WHAT OBSTACLES do women face in becoming leaders in the design world? That’s a fascinating question to pose as we hit the quarter mark of the 21st century.

Progress is evident, but in many sectors, in far too many parts of the world, women are still struggling to throw off centuries of chauvinism – or worse. In the early 20th century, we saw female designers of textiles, furniture, interiors, shine brightly – Annie Albers, Charlotte Perriand, Sonia Delaunay – only to be subsequently sidelined, their contribution often appropriated by the men who harnessed their talents, or overlooked by the (usually male) experts writing the monographs. Thankfully, these women are being rediscovered and celebrated in their own right.

For women architects, there is still much ground to be gained. Despite a roughly equal intake of male and female architecture students over the past few decades, in 2021, according to the Architects Registration Board, the number of women registered as professionals was still only 29.6%. Challenges are systemic, due to a raft of issues, including working practices often hostile to family life. But until Zaha Hadid broke through that tough, triple-glazed ceiling, the profession itself seemed unable to entertain the idea of a great female architect. This attitude was in evidence as recently as 2014 when the BBC airbrushed Patty Hopkins, practice co-director and co-founder with husband Michael, of Hopkins Architects, out of a promotional portrait for their 2014 documentary series The Brits Who Built the Modern World so that only the males remained (Rogers, Farrell, Foster, Hopkins and Grimshaw).

The past five years have seen shifts in the right direction, due to campaigns, such as that run by gender parity action group Part W flagging up the industry’s appalling record of overlooking women for awards and recognition, and Architects Journal’s annual survey, which exposes the lack of parity in pay.

While the atmosphere may now be more receptive to female talent, those years in obscurity were not wasted: women developed skills as collaborators, facilitators and observers, which are still informing and enriching their practice. Thinking holistically, working co-creatively and across disciplines, an ability to fuse aspirational aesthetics with pragmatics and an understanding of people: these are skills in which women in design have excelled. By recognising these qualities’ importance to the industry as a whole, they become part of a more enlightened design practice, whatever the designer’s gender.

There are now a handful of women architects with their names on the company masthead, though most have succeeded by competing with men on their own terms – prioritising putting a distinctive visual stamp across all projects, and continuing to reify the building as object. Marina Tabassum, profiled here, is a rare exception of a female-led and self-named practice, but she prioritises planet, people and locality in every case. Sometimes being, effectively, an ‘outsider’ in your own profession – and choosing to remain so – allows you to see how things can be done not just differently, but better.

Katy Marks

Katy Marks studied both Architecture and Environmental Design, at Glasgow School of Art, Madrid and Cambridge University. She soon demonstrated an entrepreneurial streak, setting up a network of not-for-profit, co-working spaces, Impact Hub, in 2003, with fellow students, using their student loans as start-up funding. It has since become a major player in the co-working universe. Marks handed on her directorship in 2005 when she joined architects Haworth Tomkins. Seven years later, she left them to set up Citizens Design Bureau (CDB) but continued as an external consultant to complete Haworth Tomkins’ Liverpool Everyman project, which won the 2014 Stirling Prize.

Parenthood, as for so many women architects, proved the sticking point. She says: ‘I worked for an office I really loved and who valued me and were very kind and supportive. But it was run by men, and at that time they were very clear that you can’t run a project part-time. I understood why they said that, I just thought I can do it my own way… I also thought, as a director, you’re overseeing lots of projects; you’re never working on one thing full-time. So why can’t I just delegate, or just work on fewer things so I can do it in a flexible way? I’ve also worked incredibly hard, and I work late often, which is not very healthy.

‘So many women architects end up setting up by themselves, doing private work, doing consultancy work. Covid has changed that massively. Many more offices are more open to being flexible. That’s been good for women and men.’

