CONVERSATIONS AROUND equality and inclusivity dominate the current political and cultural arenas – often with polarising effects, as ongoing global election upheavals demonstrate. Since the #metoo and #blacklivesmatter protests, museums and galleries have done their best to create space for the necessary expansion of perspectives, to encourage debate and broaden impacts through the artists and thematic exhibitions they programme. Novelists, filmmakers and TV/radio/podcast programmers have done likewise. But encounters with this kind of enrichment always happen behind closed doors and for fairly self-selecting audiences. How do we transport some of this inclusivity into the open?

Designer and artist Adam Nathaniel Furman is on a mission to bring the kind of emotionality and colour that they feel typifies a queer perspective into public spaces. Since 2023, Furman’s sensuous, colourful and playful designs have appeared as permanent enhancements in the public realm, from Croydon to Bristol (see case study).

I first spoke with them in autumn 2023, when Kew Gardens staged an informative and colourful show about the decidedly non-binary, gender-fluid world of plants, Queer Nature, with accompanying art works. The depth of Furman’s knowledge about gender and design was enlightening. The insights they shared, for example, around Victorian interior design and the symbols that have, historically, been associated with queer communities, were infused into Furman’s richly patterned silk fabric that hung from Kew Gardens’ greenhouse rafters to create a lushly immersive space.

Says Furman: ‘I see all those deeply sensual decorative domestic interiors of the late 19th century as being queer, but this project is taking the way Victorian chintz is seen, bringing it into the queer context here, and designing something new within that world. The design was meant to be within the decorative aesthetic movement and tradition. It’s all based on symbolic flowers from that period: pansies, lavender, green carnations, tulips; flowers that have been very important symbolically for the queer community from the mid 19th century on. I have used the scrolling acanthus as a matrix for how it co-ordinates as a pattern. Referencing Graeco-Roman history is also really important for the gay male community: there was this idea of hiding in plain sight by justifying your interest in sophisticated Graeco- Roman history. Demonstrating a love of classicism was effectively a way of allowing yourself to be gay and these motifs became very important for queer culture, from the 17th century to mid 19th.’

For Furman, who spent the late 1980s/ early 1990s as a budding architect in the then predominantly male, chauvinistic British architecture scene, working with the Kew Gardens curatorial team on this project was a breakthrough moment. ‘For most of my career I’ve absolutely hidden the queer parts of my work. And then people haven’t been interested in it. So to have a team of really knowledgeable people who know about the subject from their own perspective approach me and then be able to have really in-depth conversations… it’s not something I’ve really experienced before apart from when I was doing the NGV (National Galleries of Victoria, 2020 Triennial) installation in Melbourne. It was just so nice.’

With the Kew commission, Furman says: ‘The silk fabric and the patterns are an enjoyable twist on how people tend to think about Victorian decorative culture as old-fashioned and fuddy-duddy, whereas for me, it’s deeply radical in terms of sexual liberation politics. The domestic, in the 19th century, was a site of great tension and anxiety – as was the decorative.’ Flamboyance in texture and hue was ‘regarded as… undermining the masculine Spartan creed of the British male that was integral to going out and running the empire. It was seen as feminine and queer. The rhetoric of justification to sideline anything seen as non-masculine was never just against queers, or just against women, it was always against both.’*

In the light of Furman’s insights, the preponderance of boring, colourless/bronze male statuary (by male sculptors) adorning prominent sites of public space seems even more strategically patriarchal: trumpeting male military achievements (or on the part of the general public/soldiers, sacrifice) and economic success (regardless of who was exploited to achieve it). You could say it’s all so last century except, actually, it was the prevailing attitude even into this century, until very recently. Curator Claire Mander is on a mission of her own to rectify the imbalance of visible women artists in the public realm. Seizing an underutilised public ‘garden’ (albeit free of grass or plants) above Temple Tube on the London Underground, she opened The Artist’s Garden in 2021, determined to showcase women artists’ work. The first exhibition featured British-Ugandan artist Lakwena Maciver, with a technicolour vision of Paradise, in ceramic tiles. In 2024, a new group show was unveiled here, also featuring all women artists (see case study).

Maciver grew up between London and East Africa and has sought to articulate geographic and cultural diversity through graphics and colour since 2009, when she graduated in graphic design from the London College of Communications. An international following sprang from her 2013 mural I Remember Paradise, unveiled at a street art festival in Miami. Since then her installations have appeared at Tate Modern, Somerset House and the Southbank Centre in London, as well as a juvenile detention centre (the mural Still I Rise, 2017) in Arkansas, and a monastery in Vienna. In a 2022 interview, she told Studio International: ‘I’m interested in the things that people interact with in their everyday lives, like music and fashion – things that you don’t have to go into a special space like a gallery to see. I like that murals are usually very accessible and there’s no exclusivity. When I was studying graphic design, I looked at Diego Rivera’s murals and I was drawn to his democratic, anti-elitist approach – the idea of murals being for the people.’

