HOW TIMES change. Only in 2018 the United Nations was confidently predicting that the world’s major urban centres would be boosted from 55% of the global population to 68% by 2050. Those figures should be under revision as I write, because the fallout from the Covid- 19 pandemic includes a serious shift away from the big metropolises and out to the leafier, more affordable regions.

In October 2022, Creativeboom.com ran a piece called ‘Why artists and designers are moving out of big cities’, citing this drift to the country as ‘one of the biggest stories of the pandemic’. They found a multitude of graphic designers, illustrators, photographers and artists choosing rural over urban – many of them returning to the small towns or villages where they grew up. In doing so, they brought valuable incomes to spend locally, which in turn drove demand for new culture and leisure spaces and hubs. For architects and interior designers, enlightened and ambitious clients started populating these rural idylls.

Go west

Architects Oliver Bindloss and George Dawes were working for Jamie Fobert in London on various prestige cultural projects, but left for the rolling greenery of Somerset in 2018 and have never regretted it. Says Bindloss: ‘Twenty years ago when I started in the profession you couldn’t be a rural architect. If you wanted to be a good architect and get interesting work you had to be in Manchester or London, or you could get away with being in Bath. There are now quite a few architects who are rural-based.’

Luckily for them, there seems to be plenty of residential work for youngish, newly relocated professionals interested in adapting their homes to contemporary standards. Bindloss Dawes’ website boasts a slew of sophisticated extensions and refurbs. Says Bindloss: ‘People are leaving London younger and they want more modern houses. They also want that cultural offer they were used to… There’s a lot of interesting movement happening in the country, whether it’s rebuilding or cultural infrastructure.’

Bruton, where the pair has set up their joint practice, was already a magnet for cultural tourism, since global gallery brand Hauser & Wirth launched its first rustic outpost on the edge of town in 2014. The gallery is now a pivotal presence in the town’s year-round activities and attractions, with a programme of international art exhibitions, plus an acclaimed restaurant now joined by a farm shop. Hauser & Wirth recently added a craft space on Bruton’s high street, now populated by cafés, artisan delicatessens and boutique hotels that have sprung up in the past decade to cater for well-heeled visitors (including second-homers) as well as the wave of fugitives from the capital.

Another lure in the region is The Newt – a luxury hospitality development from South African business magnate Koos Bekker and his partner Karen Roos, a former editor-inchief of Elle Decoration South Africa. They have restored and refurbished the Grade II-listed Georgian pile of Hadspen House, launching it in 2020 as a boutique hotel and spa, with farm shop, restaurant, cider press (using apples from their own orchards), and horticultural museum set within stunning formal gardens designed by Patrice Taravella. Having successfully launched and run something similar in South Africa, with Babylonstoren – where high-end hospitality built around vineyards has been the norm for decades – the Newt is run as a kind of country club, with an annual membership enticing people to use the grounds and restaurants year-round.

Though Bindloss Dawes arrived too late to benefit from patronage by The Newt, their practice has certainly been boosted by evolving cultural investment. Most recently, they refurbished a Methodist chapel in Bruton for former London gallerist Jemma Hickman and former Hauser & Wirth Somerset director Alice Workman, who, in late 2022, set up as an independent gallery Bo Lee and Workman. eir ‑ rst exhibition was a solo show for Jonathan Michael Ray. Ray told me at the opening he’d relocated from London to Cornwall prior to the pandemic, and relishes the new freedom from ever-rising rents (he also has a young family) and the supportive arts scene he has found there.

Ray’s news of an expanding cultural community in Cornwall was substantiated on a recent two-day visit to the Eden Project. It became clear from conversations with almost everyone encountered – in cars, bars or restaurants – that a more vibrant Cornish arts scene has been generated through a new critical mass of spaces and producers, one of them being the Eden Project itself. That iconic cluster of geodesic domes by Grimshaw Architects has become such a recognisable landmark for the region, but it is also animated by a renewed mission not just to use the horticultural and botanical living laboratory of the domes to foster the necessary sense of wonder and appreciation of our planet’s amazing biodiversity, but to curate a cultural programme that foregrounds artists who are enriching our understanding of the environmental crisis unfolding around us.

