeles, Normandy and London. Some of my most recent paintings are included, and I do think it is a very enjoyable and visually interesting survey of works.

‘Not many artists have been drawing similar themes and the same people for more than 60 years. What I am trying to do is to bring people closer to something, because art is about sharing. You wouldn’t be an artist unless you wanted to share an experience, a thought.’

‘No English artist has ever been as popular in his own time, with as many people, in as many places.’ This was art critic Robert Hughes’s view in 1988 and it is still true of Hockney today. After a lifetime of unshakeable self-belief, the golden boy of British art has maintained the kind of celebrity usually reserved for film stars, but rarely visited upon serious artists. With his hair and his glasses and his voice the fame machinery kicks in. It has never been turned off. And no one seems to begrudge the artist his success. He is a national favourite. His talent and his unflagging, indefatigable industry, his technical versatility and immense skill, as printmaker, photographer, set-designer, draughtsman, theorist… all alongside being a great painter. He is a userfriendly modernist, an unthreatening prince of visual charm, always displaying a perfect alliance of form and content.

There are red rooms, and cream rooms, blue rooms, green rooms, yellow rooms and plenty more. Marco Palmieri’s studio in Milan was responsible for the exhibition design. ‘To define the wall colours for the Fondation’s galleries, I selected tones outside David Hockney’s typical colour palette – hues that could visually interact with his works through assonance. These are deep, subdued shades – intentionally muted and complex, designed to emphasise, by contrast, the expressive power of his art: a soft yet intense red, a dark green with bluish undertones, and a rich but restrained yellow. My aim was to ensure the artworks remained central, avoiding a neutral or conventional display. I wanted to highlight the separation between the visual language of his paintings and the surrounding space.’

However brightly the rooms are painted, there is a problem with being involved in curating your own show: it is almost inevitable that you include too much. Plus, there is a sense that here is an older man in conversation with his younger self. Nevertheless, it is a show of encounters. He is the man in the crowd, who sees everything, and has an eye for every detail, capturing the animating force of life – in the faces of friends and loved ones, in a blossoming tree, a change of season or a night sky. And it is memory-making: about stockpiling the moments that define an era. Fashions fade, Hockney remains.

