It’s a living thing

THERE ARE certain more arcane areas of lighting, particularly alternative future sources, that merit revisiting once in a while to see how things are going. One area used to be OLEDs, for instance, but after flirting with its potential as an ambient lighting source that’s rather found its own niche in screen technology. Another is bioluminescence, especially as a potential source for urban lighting.

It pops up on to the radar every now and then because someone has done something with it – perhaps attracted media attention with talk of glowing mushrooms, or persuaded a town council to have an experimental scheme (Rambouillet – more on that later) or held small exhibitions and events to show the possibilities and aspirations (Daan Roosegaarde’s Glowing Nature programme, FX March/April 24). But then things go quiet again.

The impression is that there is perennially some general investigation going on in this area but we haven’t reached a point where it is a viable and realisable large-scale proposition. Which is a shame because it would have a lot of benefits: there are environmental advantages because, deriving from natural organisms, bioluminescent light sources don’t need electrical power, thereby reducing energy consumption and carbon emissions. They would also minimise light pollution, as they create only a naturally soft and diffuse glow. The sources are also self-replenishing, under the right conditions, offering a continual cycle of illumination without depleting resources.

But these are living organisms, which poses a number of challenges, not least ethical. They need to be kept in optimum conditions: luminescent algae, for example, need the right temperature, nutrient balance and oxygen levels. As well as being complicated, that can itself involve intensive use of resources.

Another issue is that light output not only has to be consistent and long-lasting but bright enough for certain purposes. In other words, what is an advantage where light pollution is concerned could be a problem for particular applications.

It is therefore perhaps inevitable that a lot of aspiring ventures bite the dust. One of the more hopeful ones in recent years was French company Glowee, which worked with the small town of Rambouillet, around 50km south-west of Paris. Rambouillet city hall signed a partnership with Glowee, investing £83,300 to turn the town into ‘a full-scale bioluminescence laboratory’.

ERDF, a largely state-run company that manages France’s electricity grid, was also among Glowee’s backers, the European Commission provided £1.4m funding, and France’s National Institute of Health and Medical Research (Inserm) also gave technical support.

The first installation, a series of cylindrical tubes containing bioluminescent bacteria, soothed post-jab patients in a Covid-19 vaccination centre with their soft blue glow. The source in this case was a marine bacterium called Aliivibrio fischeri, housed in tubes of saltwater, creating a luminous aquarium. There were plans for further exterior installations and signage applications, some of which materialised. Sadly, Glowee was declared bankrupt in 2023.

Inevitably, as the following items demonstrate, when the subject does occasionally rear its head it tends to be a kickstarter project, or part of a research study, or a novelty use designed to grab publicity. Whatever the reason, it is confirmation that people have by no means given up on the idea.

Bioluminescence is light produced by a chemical reaction within a living organism. It is a type of chemiluminescence, or the chemical reaction where light is produced. (Bioluminescence is chemiluminescence that takes place inside a living organism.)

Most bioluminescent organisms are found in the ocean and include fish, bacteria and jellyfish. Some bioluminescent organisms, including fireflies and fungi, are found on land. There are almost no bioluminescent organisms native to freshwater habitats

The chemical reaction that results in bioluminescence needs two unique chemicals: luciferin and either luciferase or photoprotein. Luciferin is the compound that actually produces light. The bioluminescent colour (yellow in fireflies, greenish in lanternfish) is a result of the arrangement of luciferin molecules.

Some bioluminescent organisms, such as dinoflagellates – a type of plankton – synthesise luciferin independently. These are the tiny marine organisms that can sometimes be seen sparkling on the surface of the sea.

Most bioluminescent reactions involve luciferin and luciferase, but some involve a chemical called a photoprotein. Photoproteins combine with luciferins and oxygen, but need another agent, often an ion of the element calcium, to produce light.

Photoproteins were only recently identified, and scientists are still studying their unusual chemical properties. Photoproteins were first studied in bioluminescent crystal jellyfish, Aequorea victoria, found off the west coast of North America.

Source: National Geographic (Education)

BIOLUMINESCENT FLOWER PARLOUR

BOMPASS AND PARR/AGLAÉ

Bioluminescence is right up Bompass and Parr’s street. The multisensory experience design studio likes ‘to deliver emotionally compelling experiences to a wide variety of audiences’.

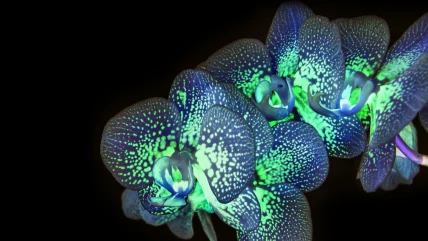

Held last autumn in Canary Wharf, the Bioluminescent Flower Parlour was a pop-up affair featuring glow-in-the-dark flowers. The floral displays absorb a ‘fluorescent’, nutritive serum (presumably when they are watered) developed by the glowing plant concept company Aglaé. The luminescent effect is enhanced by UV lighting. The company is coy about exact details, though its name would perhaps indicate the use of algae. However, the use of UV suggests fluorescent or possibly phosphorescent rather than bioluminescent techniques. However it is achieved, according to the company it involves no genetic modification and is not harmful to the environment.