The Eden Project’s mission includes expansion across the UK, taking Eden Project-style experiences to other former industrial sites, thereby driving regeneration in those regions. For example, Eden Project Morecambe has received £50m of the UK government’s Levelling Up funding and is envisaged as a major new attraction – ‘a seaside resort for the 21st century’, with Grimshaw Architects providing more of those iconic biodome pavilions filled with plants, spaces for live music, performance, learning and engagement.

Dundee is also earmarked for Eden Project investment, with a bold scheme by Feilden Clegg Bradley having been granted planning permission. As the Eden Project’s senior arts curator Misha Curson tells me: ‘Our proposed sites are a mix of post-industrial sites that are now being reclaimed to become more biodiverse and wild sites, working in partnership with local conservation and economic opportunities. We have a matrix around how we engage. We ask: what’s possible? Where is there a need? Where can we make a difference? It also has to relate to our global mission – how does it respond to the planetary emergency?’

Within Cornwall, Curson cites a host of recently launched and booming spaces for art and creativity. CAST (which stands for Cornubian Arts and Science Trust) is foremost among them. Set in the struggling market town of Helston within a simply refurbished Victorian school, it offers artist studios, a fully equipped ceramic workshop, a meeting/ events space and café.

Founded by Teresa Gleadowe as an education charity, it runs Art Lab sessions for primary schools, free holiday workshops, and a Saturday club for youngsters aged 12 to 16. CAST was one of the first organisations to win substantial funding from the Arts Council England’s Ambition for Excellence scheme (underpinned by £35.2m funding from the National Lottery), aimed at supporting a more ambitious arts infrastructure outside of London. Gleadowe clearly understands that the stronger the collaborative spirit, the richer the ecosystem. Thus, in delivering a three-year project with international artists, it partnered with local arts organisations including Kestle Barton, Newlyn Art Gallery & The Exchange, and Tate St Ives.

The Eden Project’s Curson says that when cultural initiatives are most effective as economic triggers it’s where there is an existing ecosystem that new projects can tap into. She cites many longstanding small organisations in Cornwall, such as the Miners and Mechanics Institute – a community centre that programmes music, film and screenings – as one of the longeststanding, as well as art schools in Plymouth and Falmouth. She says: ‘There’s a will to create culture and participate in culture here. Through these spaces being available there’s an opportunity for everyone to live a rich and meaningful life, enjoying living costs that are generally cheaper than in the big cities.’

Sussex Modern

Sometimes it takes a crisis – economic or otherwise – to reveal the existing networks of sympathetic businesses and generate among them a desire to work together rather than compete. Such seems to be the case in another picturesque region of the UK. Sussex is a county with rolling countryside, vineyards, historic houses, charming villages and so much more than the coast, to which most tourists from the capital or further afield usually direct their attentions. Sussex Modern is a new initiative to draw tourism through and across the region, harnessing the attractions of both counties – East and West Sussex – under the banner ‘art, landscape, wine’.

Yes, wine. Sussex vineyards, it seems, are benefitting from global warming. The layer of flint over chalk that typifies its geology, giving an optimal mixture of good drainage with moisture retention, is very similar to that of France’s Champagne region (which is now struggling to produce traditional yields against increasing episodes of drought and higher temperatures). While most vineyards concentrate on sparkling wine, there’s a chilling moment in the ‘tasting’ experience of our Sussex Modern press tour when we’re told: ‘Soon, we expect to be able to produce still and even red wines.’ Hmmm. Is this a ‘silver lining’? Not for everyone. However, the Wiston Estate is already producing a very decent rosé.