She was an inspired pick as collaborative partner for architecture practice IF_DO when it entered a competition to create a prominent landmark disguising a new electricity substation in Brent Cross, as part of developer Related Argent’s ambition to turn an unlovely neighbourhood into something more atmospheric and appealing. It won an FX Award in 2024 for Outside Space. Both in the vibrant palette and its dynamic form, it says to current and would-be residents of this rapidly evolving neighbourhood that global perspectives – and people – are welcome (see ‘Brent Cross’ case study).

Thomas Bryans, IF_DO co-director, tells FX: ‘Architects are often quite wary of colour, but it’s something we are embracing more and more. Colour brings a lot of joy, and in architecture joy really matters – especially in the urban realm, and the British urban realm in particular, which is often grey skies and grey buildings.’

Bryans is a big fan of Furman as well as Yinka Ilori, whose gorgeous sorbet-bright palette has breathed a distinctive European/African aesthetic into public structures and brand experiences around London and further afield. Ilori first made a splash with his summer pavilion, The Colour Palace, which landed in the gardens of Dulwich Picture Gallery (DPG) in 2019. A commission co-created between DPG and the London Festival of Architecture, its first incarnation was designed by the then fledgeling IF_DO back in 2017. The success of these temporary projects has inspired the team at DPG to create a sculpture garden in what was formerly a neglected grassy space. And soon a new, permanent, interactive art work will bring a family- and diversity-friendly spirit to this iconic, Sir John Soane-designed cultural landmark. It will open in early 2026 (see ‘Dulwich Picture Gallery playable sculpture’ case study).

This flourishing of inclusivity in the public realm has been a long time coming. Diversity is not just about canvassing opinions or hosting consultations where citizens get some small say over an architect’s preselected options. Bryans is clear that by choosing to work with a broader spectrum of architecture and design teams in the first place, ‘you can articulate that diversity through what is built and what is realised. With Related Argent, I think they were very conscious of a desire to bring diversity to that site.’

Pedro Gil, founder and director of Studio Gil, has been championing the inclusion of perspectives and design sensibilities from the global south in London projects that impact heavily on these communities. This advocacy was sparked in 2009 by the massive redevelopment of Elephant & Castle, where there is a strong Latin American contingent. Gil – whose parents are Colombian – made use of his architectural training to support local Latin American businesses as developer Lendlease began dismantling decades-old housing and retail infrastructure and reshaping the neighbourhood with its aspirational park landscapes, luxury apartment blocks and unaffordable townhouses. Says Gil: ‘The practice has been born out of a desire to give a voice to those that don’t typically have a voice in these built environment spaces. The Latin American community in London is not often recognised. We are the second fastest-growing ethnic group in the UK second to people of Chinese heritage and comparable in size to the substantial Nigerian and Pakistani communities. We create jobs, we are entrepreneurial, we pay taxes; 50% of Latin Americans in the UK are university educated. Yet we don’t have any assets. There are zero buildings in Latin American ownership. Plenty of leases. But when it comes to owning a cultural community asset, zero. I’ve gone with my instincts about where I feel I can add value.’

Gil assisted many of those Latin Americanowned business that could afford to relocate further south, to the Old Kent Road and the Walworth Road.

And since then, Studio Gil has become a sought-after design partner and advocate in projects where communities or charities are seeking to preserve or create a space that celebrates their culture and identity. Says Gil: ‘Because of the nature of community and charity work, they are often not well-funded, but they have very clear vision, very clear needs, and very clear outputs. Where my studio gets involved is how we translate that into space, and then we produce material that they can then use to fundraise. Around 80% of the work we do doesn’t have funding when we come on board. We lend our credibility to the organisation, so that now, the Greater London Authority or National Lottery heritage fund pay attention when we say we’re involved in something. Because they know what we do. While co-design and participation has become fashionable, we have been doing it from the outset.’

Through Studio Gil’s advocacy and research, Southwark is now ‘interested in developing a Latin American cultural centre, and I’m talking to Haringey about something similar,’ says Gil. Also emerging are plans for a new teenage female-centric outdoor recreational space in the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park (see ‘A park for teenage girls’ case study), design, details of which will be released in early 2025. Most significantly, the London Legacy Development Corporation’s intensive ‘co-clienting’ process (going way beyond co-design, actually bringing stakeholders in on all decisions) is set to become a blueprint for future public space developments, setting a precedent for designing for marginalised communities everywhere.