Does her gender have a bearing on the environments she’s thrived in? She says: ‘I don’t think it’s a surprise that we’ve made a name for ourselves in the arts sector, the cultural sector: it’s a sector largely run by women. I’ve been fortunate to work for clients who don’t think: “Can she really do it?” Their attitude is: “You made it and we respect you. We know what graft you put in.” But when you go into a corporate environment, such as working with developers, it’s very different and much harder as a woman – it’s harder to get into those conversations in the first place because I’m not hanging out at golf clubs. I never go for networking drinks.’

During the Covid pandemic, the culture sector took a massive hit, but CDB diversified into social housing. ‘We need to find ways of being nimble. We’ve managed to really jump sectors and show that our process can be applied in lots of different ways. We bring value by seeing things in a particular way, by reinterpreting briefs, by seeing sustainability and viability as part of the same coin – often they’re pitched against each other. I’m genuinely interested in the business model of the clients we work with. We work with a lot of community clients, small charities, who are often living hand to mouth, relying on subsidies and grants. One of the reasons why we get asked back is that we’re really attuned to their commercial reality and so the process we run is not just a design process – it’s almost a business-planning process as well, to see how we can get the biggest bang for their buck… and really help with their financial stability… because if it’s not financially viable it won’t happen.’

Recently, her problem-solving streak led Marks down an unusual pathway: into lingerie and swimwear design. Following a mastectomy for breast cancer treatment, she found herself repelled by the usual postsurgery bras that prioritised prosthetics. She wanted to own her asymmetry. Having found the necessary collaborators and funding, Unobra launched in 2023 and has had enthusiastic coverage everywhere from the BBC to The Times and The Guardian.

How does she find the energy for this as well as running a practice and raising two sons? First, she credits her husband for his unstinting support. She says: ‘I don’t have time. I do it on the side. And it’s really challenging, but having confronted your own mortality as I have, I have just become really committed… to saying “no” to the things I don’t want to do and that don’t give value to me or anyone else and making time for the things that do.’

Marks doesn’t see money as the main metric for success, but she is frustrated that big, corporate schemes are usually the most profitable: ‘There’s literally an inverse correlation between the social value that you create and the amount of money that you earn.’

She doesn’t waste time weighing up successes and failures: ‘I just see it as a constant process of refinement and learning… For me, if we can demonstrate that our process is humane and brings richness in the conversation, I think it transmits through what you get out at the end. And it’s always about having a bit of soul. I want people to go into a building we designed or put on our bras and really feel the best version of themselves. To make spaces that empower people to feel full of energy, to change minds: that to me is success. Getting awards or whatever is very nice, but the real success is when you feel that you’ve created something that people genuinely love.’

That ability to ‘identifying what it is that makes a place loved’ is vital in dealing with heritage buildings – ‘it means you can do things that are resolutely new, and not be afraid’. She cites Manchester’s Jewish Museum as a prime example. ‘The normal thing to do with an extension on a Grade II* listed building would be to put something recessive, hanging back. We’ve managed to do something quite bold, which really amplifies the existing building. I felt we needed to give it greater street presence without diminishing it. We made that argument with Historic England and they bought into it.’

With St Peter’s Church, in Epping Forest, CDB was up against tough competition, but won the client over by pointing out that the brief (a new extension) was impossible to achieve on the proposed budget – and, ultimately, not necessary. ‘We looked at the history of the church and saw that it had started life as a square chapel and been extended. We said let’s take it back to that square footprint, and in the rest of the space build community facilities. So that’s what we did… They loved the intimacy of it. It’s still very spacious. And it’s so atmospheric. It’s about squeezing every last bit of value out of the budget.’

Marina Tabassum

Marina Tabassum’s early childhood was marked by chaos and insecurity, thanks to Bangladesh’s War of Independence (1971). ‘I was introduced to death and destruction before I was enrolled in elementary school,’ she told an audience for her Sir John Soane Museum lecture in 2021. Growing up with no toys and little food, imagination came to her rescue: ‘I realised very early in life that limited means cannot limit dreams; these limits instead open the window of innovation.’

The family moved to live with her grandparents in Dhaka, to which they themselves had fled, post India and Pakistan’s partition in 1947. With a slum on the other side of their garden wall, she says she was aware of the privilege ‘we were born into’.