Many of these English vineyards have taken a leaf out of the world’s major wine-producing regions (including the aforementioned South African estates) and seized the opportunity to throw hospitality into the mix. Tinwood and Ashling Park have added small but cosy cabins in among the vines, just a short (and possibly tipsy) stroll from their new restaurants, which are set up for romantic and social dining as well as corporate events – if some are a little too corporate for my tastes. The older and more established Wiston Estate has recently completed a £6m refurbishment through ECE Architecture (with offices in Sussex, Bristol and London) to create substantial wine storage and tasting facilities plus elegant dining spaces indoors and out, repurposing farm buildings in a way that really celebrates the regional materials and typologies.

But vineyards are only a part of what’s on the menu for Sussex Modern. As any visitors will see there is a spectrum of nearly 50 options now beautifully laid out in a pull-out poster and map that can be picked up at any of the designated venues. Cultural attractions include Charleston, the former farmhouse home of artists Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, which has a year-round programme of exhibitions – recently adorned with a Jamie Fobert-designed restaurant and event space, and even more recently joined by a new exhibition space in nearby Lewes. There’s Glyndebourne Opera House, Chichester Theatre (which has a long-standing reputation for debuting exciting new shows before they head to London’s West End), and the highly regarded Pallant House gallery in Chichester.

Nathaniel Hepburn, current director of Charleston – formerly of another Sussex attraction, Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft – has been instrumental in driving the Sussex Modern initiative. Growing out of a £15,000 ACE grant in 2016, Hepburn claims the scheme’s collaborative approach has subsequently generated £1m from the visitor economy.

An enthusiastic participant in the initiative is Nicola Jones, who is seemingly single-handedly reviving the quaint village of Petworth, previously known for its antiques market and the National Trust property Petworth House – arguably offering the finest art collection of any of the NT’s venues.

Her pride and joy is Newlands House Gallery, a Georgian townhouse, which she refurbished tastefully in 2022; majoring in contemporary and 20th-century photography, the pale walls and timber floors formed an elegant backdrop to the Eve Arnold show she put on in summer 2023. But she has also brought high-quality delicatessen retailing to the town, and snapped up a variety of ailing pubs and cottages, putting her own boutique B&B/ gastropub stamp on their interiors and the food offering.

Again, it’s the critical mass of attractions that Jones hopes will draw cultural tourists to the area, building on existing assets such as the Towner Gallery Eastbourne (which hosted the Turner prize exhibition 2023-4), Bexhill’s De La Warr pavilion, and the glorious eccentricity of West Dean College of Arts and Conservation and, of course, the charms of Brighton.

This percolation of high-spending, art loving tourists, as well as artists, away from the cities is far from a UK phenomenon. Wherever creatives have discovered abandoned but still functioning industrial buildings, and had the wherewithal to convert them, new cultural destinations have sprung up, from Provence – where I have visited and written up for FX the hospitality and cultural offer now available to visitors – to Arles, a former railway depot now replete with a Frank Gehry-designed crinkly cultural landmark. As for Berlin, in spring 2023, I visited the former early 20th-century power station E-Werk Luckenwalde south of Berlin, rescued from dereliction by artist Pablo Wendel, and now run together with his partner, curator Helen Turner. Its turbine hall is every bit as atmospheric as London’s Tate Modern, and it now hosts regular exhibitions and festivals around the arts, while the gently decaying interiors of its adjacent 1920s municipal swimming pool, the Bauhaus Stadtbad, can host anything from community theatre to opera – as it recently did with a triumphant re-stageing of the Venice Art Biennale’ Golden Lion-winning climate opera, Sun, Sea and Sky.

Finnish flair

With their deep love of nature and culture, it’s not surprising that Finland has been ahead of the curve here in reframing the rustic locations of former industrial sites to appeal to today’s history and culture-loving travellers. Over the past 20 years, one of Finland’s most significant 19th-century ironworks in the village of Fiskars, an hour’s drive south west of Helsinki, has slowly transformed into a thriving hub for artists, makers and cultural tourism.