CASE STUDY

ATELIER ANF

Around the time of launching an immersive, gender-inclusive space to frame a moment for peace and video testimonials at Kew Gardens’ Queer Nature exhibition (autumn 2023), Adam Nathaniel Furman (of Atelier ANF) became the go-to designer for urban realm and public art projects that banish the prevailing palette of concrete, steel, glass and greyness. Furman’s ceramic tunnel beneath a huge, phallic skyscraper in Croydon is a case in point. Dubbed by the artist as ‘a porcelain palace for the people’, Croydon Colonnade consists of 16 columns, 25ft high, and several walls clad in three-dimensional, handmade porcelain tiles. These richly textured tiles – each bearing the marks of its maker – fade from white to blue along a shifting gradient as you wind your way through this loggia. References included Croydon’s brutalist tower blocks as well as the restoration of Durham Cathedral by that pioneer of the Victorian-Gothic style, Sir George Gilbert Scott, who also designed several Croydon churches. The Durham reference is seen in the rich optical effects achieved by varying two ceramic patterns, one inboard and the other outboard, across the façade, as is seen on Durham’s stonework.

In Paddington, a 160ft-long artwork, titled Abundance, extends, concertina-style, to greet passengers entering or leaving the station – now an even busier London transport hub since the opening of the Elizabeth Line. Inspired by origami, it comprises metal sheets of the type typically found on construction sites, placed diagonally to enrich the experience of moving past them. The wall hugs the amphitheatre at the heart of Paddington Central, and Furman hoped this work’s ‘sensual and polychromatic’ sensibility will ‘celebrate inclusivity and promote well-being.’

Atelier ANF has also completed public realm and public art enhancements in Bristol (A Quilt for Bristol, made from pool tiles, which decorates a pedestrian underpass) and, in summer 2024 a flamboyant, 57m glass mosaic at London Bridge station, which pays tribute to Eduardo Paolozzi’s now destroyed mosaics in Tottenham Court Road underground station. Furman says Paolozzi’s rare moment of colour and exuberance made this an iconic meeting point for London’s LGBTQ+ community, through the 1970s and 1980s, when spaces above ground were less than safe. The London Bridge work, called In a River A Thousand Streams, references both the multiplicity and multinationalism of London’s residents and the many who came together to help create it. The designs were evolved with local residents who attended workshops, and more than 70 volunteers helped in its construction (resulting in over 250,000 glass pieces), at the London School of Mosaic’s (LSoM) Camden school.