The idea was spawned when founder Sophie Hombert wrote a thesis on the domestication of plants and subsequently partnered with research laboratories to develop the serum. The company’s two main activities are events and research.

Aglaé offers cut flowers (for transient events as the effect lasts as long as the flowers), green plants with roots and, actually with real potential for interiors, stabilised (‘mummified’) plants, which apparently have a lifetime of three to five years. These can be used for plant walls, planters, reception furniture or even green ceilings. Aglaé has a prestigious portfolio with Disney, Dom Perignon and Chanel among its clients.

It may be on a different path but it is on the same page as the likes of Roosegaard (mentioned on the previous page). It says its ‘long-term goal is to design soft, living, electricity-free lighting solutions. Together, let’s imagine a more sustainable future where our parks and gardens will be lit by the glow of trees.’ www.design-aglae.com

LUCID LIFE

CHRIS BELLAMY

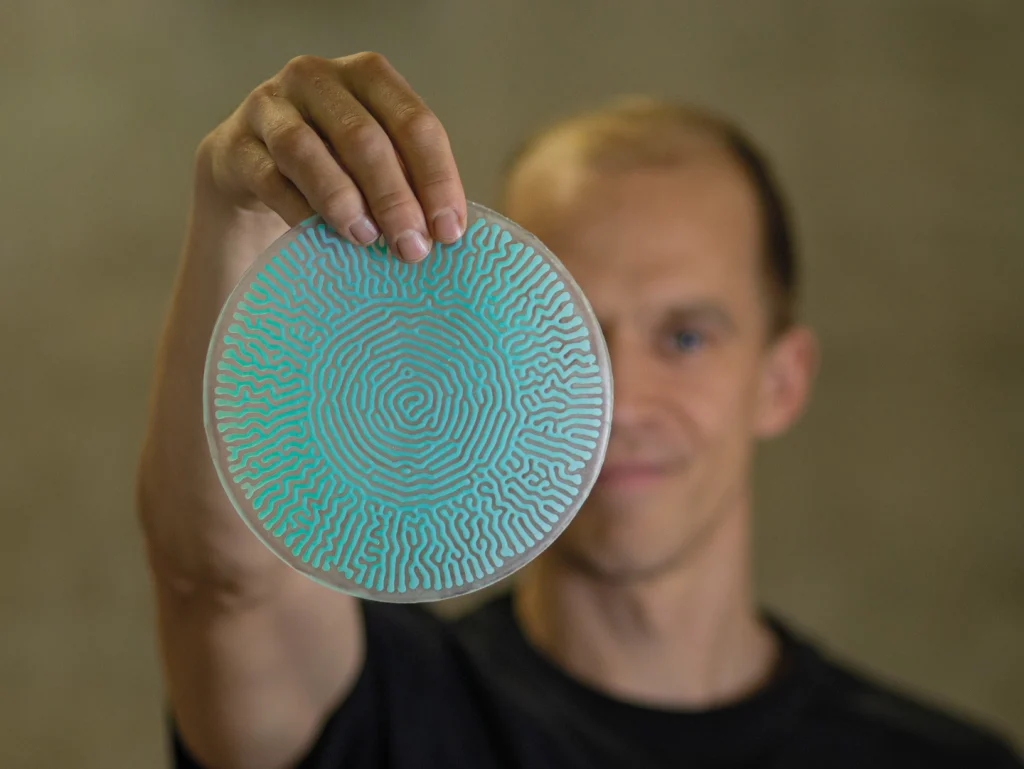

Chris Bellamy is a biodesigner and engineer who studied engineering at the University of Cambridge. Starting at Jaguar Land Rover (helping to develop its first electric vehicle, the Jaguar I-Pace), he then moved to developing customisable and recyclable shoes. His research now is focused on how living materials can be used in our everyday lives, ‘co-evolving traditional knowledge with the latest scientific research’.

After a bio-prospecting trip to French Polynesia in search of novel microorganisms, Bellamy was inspired by the indigenous community’s connection to nature, and wanted to see how design could bring these two worlds together. The result was Lucid Life, or ‘Marama Ora’ in Tahitian, based on a living material that emits light in response to touch.

Developed with the support of the Francis Crick Institute for biomedical discovery, the material uses bioluminescent algae, like those that live symbiotically with corals. The microorganisms are encapsulated in a way that enables them to live, sequester carbon, and emit light for more than six months. They need only sunlight in return.

In collaboration with three different Polynesian artisans, Bellamy co-created a series of artefacts using the bioluminescent material: a drum, a swimsuit and a necklace, ‘which demonstrate how living materials can reconnect us to nature, and how biotechnology can move beyond the laboratory’. www.chris@biocrafted.com