Fiskars, set deep within a forest and with a river rushing through it, was the perfect location for an iron foundry, with local timber used to stoke the fires and the rushing water used initially for cooling and then hydro powering the machinery. It celebrated 365 years as a foundry in 2024. But having been taken over entirely by the famous Finnish company Fiskars, creators of the country’s iconic, orange-handled scissor brand (and now owner of many other iconic Finnish design companies), when work was relocated to more modern production facilities a few hundred kilometres away during the 1990s, the company didn’t want to see the handsome stone and timber workspaces nor the cute timber workers cottages go to waste, and invited writers and artists to move in. The vibe is extremely collaborative – blacksmiths, glassblowers, woodworkers and artists work together on many projects, taking advantage of the generous studio spaces. The artists have their own co-operative and through this they run their own gallery and shop facilities. The whole site now attracts a few hundred thousand cultural tourists a year, many of them spending a day or more, enjoying the Fiskars-owned and run hotels and restaurants. Says Elisabeth Blomqvist, sales and marketing manager for Fiskars Village: ‘I don’t think anyone would have thought of this happening in the 1990s. It makes sense because the Fiskars brand was born here. The orange scissors were designed here. So crafts-minded people are drawn here. It’s a continuation of craft traditions.’ There are now around 600 people living in Fiskars. Says Blomqvist: ‘We have lots of people who live here but work in Helsinki and they go there once a week. Fiskars sells plots for building your own home. We are trying to get more people to move here. There’s a small school here. To keep that school active and to keep it open we need people to move here with their families. Working in the village and working remotely is very do-able. The train goes from (nearby) Kaaria to Helsinki and to Turku.’

There has also been recent investment elsewhere in the region to amuse and sustain aesthetically oriented travellers. The Baro hotel opened in 2021 – an exquisite collection of subtle but sophisticated timber-clad cabins perched high in a forest along the coast. The scheme was the brainchild of developers, interior designers and entrepreneurs Netta and Jussi Paavoseppa (working with architect Lena Weckstrom of Helsinki-based Macao Design). The Paavoseppa duo was then invited by Fiskars village to bring their trademark dark palette, soft lighting and luxurious materials vibe here, refurbishing the Torby hotel in 2023, set in a 19th-century building where fine cutlery and chandeliers used to be made.

In the nearby coastal village of Ekenas, Alvar Aalto’s delightful Villa Skeppet – one of his last private houses, designed for his great friend, the Finnish travel writer Göran Schildt and his wife Christine – has just been fully refurbished and reinstated as the lightfilled home the writer and his wife enjoyed, including paintings on the wall by Aalto.

Also, the town’s local art gallery and museum Chappe Art House has been expanded with a striking new wing, by Helsinki-based JKMM Architects, which transformed the capital’s Amos Rex Gallery in 2018.

A few minutes’ drive away from Fiskars and Ekenas, there’s a quality of almost found space to the former iron foundry stronghold of Billnas. With around 20 buildings scattered alongside a river, grass grows long on the verges, cobbled paths meander from one industrial building to another, several of the structures are still shrouded in decades of disuse. But all have a scale and grandeur appropriate to this having been an iron production powerhouse for over 300 years. At its height there were 1,000 employees working here. But all seems sleepy and easeful now; I even spotted two donkeys being taken for a walk on my visit in September 2023. But for Finnish events management guru Olli Muurainen, the slow regeneration of this site as a place for conferences, festivals and executive retreats, has become his legacy project.

The city of Rasebourg bought the site off the Fiskars company – which had acquired it in the mid 20th century but sold it in the 1980s – and they spent over a decade looking for a buyer who could revitalise the buildings while preserving their history. They approached Muurainen in 2008, as a celebrated Finnish entrepreneur (albeit living in Singapore). He says: ‘There was sleet everywhere. Garbage everywhere. Trees and bushes nobody had taken care of for over 20 years. But I could see that it was a beautiful spot.