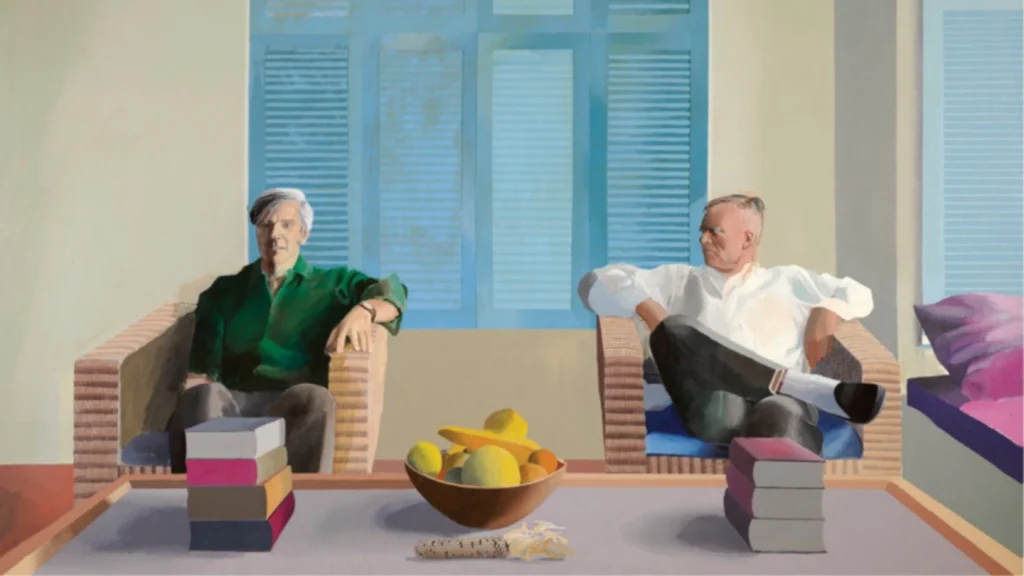

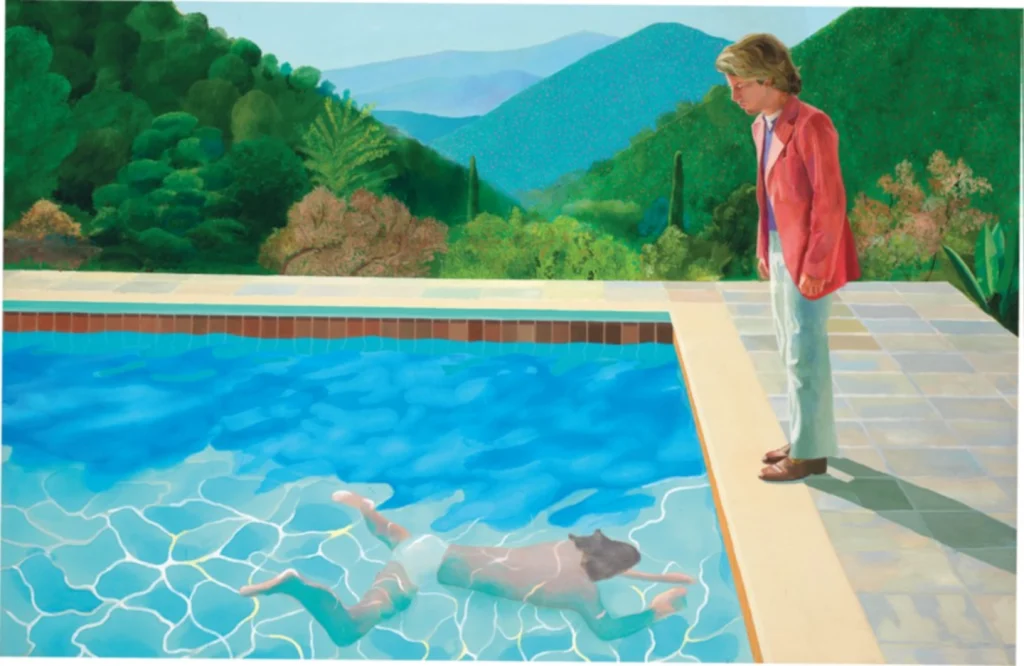

Auden said in a poem about Yeats that poetry altered nothing, that all the savagery in the world would be the same if no poet had ever written. The same could be said of painting. The most important thing that art can achieve is to bring pleasure – true pleasure. And Hockney has never failed to do that. His ability to find beauty in the mundane has never deserted him. The 21st century moves to its second quarter without a sense of optimism, but we have an artist whose sense of optimism seems never to have faded, and whose ability to bring pleasure is as evident today as it was in the 1950s and 1960s. The gritty integrity of his Royal College years (a mix of graffiti and a billboard-sized packet of Typhoo tea) led to instant stratospheric success that in turn gave way to a fugitive from publicity hounds; California beckoned and with it the surreal suburbia of Los Angeles – a world of paradise, and escape. Picture-perfect splashes, helically turning sprinklers against the everblue West Coast sky, affectionate double portraits, big soaring landscapes of the Hollywood hills, he takes the eye on a journey – those drive-through compositions, the canyon paintings, the multiple-view impressions of a journey. He is seemingly always on the move. It is all here in this exhibition, and that is just for starters.

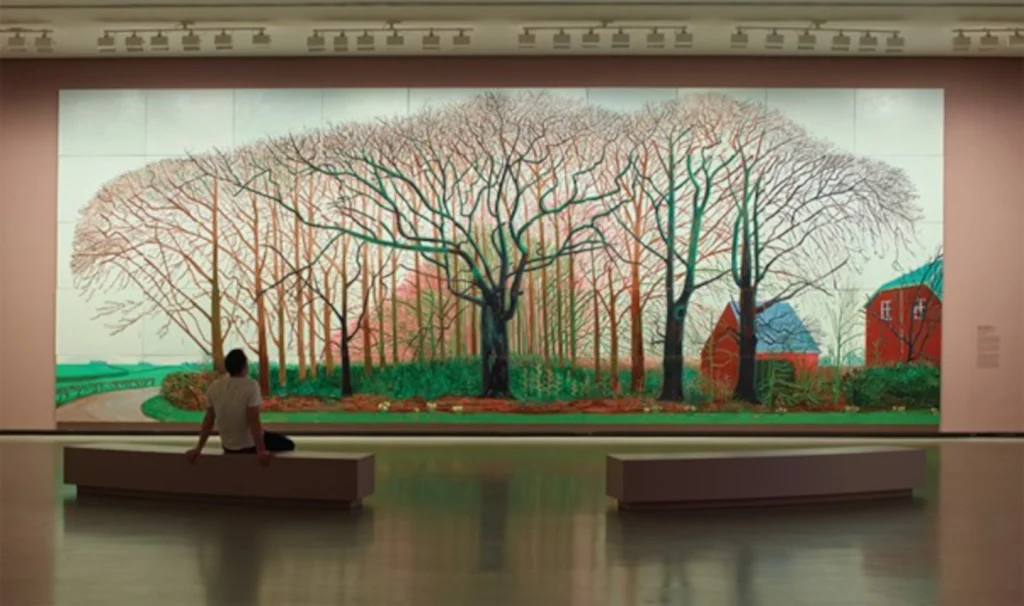

The heart of this quarter-century anniversary begins with a celebration of Yorkshire landscapes: watercolours, charcoal sketches, oils, acrylics and film, in a display of great dexterity, overheated colours, multiscreen brilliance, all searching to define a pictorial language appropriate to his home county across the seasons of the year, including a hawthorn bush spectacularly exploding into spring. Far from the vistas of A Bigger Grand Canyon (1998) Hockney explored landscape at a scale both intimate and imposing, for which he defined a new and no less effective visual language. Working en plein air, while also using photography and computers, he completed his largest work, Bigger Trees near Warter or/ ou Peinture sur le Motif pour le Nouvel Age Post-Photographique.