‘Unlike many, my family had the means to provide my siblings and me with a good education and opportunities for growth. I grew up in an environment where there was no discrimination between boy and girl. Even more fortunate, our parents instilled in us the importance and value of giving. My father being the only doctor in the neighbourhood, we would wake up each morning to a long line of patients from the neighbouring slum; he would attend to each one of them before setting off to work. In many ways, I seek to repeat that compassion through my architecture by expanding beyond the architectural programme, moving past the site boundary to attend to the human condition and the local ecology of sustenance.’

Her preoccupation with home, and the true meaning of home, she attributes to her own and her family’s history. ‘We, the third generation of an immigrant family, grew up with stories and mental constructs of a lost home that exists only in our imaginations. In Bengal, however, home, or “desh”, refers to one’s origin, the village home. Locating “desh” is a shared quest, embedded in the culture of Bengalis.’

In the delta around Dhaka, she found her ‘desh’.

‘There is inherent wisdom embedded in living symbiotically with nature,’ she said. ‘There, families do not aspire for their own dwellings to be different from their neighbours’; values are rooted in homogeneity and a communal way of life.’

A landmark building for her was encountered when studying architecture at Bangladesh University of Engineering: the parliament complex by Louis Kahn: ‘It was ritualistic for architecture students to visit the complex with our professors. The ambulatory is the urban street that connects eight building blocks to the central chamber: the street is a room lit by sunlight filtering through glass bricks embedded in the roof. The brightness of the direct sun filtering through the ceiling bricks reveals the dramatic play of light and shadow… How the atmosphere inside a building, in this building, could change with the movement of the sun and clouds was my first lesson in daylight.’

This reverence for ‘the magic and harnessed power of light’ has been translated into all her projects. Rejecting the growing consumerism and corporate architecture she saw in burgeoning Dhaka, she opted not to facilitate this new ‘generation of fast-bred buildings, primarily focused on profitability’. She told the Soane audience: ‘The icon-mania of the superrich and stardom of architects brought about a crisis. It is a point of crisis when an architect must decide whether to indulge in easy excitement or to choose a path of resistance. I chose to resist, to deny temptation and to search within; within the land I grew up in, the place and country I call home.’

Forming Urbana, with her then partner Kashef Chowdhury, in 1995, they turned down commercial but soulless projects to pursue more rewarding work. That included lowbudget but beautiful residential dwellings that ‘respond to the tropical climate with large openings, terraces, verandas and open green space’. One and a half years after setting up, they landed the prestigious commission to design the Museum of Independence of Bangladesh in Dhaka, completed in 2013.

She set up Marina Tabassum Architects (MTA) in 2005, with the intention of making the most of local materials, geometries and apertures to optimise internal climate and connection with landscape. Her grandmother donated some land and commissioned her to build a mosque. It became a passion project, funded and built by local communities. Bait ur Rouf Mosque broke ground in December 2006. It really put MTA on the map, and netted her an Aga Khan Award for Architecture. She wanted to ‘search for the essence of Islam, devoid of ritualistic and symbolic attributes’. Reaching back to the original purpose of mosques as places of community, as well as communion, she says: ‘The main prayer hall is designed as a place of refuge where everyone is welcomed; a pavilion on eight columns wrapped in a brick structure that houses the ancillary functions of the mosque. The punctuated brick walls and open courts help to keep the building ventilated throughout the summer… and create a truly porous building, open to external light, sound and climate.’

MTA has dedicated huge time and energy in devising temporary but robust structures for refugees and those navigating hazardous climatic conditions. For workers dealing with frequent flooding in the Panigram Resort, Jessore, MTA devised simple modular, demountable homes, built on stilts, to deal with frequent relocations caused by fluctuating tides. A flatpack scheme, the Khudi Bari, was devised during the Covid pandemic in 2020: a lightweight modular structure of 3.0m2, made of bamboo with steel joints, easy to assemble and disassemble. It costs £300 and can house a family of four. Hundreds of families have been housed in these structures already.