‘The oldest elements are foundations of the bridge from 1690. There are 15 buildings from the 1770s. Most of the buildings are from 1800s. We have a few that are 19th century. This place has seen all the industrial stages: basic iron, tools, furniture, and then been abandoned for 30 years. I thought I could make it transition to the service economy. I made my decision with my heart not my brain.’

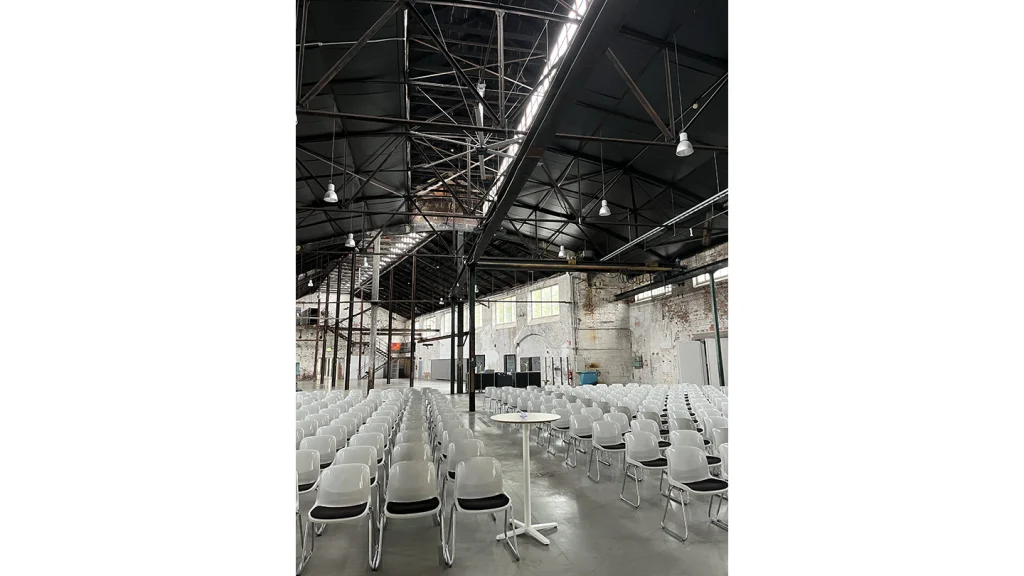

Though Muurainen declares that he’s ‘very sensitive to aesthetics – I don’t need an architect to do visualisations for me, I can just close my eyes and just see it’, he worked with restoration specialists Rakennusliike Heinämaa to help restore and refurbish seven of the buildings, at a cost of €10m. There are seven more to go. The emphasis has been on stripping back to reveal the bones of these buildings and make minimal additions – luckily, the buildings have very good bones. There are currently two hotels, a restaurant, a museum (of woodwork, in one of the two surviving furniture factories) and several event spaces, including the most spectacular: a triple-height blast furnace hall that, with light pouring in from its raised, ventilated roof structure, feels almost like a cathedral. A 1930s former minimarket that used to serve the workers has been converted into a kind of executive den, with conference suite, screening room and sauna.

Still in its early days, the main customer group is Swedes – ‘there is nothing like this in Sweden’, says Muurainen. The business is ‘anything from small management teams for 20-30 people, then weddings, and stand -up comedy on Saturdays. We had 300 people last Saturday (at a comedy gig). We had a rock concert last week too. Then employee parties. There’s a very wide range of events. This place is quite unique.’

Though the place is shut for the winter (Finnish winters being too harsh to tempt out even the most hardened, nature-loving executives), Muurainen has built that seasonality into his business model, and enjoys 70% occupancy rates from spring to autumn. He seems in it for the long haul. ‘It’s a very expensive hobby for me but it gives me a purpose. It’s symbolic, bringing a community back to life.

‘We are more than halfway through the project. So maybe in seven years’ time it will look as I envisaged.’