CASE STUDY

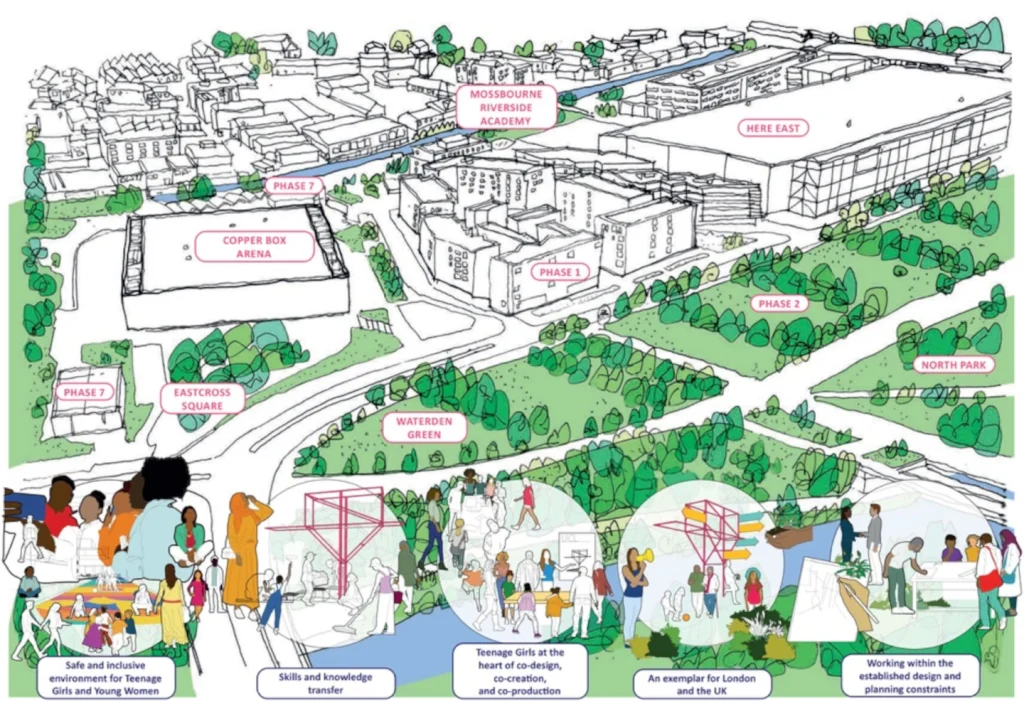

A PARK FOR TEENAGE GIRLS

Waterden Green Space is set to be a radical re-imagining of recreational public space in the emerging East Wick neighbourhood within Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, designed to be safe and appealing primarily to teenage girls. As part of London Legacy Development Corporation’s (LLDC) commitment to gender-inclusive public spaces, Studio Gil were appointed as lead consultants. Along with the charity Make Space for Girls, they have steered workshops with local residents aged 12-19 and representatives from east London’s Elevate Youth Voice collective, to ensure that the design meets all their criteria for flexibility, inclusivity and female-centred design.

A report and methodology has been published and used to inform the brief. The LLDC’s co-clienting approach, which integrates members of the engagement group into the core client team, ensures that these youth representatives are present at all key decision-making moments. Care has also been taken to ensure the various design teams include members of the global majority, which includes Studio Gil, Black Females in Architecture (engagement leads), Untitled Practice (landscape architects), Simple Works (structural engineers) and Light Follows Behaviour (lighting designers).

As for the brief, the instruction is for the design to comprise four zones or ‘pods’ that allow for a number of different teen-focused activities. There should be a mixture of covered and open-air spaces to allow for activities in bad weather. Lighting and materials have been chosen to make women feel safe and welcome.

Pedro Gil, founder and director of Studio Gil, says: ‘Psychology is part of it. Inclusivity is another. Secure by design is something else. We’re playing with all these different aspects.’ Gil hopes the final designs will accommodate both the younger girls’ desire to inspire play and the older girls’ requirement for varied social spaces. Gil also hopes to make the space inter-generational – relatives, friends and family should feel equally welcome. ‘We as a practice are also very interested in inter-generational play – it shouldn’t just be for young people or children. To some cultures around the world play is a very valued commodity.’

Client LLDC

Design teams Studio Gil Black Females in Architecture, Untitled Practice, Simple Works and Light Follows Behaviour

Delivery 2025

CASE STUDY

THE ARTIST’S GARDEN

Claire Mander, founder and director of the COLAB (a charity dedicated to bringing female artists’ work into public space), first spotted a plinth-like paved space above Temple Tube when studying at the Courtauld. She saw its potential as a public art space and launched its first outing in 2021, as a Covid-friendly gathering space, with the floor drenched in the colourful patterning of British-Ugandan artist Lakwena Mciver. Says Mander: ‘The idea is to spot a woman with talent or promise or interest in making work for the outdoors, and helping her through demystifying the process: how to present things to structural engineers, how to get through the planning process, how to communicate with the public.’ In 2024, the first group show opened, featuring work from nine female artists: Rong Bao, Candida Powell-Williams, Alice Wilson, Lucy Gregory, LR Vandy, Frances Richardson, Holly Stevenson, Olivia Bax, and Virginia Overton. Vivid and colourful, the works demonstrate both enormous diversity and presence, often encouraging public interaction, from spinning a can-can cluster of legs on a pole (Gregory’s It’s All Kicking Off, 2024) or banging and stroking the chimes offered by Overton (Chime for Caro, 2022), made using Anthony Caro’s studio offcuts.

Says Mander: ‘The site (near Waterloo Bridge and the Strand) is very, very important. And the artists’ response to the site is very important. We have artists responding to the idea of the garden, or the Thames, or aspects of nature or the landscape. Or the fact that it’s a women’s space. Many people have been surprised by this exhibition. A lot of people have come and said: “I didn’t realise that it was all by women, or that women made such big things”.’

Manders, through the work on this site, as well as ongoing collaborations and projects with Yorkshire Sculpture Park and the Royal College of Art, is building a large network of women sculptors. She says: ‘What we find here is it’s a very nurturing environment for artists. Because we’ve built up this massive network of artists, both through this and our drawing residencies, people are helping each other. The artists are helping each other. They are introducing each other to their contacts. The network is growing in this powerful, exponential way.’