In summer 2025, her unique sensibility will land in the UK, with the construction of the Serpentine Pavilion. A Capsule In Time is an elongated capsule-like structure of four, wooden forms, with an open, central court. It draws on the South Asian architectural tradition of Shamiyana tents or awnings, used for gatherings. Part of the pavilion is kinetic and can close to create a larger gathering space. All the materials, such as wood for the structure with built-in shelving options and the translucent façade, have been sourced locally and designed with the pavilion’s afterlife in mind – which is envisioned as a library.

Tabassum concludes: ‘It is immensely liberating to realise that an architect is not bound by the four walls of a building… One can transcend visual dominance and objectmaking towards an architecture of relevance, in response to time’s needs.’

Hanna Harris

Hanna Harris, chief design officer for Helsinki, is one of very few design bosses appointed to only a handful of the world’s modern cities – Seoul, LA and Eindhoven being the others. The role emerged when Helsinki was a World Design Capital in 2012, and Harris is only the second person to have taken on that title.

The job, in essence, is ‘to create an environment where people can thrive’. But what that means covers an absolute multitude of departments and issues, from education and the city’s climate-neutral ambitions (targeted for 2030) through to activation of public space, parks and playgrounds.

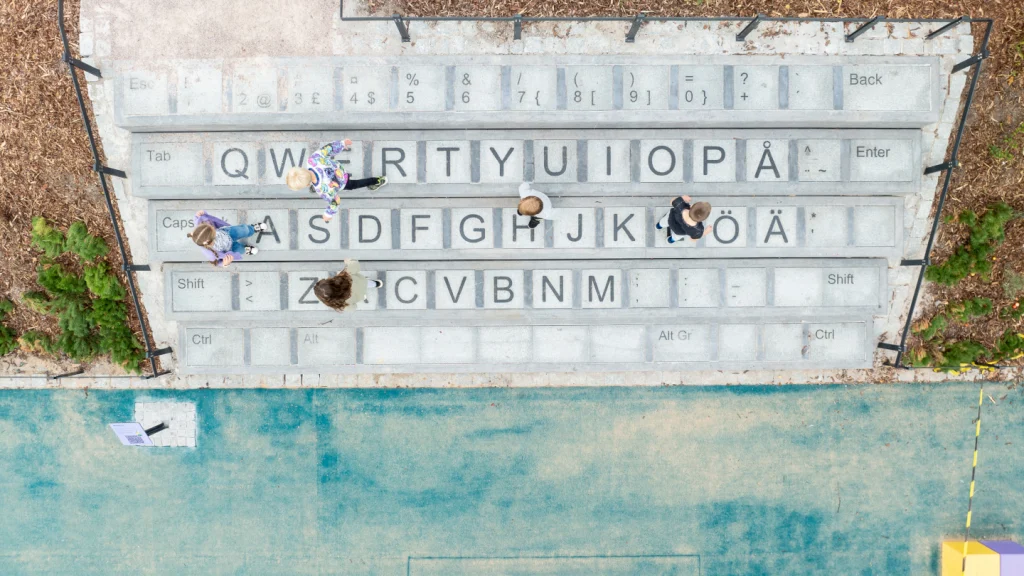

Five years into the job, one of her proudest achievements is helping to conceive and then deliver a brand new kind of playground: one that helps to educate children on how computers work. The Somatic Playground in Ruoholahti was co-created with children’s author Linda Liukas, whose books help children find the fun in technology. Working together with Landscape Architecture agency Näkymä Oy and play equipment specialists Monstrum, the playground has been a huge success. But making it happen involved opening up dialogue with people who might not normally be consulted, and getting cross-disciplinary conversations going – a core component of her job. Says Harris: ‘I’m trying in my work to change how we do things but also putting in place certain structures, building bridges in places that give us an opportunity to look at things differently. The playground has been one of those things. I don’t get involved in every single playground in Helsinki but this one I did, because it’s been a bit of a change agent.