It was in 2018 that Hockney flew into London from LA for the inauguration of his stained-glass window in Westminster Abbey and, on an impulse, then took off for a threeday trip to France. He saw the sun rise over Le Havre, set over Honfleur, visited the Bayeux Tapestry, and then in 2019 bought an abandoned 17th-century maison à colombages complete with cider press, south of Deauville, deep in rural Normandy. And then, as pandemic lockdown restrictions left him in the Pays d’Auge with nothing to do but paint, he created what became ‘the Covid Collection’: initially 116 iPad drawings blown up to 1.5x1m inkjet prints and called at the time The Arrival of Spring, Normandy 2020. It was a different kind of mark-making. Some people were overawed, others were not so convinced.

Then there were 220 images, published as 220 for 2020 that were later combined into a continuous frieze 90m long, comparable to the Bayeux Tapestry. Among a set of iPad animations are 12 panels depicting his garden through the seasons, dawn to twilight, that unite finally into one sunburst image titled with a quotation from French writer Francois de La Rochefoucauld, Remember You Cannot Look at the Sun or Death for Very Long.

In Normandy, the artist also began a series of flower ‘portraits’: bouquets of colour presented in ornate wooden frames as if they were traditional paintings. Their arrangement, ordered daily from the florist in carefully chosen colours, never varied: a glass vase, jug or milk churn, allowing for the play of transparencies and reflections, is placed on a table covered with a checked tablecloth and stands out against a brown background. These are displayed next to a room of 60 elegiac portraits of friends and family, workmates, security guards, mayor, plus no less than 18 self-portraits, often self-mockery that verges on caricature.

‘Opera = collaboration = compromise – which is something I do not do,’ Hockney has stated. Yet he is a natural stage designer, and his sets and costumes are celebrated in an all-engrossing room, with a special polyphonic programme devised with 59 Studio. Whereas a set design deprived of the spectacle of performance can seem dead, here the working documents are brought alive. Hockney has always loved music, seeking to translate it into colour and form. He saw his first opera, Puccini’s La Bohème, as a child in Bradford. From the 1960s onwards, his paintings incorporated scenic elements: curtains, sets and costumed characters. In 1975, he was commissioned by the Glyndebourne Festival to design the sets and costumes for The Rake’s Progress by Stravinsky, an opera-fable inspired by William Hogarth’s engraved series of the same name. The musical and visual reworkings of his images for various operas conceived for the exhibition also includes his vision of The Magic Flute, Tristan und Isolde, Turandot, and Die Frau ohne Schatten.

His intellectual restlessness and addiction to ideas have been expanded into writing controversial books (Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters), a taste for scholarship that has always been far more serious than mere distraction. Much has been written about Hockney’s view of art history and how artists may have used technical aids to deliver their paintings. His approach is rather like his own version of art historian Aby Warburg’s credo of Kulturwissenschaft, a scientific approach to cultural studies that turned on connections and juxtapositions. Two whole walls of interlocking and overlapping images at the Fondation Louis Vuitton attest to this continued fascination, from Albrecht Durer onwards, via Caravaggio and Jan Vermeer, to discover how artists made their art, an obsession exemplified by two recent particularly enigmatic paintings inspired by Edvard Munch and William Blake in which astronomy, history and geography cross paths with spirituality. Both called Less Is Known than People Think they pick up on Hockney’s abiding interest in the complexity that lies behind the apparent simplicity of some of his favourite artists: Monet or Van Gogh, Picasso or Fra Angelico, or Claude Lorrain, whose The Sermon on the Mount (c1656) inspired him to make a series of paintings culminating in a vast rendition of the 17th-century masterpiece that he entitled, ironically, A Bigger Message. In his most recent self-portrait, Play within a Play within a Play and Me with a Cigarette, Hockney has depicted himself sitting in his garden, together with a collage of the work in progress, and daffodils announcing the arrival of spring.

Roger Shattuck’s Proust’s Binoculars was the starting point for Hockney’s photographic collages and multiple viewpoint-painted images. It gave him the initiative. Proust was writing at a time when Jacques-Henri Lartigue was beginning to take his famous instantanées in the Bois de Boulogne, snapshots that assumed great importance in the writer’s thinking, and a time in which Hockney was later to immerse himself, living in Paris from 1973 to 1978. Proust distinguished three ways of seeing or recreating the world: the cinematic that produced the effect of motion; the montage that produced disparity and contradiction interrupting the continuity of experience; and the third principle – which held Hockney’s particular attention – the stereoscopic, which abandoned the portrayal of motion to establish a form of arrest that resists time, images sufficiently different from one another that nevertheless give the effect of continuous motion, a principle that allows our binocular vision to hold contradictory aspects of things in the steady perspective of recognition, of relief in time. Proust moved around the three principles in his vast novel in the quest for truth that affirmed, as Shattuck saw it, a ‘miracle of vision’.

Now, as we enter the second quarter of the 21st century, Hockney’s own miracle of vision is on show in Paris, one long journey through landscape and portraiture, from his earliest likeness of his father to his very latest works. Something wonderful has certainly happened.

The David Hockney 25 exhibition is on until 31 August. www.fondationlouisvuitton.fr