CASE STUDY

WOMEN’S WORK: LONDON

The Women’s Work: London campaign was the brainchild of architecture activist collective Part W, as a means of highlighting the great unsung female heroes who have played a pivotal role in the evolution of Greater London’s built environment. An open call in 2022 for suggestions of projects ranging across architecture, engineering, landscape design, planning, conservation, commissioning or construction, attracted 150 suggestions, which were whittled down to 30 by judges (including Adam Nathaniel Furman). Thirty were chosen and then, following a crowd-funding initiative, printed up into a delightful map, launched on International Women’s Day 2023.

Highlighted projects include: Boatemeh Walk and Angell Town Estate, in SW9, to honour Dora Boatemeh MBE, a resident who campaigned for and secured community-controlled redevelopment, including the choice of Anne Thorne Architects to design a new block of 18 highly sustainable lats. The Shard was chosen for the lead role that engineer Roma Agrawal played in designing the iconic spire at its top. Waterloo Bridge features: the irst predominantly concrete bridge across the Thames, it was constructed by a largely female construction team between 1939 and 1945 (during WWII, out of necessity, a workforce of some 25,000 women were employed in constructing and repairing houses, factories and infrastructure).

Out of the 600 copies printed of the map, many were distributed to schools across London, in order to assist teachers and encourage more girls and young women to consider professions in the built environment sector. Zoe Berman, one of the founders of Part W, says the project has ‘generated lots of dialogue,’ though the challenge remains to bridge the gaps in opportunity caused by structural inequalities in practice, in who and what gets published, archived and awarded prizes. The map, she says, was always just one element of a toolkit, that could be adopted and adapted to celebrate women’s achievements elsewhere.

Client Part W

Design Edit Collective

Funding Crowdfunded

CASE STUDY

BRENT CROSS

A new local landmark for residents of Brent Cross Town – one of the largest urban regeneration projects in Europe – has provided London-based artist Lakwena Maciver with the ultimate platform, as her joyful patterns and palette ripples across architects IF_ DO’s sculptural piece of infrastructure. IF_DO and Maciver joined forces to devise and pitch the project for developer Related Argent’s competition to establish a strong, inclusive and attractive identity at a key entry point to this site. The artwork – reaching up to 21m at its highest point – wraps around a new primary electrical substation, which sits next to the A406 North Circular at its junction with the M1 motorway. Adjacent to both the Thameslink railway line and the new Brent Cross West station, it is estimated that around six million people each year will see it. Maciver, whose childhood was spent between London and East Africa, had first-hand experience of the emotional clout that colour can bring to London’s uniformly drab, grey landscape. She says: ‘Colour tends to make people feel joyful and a lot of my work is about trying to imbue the grey realities of life with joy and hope.’ The artwork is titled Here We Come, Here We Rise, and comprises four undulating bands and triangular lenticular panels, which are arranged to maximise the kaleidoscopic effect as viewers move around the structure. Influences include Eadweard Muybridge’s motion studies as well as roadside structures from billboards to funfairs that build animation in the landscape via skeletal frames and a brightly hued skin.

The electricity station is part of Related Argent and Barnet Council’s ambition to be a net-zero carbon development by 2030 by investing in efficient infrastructure. It was built with primarily circular economy principles, with 50% of the structural steel salvaged from unused oil pipelines, reducing carbon emissions by over 40%.

Client Barnet Council and Related Argent

Design team Lakewna and If-Do Architects

Awards Civic Trust Award FX Public Realm Award

Completion 2023

CASE STUDY

DULWICH PICTURE GALLERY PLAYABLE SCULPTURE

The elegance and greenery surrounding the Dulwich Picture Gallery (DPG – completed in 1817, designed by Sir John Soane 1817, with a 1999 extension by Rick Mather), will soon be enhanced with an interactive sculpture, A Gift of Flowers, inviting visitors to break the ‘do not touch’ taboos of the typical cultural institute with its swooping and colourful form and multiple slides. Inspired by a bloom from Jan van Huysum’s Vase With Flowers, featured in DPG’s priceless collection, this bloom comprises petal-like forms made from reclaimed steel, sprayed in vibrant, weather-proof tones.

The sculpture is the result of recent and ongoing collaboration between the London Festival of Architecture (LFA) and the DPG, which has seen two temporary pavilions planted in the garden. The winning, interactive sculpture, emerging from an open competition, is by McCloy +Muchemwa with HoLD Collective and Cake Industries.

The design team has worked closely with local communities and groups to translate the sculpture into a dynamic element within the gardens. It will reinvigorate a currently under-used part of our grounds,’ says Chantelle Culshaw, DPG’s deputy director, ‘encouraging sensory-led, playful interactions from people of all ages. The team have placed access at the forefront of their design… which will allow families to enjoy the sculpture for years to come.’