‘We started by pairing Linda with landscape architects to think what this could mean in terms of a park. Then we talked to the education people, and our chief of children’s culture. When everyone was enthusiastic, we managed to get it into the ten-year investment plan (it cost around $1.6m).’ Now a booklet of games and exercises that are built into each play space have been shared with all of Helsinki’s schools, so that the park becomes part of their digital literacy programme.

Helsinki’s child-inclusive attitude was recognised in autumn 2024 with a UNICEF Child Friendly City award. Says Harris, proudly: ‘It’s the first Nordic city to receive that award.’ The tribute was not just for the city’s excellent playgrounds (110 in a city of around 660,000 people), but, according to Harris, for ‘our thinking around how we can work even better with children and young people: how can we help them to understand and read the urban environment? What capacity do they have to take part in it, and take ownership of their neighbourhoods?’

Design and computer literacy is stitched into the national curriculum: Finland was one of the first countries to teach digital literacy at primary school (not just how we use computers, but why, including that vital element of safeguarding), as well as design and architecture, which was introduced into the school curriculum in 2017. Harris says: ‘I really believe that design and architecture are crucial parts of our everyday lives, and if we can give children the tools for understanding how that works it will help them understand this world and become active citizens in it.’

Agency is a strong aspect of what Harris is trying to achieve, but that only comes through building understanding – not just with your citizens, but with the public sector employees who look after them: ‘Cities are messy things. Governance is complicated. Administrative silos are so hierarchical, there will always be different departmental ways of doing things, different budgets prioritised. My chance to chip in is essential in design, in bringing those voices together.’

While answerable to the chief executive of the urban environment division, Harris’s field of influence is more horizontal, with a nimble design team that operates across the City Council, unlocking areas of potential, where multiple departments need to be engaged and enthused – for example, in placemaking or sustainability. Harris is involved in the decommissioning and future use planning of the iconic Hanasaari Power Plant (built by leading modernist Finnish architect, Timo Penttilä, opened in 1960).

Says Harris: ‘It will require multiple stakeholders, so we wanted to make sure we have all relevant data before launching a design competition.’ Public consultations have been ongoing in the past year, with opportunities to explore the decommissioned areas. ‘We’re working with the city museum, discussing which aspects have to be preserved and modified. We’re looking at the financials, the cost estimates, what the building means locally. The decommissioning work will finish this summer. We’ll then move into the stage where there will be potential temporary use, both outdoor spaces and indoor. Some will be tested this autumn during our Flow music festival.’

Harris is also closely involved in the creation of a new combined design and architecture museum, to replace the two existing, separate museums that have outgrown their current buildings. There were five finalists to the initial design competition (out of a field of 600 entries). The winning scheme will be announced in September.

On top of steering projects of both national and regional importance, Harris’s job entails having to navigate political shifts with every four-year mayoral election cycle. It’s just as well she decided at a young age – and her father is an architect, so she had every encouragement down that route – that she’d like a role ‘more in the bigger picture of society and mediation and facilitation; bringing production and policy together.’

She completed an urban studies degree at what is now Aalto University, then spent time living in Paris and also Milan, before arriving in London in 2008, where she spent five years at the Finnish Institute, fostering dialogue between Finnish and UK design and cultural communities. She returned to Helsinki in 2013 to start a family and worked at Archinfo Finland, in charge of ‘architecture information promotion’, which included commissioning Finland’s pavilions for the Venice Architecture Biennales and ‘devising a national architecture policy for Finland. I got one approved for Helsinki.’

Has she ever experienced pushback or discrimination due to her gender? ‘Personally, I haven’t felt that. Or if there have been instances, I haven’t let them hinder what I’ve tried to do. But I have also been really fortunate in having mentors – clever, wise women – as my bosses, who have challenged me and given me space. I am really grateful for that. And I try to the best of my ability to give some of that spirit back to people who I work with.’